Are foreign affairs spokespeople and other Chinese diplomats creating bold social media posts outside official channels in Beijing or is it part of a grand plan?

In the summer of 2019, into her seventh year as a spokeswoman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), Hua Chunying was just about to finish four months of study at the Central Party School – the main training ground for senior Communist Party cadres.

The diplomat, then aged 49, wrote in an article for the school newspaper Study Times about the need for Beijing to get its message across online around the world.

“We must … enter overseas social media to give wings to China’s moral power and ensure that the Chinese discourse captures the moral high ground as soon as possible,” Hua wrote.

It was just days after Cui Tiankai, the Chinese ambassador to the United States, made his debut post on Twitter, a social media platform banned in China.

Ten days after the article was published, Hua was promoted to head the MFA’s information department, marking the start of an era of vocal Twitter activity for China’s diplomats.

In their attempts to tell China’s side of the story, these official Twitter accounts have regularly pushed the message of multilateralism. But they have sometimes taken an aggressive Wolf Warrior approach, a term that comes from a Chinese film of the same name depicting Chinese special forces fighting foreign mercenaries in Africa.

The tactic has attracted advocates at home and critics abroad, particularly in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic.

At about the same time as Hua took up her new position at the MFA, Zhao Lijian, a counsellor at the Chinese embassy in Pakistan announced his departure and bade farewell in several tweets.

As an active and outspoken Twitter user – then with more than 200,000 followers and now with 876,000 – Zhao was unusual among his colleagues, often posting or reposting dozens of tweets a day.

Zhao’s name soon appeared on the MFA website as one of Hua’s deputies, going on to become another ministry spokesman and continuing his bold tweeting style.

In the following months, more Chinese diplomatic accounts sprouted on Twitter, including the MFA official account @MFA_China and Hua’s @SpokespersonCHN.

Fast forward to 2020 and these accounts started to actively push Chinese voices into global discussions, a solid step towards the vision Hua presented in her article in 2019.

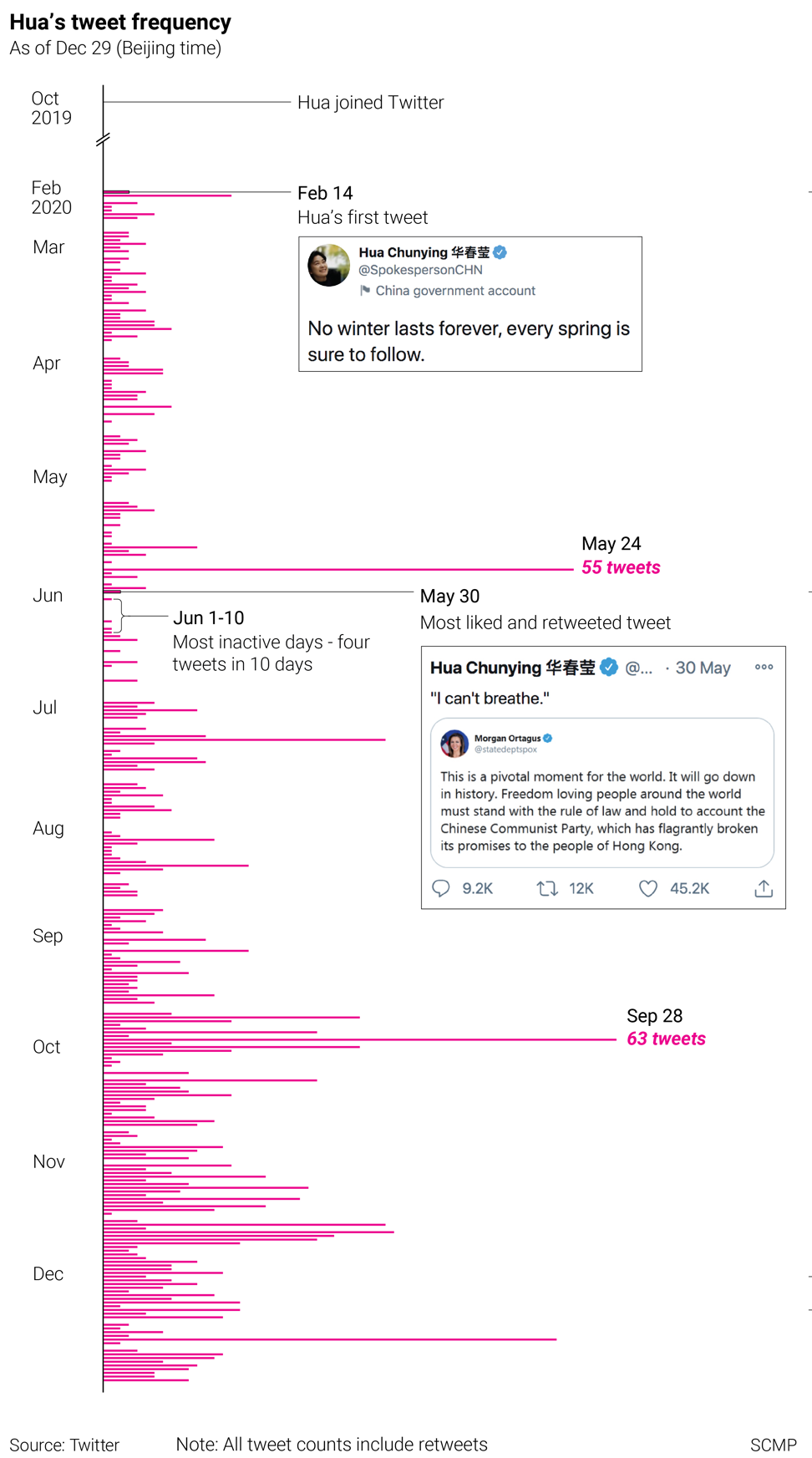

Hua’s first tweet was understated and came on February 14, at the height of the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, the city in central China enduring the first blow of the global pandemic.

“No winter lasts forever, every spring is sure to follow,” she tweeted.

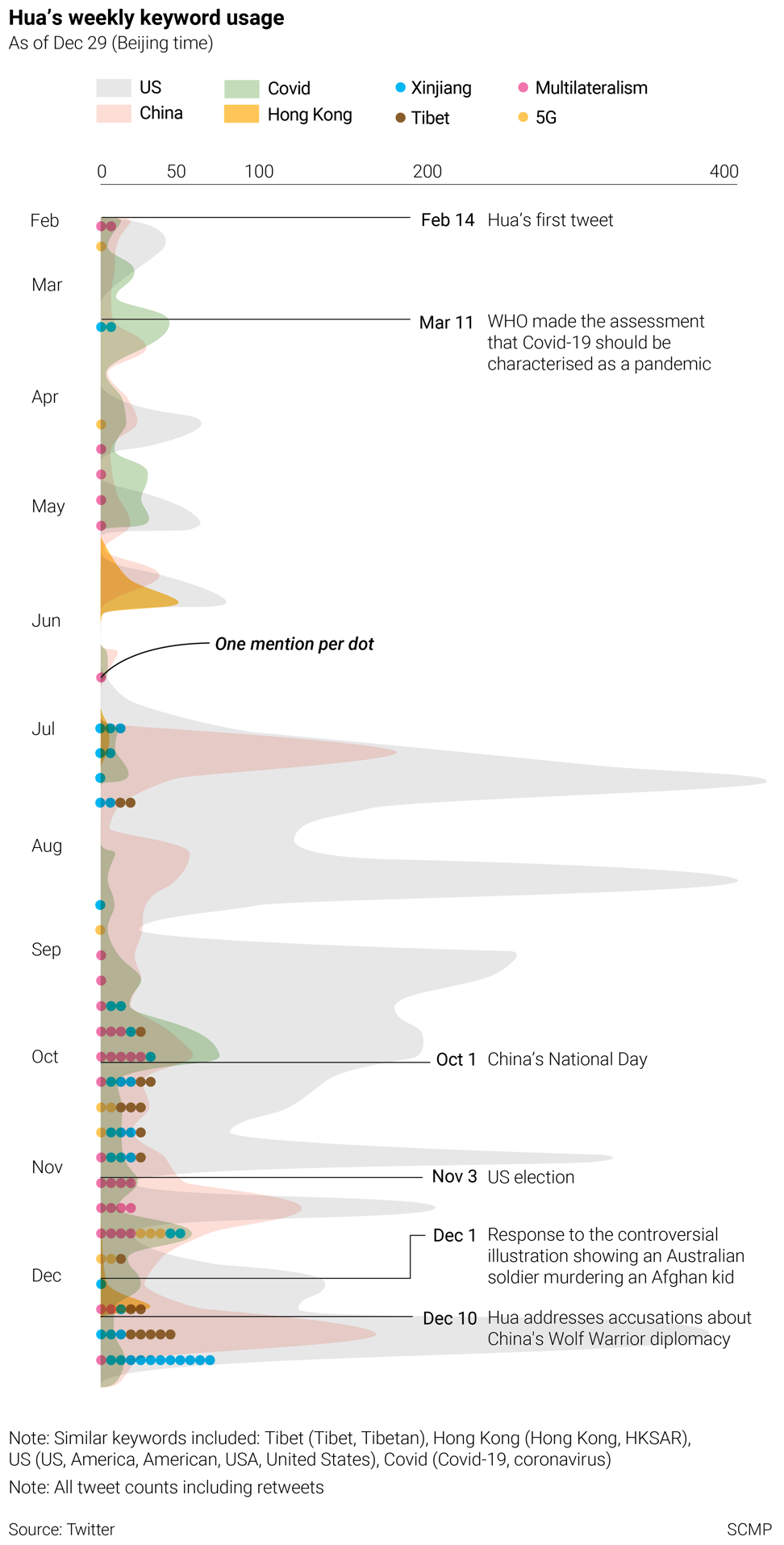

Many of Hua’s initial tweets expressed gratitude for help from abroad, but the geopolitical climate worsened drastically for China in March as the virus quickly spread beyond its borders.

China was soon the target of accusations that it initially covered up the outbreak and demands that it be held accountable. These voices were further amplified by social media, fuelling anti-China sentiment. The most vocal critic was US President Donald Trump, who called the coronavirus the “China virus”.

Allegations of human rights abuse in China’s northwest Xinjiang region and the passing of a national security law in Hong Kong in June further weighed on Chinese diplomats.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has quite altered geopolitics,” said Zhao Alexandre Huang, a visiting professor at Gustave Eiffel University in France. He has been studying the tweeting activities of Chinese officials’ accounts since 2017 when there were fewer than 10 active users, including diplomats and state media.

Now, the number has passed 200 and most of those were registered this year, Huang said.

“It was when the water was getting too muddy, there was no channel to do rational and constructive debate or conversation on social media,” Huang said.

While mostly acting defensively in response to attacks or calling for multilateralism, MFA spokespeople launched occasional wars of words to make the “water” even muddier. It was those tweets that made international headlines, and were seen as signalling Wolf Warrior diplomacy.

And on the front line of that attack was Zhao, Hua’s deputy.

On March 12, Zhao tweeted a conspiracy theory that the US military brought the coronavirus to Wuhan in October 2019. It came as US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo repeatedly labelled the virus as the “Wuhan virus” or “Chinese coronavirus”, and ignited a storm of accusations that Zhao was spreading misinformation.

Two months later, Hua was the one on the offensive. On May 30, two days after China’s top legislature, the National People’s Congress, decided to enact a national security law in Hong Kong, Hua wrote “I can’t breathe” in a tweet.

It was a reference to the death of 46-year-old black American George Floyd at the hands of police and was a response to US State Department spokeswoman Morgan Ortagus over her tweets saying the Chinese Communist Party eroded the freedom of Hong Kong people.

Where Zhao’s post attracted opposition, Hua’s tweet gained some support, being retweeted more than 8,700 times and gathering 45,200 likes.

Zhao set off another storm of protest in December when he posted a digital illustration of an Australian soldier holding a bloodied knife to the throat of a child in Afghanistan.

It sparked a furious outcry from Canberra, with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison demanding the removal of the tweet. Zhao refused and even pinned the post to the top on his account.

Nevertheless, it is still not clear whether these kinds of tweets are meant to be off-the-cuff opinions or part of a bigger strategy within the ministry. In March in an interview with American media outlets Axios and HBO, Cui, the Chinese ambassador to the US, distanced China’s official position from Zhao’s conspiracy tweet about the origin of the coronavirus.

Huang said the tweets were a result of one strategy within the MFA – the diplomats all convey the same messages and serve a common goal but do it with different styles.

But Ren Yi, an influential political blogger who writes under the name Chairman Rabbit in China, is not so sure, saying the Chinese diplomats’ use of Twitter might not be part of a rigid, centralised official tactic.

“Foreigners don’t really understand China. They tend to think everything coming from Chinese officials would be coherent. But in fact, these tweets contain many personal elements,” he said.

While the Wolf Warrior approach might not be winning hearts and minds overseas, it is popular at home.

Messages conveyed through tweets, especially conspicuous posts about China not being bullied by Western powers, are repackaged and republished with inflammatory language on domestic platforms by state-backed media, such as the nationalist tabloid the Global Times.

The content attracts mostly positive feedback behind the Great Firewall and fuels nationalistic sentiment.

Fang Kecheng, assistant professor at the school of journalism and communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), said the Wolf Warrior style was like a performance for the domestic audience and a way to show loyalty to the central leadership in Beijing.

“I don’t think it is effective in building China’s global image and reputation because it’s unnecessarily confrontational,” he said.

Huang from Gustave Eiffel University said diplomacy could be a channel to address domestic concerns.

“Diplomacy is the continuation of internal affairs. Nationalism is a key weapon for unifying thinking and defending the regime,” he said.

Most of the new MFA accounts have adopted a Trump-like tone since day one. Classic Trump phrases such as “fake news” can often be seen in the posts and all-cap tweets and exclamation marks are common.

Alessandra Cappelletti, an Italian scholar teaching international relations at Xian Jiaotong-Liverpool University, has been observing Chinese diplomats’ activities on Twitter.

She said their writing style was tuned to the tone coming from their American counterparts.

“I do not see any fundamental difference between Chinese and other countries’ diplomats,” Cappelletti said. “Western powers feel [they are] the only ones entitled to use social media for political communication, and as Chinese diplomats start using them as well they feel they are quickly lacking a reason to highlight how China is different and needs to be feared.”

Social media has fundamentally changed the way diplomacy works, in the same way it has changed other types of political communication: emotion often matters more than truth when trying to reach the broader public.

“The world perceives Chinese diplomats on Twitter as aggressive and vocal, but it is not because they indeed are,” Cappelletti said. “It is the platform of social media which requires more [assertiveness], otherwise the messages are not conveyed.”

Far from the spotlight and always hostile atmosphere in the MFA press conference room in Beijing, Chinese diplomats stationed overseas are a crucial part of the country’s Twitter public diplomacy network and not to be neglected.

Of the 152 Twitter accounts Hua follows, 126 belong to Chinese diplomatic figures stationed in different countries or international organisations. Most of them registered in 2019 and 2020, and frequently use local languages for tweeting.

Despite attracting less media attention, these accounts’ activities may better suit the mission of public diplomacy – communicating directly with the citizens of other countries and improving bilateral relationships.

“China‘s voice started to be heard,” Cappelletti said.