The resilience of Hong Kong’s housing prices is the result of low interest rates and masks its fundamental problem of a lack of affordable housing. Covid-19 stimulus money is inflating home values without providing a foundation for recovery.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic erupted in February, Hong Kong’s residential property sector has proved remarkably resilient, living up to its reputation as the Teflon market in periods of severe turmoil.

Despite an economy mired in what is expected to be its deepest recession on record, an unemployment rate that has shot up to its highest level in 15 years and concerns over the city’s future as Asia’s premier financial centre, house prices and sales have held up extremely well.

According to Savills, mass residential prices rose 3.5 per cent in the first three quarters of this year, while luxury property values dipped only 5 per cent. More tellingly, although sales in the mass market– homes below HK$10 million – fell 10 per cent, transactions at the top end of the mass market dropped just 5 per cent, with most of the decline coming in sales below HK$5 million.

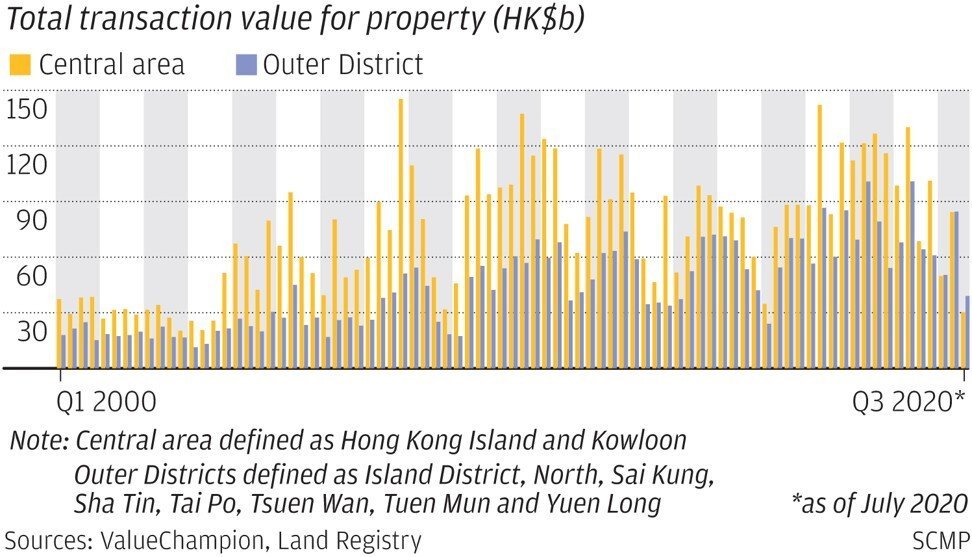

Commercial property, on the other hand, with the notable exception of the e-commerce-driven logistics sector, has been hit hard. Key gauges of performance in the office sector have plumbed new lows. In the third quarter of this year, net absorption of Grade A office space contracted by 633,000 sq ft, the lowest quarterly level on record, according to data from Cushman & Wakefield.

The decline in leasing activity has been sharpest in the Central district, where occupancy costs remain the highest in the world. Separate data from CBRE shows that the drop in demand in Greater Central (which includes the Admiralty and Sheung Wan districts) accounted for over two-thirds of the fall in net take-up last quarter. With Central’s vacancy rate at its highest level in 15 years, prime rents in the district are expected to drop by 25 per cent this year.

Yet, the diverging performance of Hong Kong’s residential and office sectors masks important structural factors which, when taken into account, paint a different picture of the underlying fundamentals of both markets.

The resilience of the residential sector stems partly from the virus-induced collapse in interest rates, which is reducing the downward pressure on house prices. However, these unprecedented, loose financial conditions are exacerbating deep-seated problems in Hong Kong’s housing market stemming from the chronic shortage of affordable homes.

The gush of cheap money – made even cheaper by the fact that the territory’s monetary policy is effectively set by the Federal Reserve through the currency peg to the United States dollar – is widening Hong Kong’s wealth gap by inflating home values and confining demand to a small number of high-income households.

A report published by JPMorgan last Thursday found that nearly 80 per cent of this year’s sales in the HK$5-10 million range or above were supported by 200,000 households making a monthly income of over HK$100,000. More tellingly, most of these households took advantage of the ultra-low interest rate environment to buy their second or third home for investment purposes under different family names.

Cusson Leung, head of Asia property research at JPMorgan and the author of the report, estimates that the 200,000 high-earning households can comfortably absorb the annual supply of 20,000 to 22,000 units in the private market. “It doesn’t matter how much supply there is as it’s catering almost entirely to investment demand,” notes Leung.

This shows that the resilience of Hong Kong’s residential market comes at a hefty price. Not only is the sector becoming more detached from economic reality – the market remained firmly in bubble territory, according to UBS’ real estate bubble index published last month – it lacks a vital shock absorber at a perilous time for the city’s economy and politics.

The office market, however, while having suffered a severe blow due to the pandemic-induced hit to corporate performance, is more in sync with economic conditions. As I argued previously, Central’s exorbitant rents and unnaturally low vacancy rate made Hong Kong an outlier among the world’s leading office markets. A correction was long overdue, and is now guaranteed to be a meaningful one.

Although the plunge in rents is happening for the wrong reasons – a dramatic drop in demand, exacerbated by a global public health emergency – it is a crucial safety valve that is laying the groundwork for a healthier and more competitive leasing market. Occupiers, who previously had few options to expand or upgrade their office requirements, now have more of an incentive to relocate within the city’s central business district.

Furthermore, the recession is accentuating the importance of Hong Kong’s mature decentralised office market. Not only are Hong Kong East’s rents still only half those in Central, newer and high-specification buildings across the city’s non-core districts support a flight to quality. Improvements in infrastructure and advances in technology encourage occupiers to relocate to decentralised districts. “Central’s spell was broken some time ago,” notes Simon Smith, head of research for Asia-Pacific at Savills in Hong Kong.

The residential market may be holding up well, but it is the city’s office market that is having a better crisis as cheaper rents and greater choice for occupiers lay the foundations for a stronger and more sustainable recovery.