In mid-2018, just as Donald Trump was launching his first broadsides in a trade war against China, I arrived in Beijing on a semiregular trip to try to grasp how the country's political establishment saw the U.S. president.

That May, Trump had announced tens of billions of dollars of tariffs on Chinese goods. Soon after, with Beijing still scrambling to respond, the U.S. president announced a fresh set of import taxes.

In public, Beijing responded robustly in kind, with the Commerce Ministry announcing matching tariffs on U.S. imports and declaring that China was "absolutely not afraid of a trade war."

In China's powerful ministries and prestigious think tanks, I had fully expected the elite disdain for Trump and his hardball tactics that prevailed in Washington would be mirrored in Beijing.

But rather than scorn, the opposite turned out to be the case. To my surprise, the officials and scholars either feared or admired the U.S. president. Whereas his critics in the West found nothing but cynicism and chaos in the president, many officials and scholars in China saw strategic calculation and tactical genius.

For all their public bluster, the Chinese in private struck a less confident tone, seemingly thrown off balance by the double whammy of tariffs and Trump's untethered, confrontational tactics.

The usually confident bureaucrats and scholars, who in the past had generally dismissed the latest broadside from the U.S. with a kind of this-too-will-pass shrug, seemed confused and occasionally fearful.

In multiple conversations, the officials and scholars were desperate for insights into how to handle Trump and game out his next move. Naturally, I had little to offer them on this count. I told them that if Trump's closest advisers had no idea what he might do next, then nor did anyone else.

The growing band of critics inside China of President Xi Jinping's increasingly illiberal rule were transfixed for different reasons, gleeful at how the U.S. president, more than any of his predecessors, had been able to rattle the Chinese leadership.

Today, the businessman-turned-politician has become widely viewed as an accelerant of American decline, capped off by the abysmal response to COVID-19. It is clear that the U.S. is weaker, and China stronger, as his four-year term draws to a close.

But the chaos of the past few months, culminating in the Sept. 26 COVID-19 superspreader event at the White House, is overshadowing an examination of the once-in-a-generation overhaul of U.S.-China policy that he has presided over.

Even less well-appreciated is that many allies in the region welcome the change in policy, if not the manner of its execution.

In Washington, getting tough on China has become one of the few bipartisan positions in an otherwise deeply divided polity. Should Joe Biden win the presidency, the contest between the U.S. and China across multiple domains, on everything from trade to technology, is set to endure -- and, in all likelihood, intensify.

"The debate has shifted from why a new approach is needed," said Charles Edel, a State Department official in the Obama administration. "Now, the question is what that new approach should be, and how it should best put into effect."

The end of the first term may also be obscuring the valuable practical lessons the Trump era offers, on how the U.S. can push back against China to check the relentless upending of the status quo that it has successfully pursued since the 1990s.

The episode with tariffs in mid-2018 represented a moment when Trump, ever so briefly, was a symbol -- in China, at least -- of something the world used to be very familiar with: a powerful America with the ability to dictate terms to rivals.

Mark Leonard, the British commentator, another visitor to Beijing in mid-2018, wrote in The Financial Times around this time that the Chinese described Trump as a "master tactician, focusing on one issue at a time, and extracting as many concessions as he can.

"But they also see him as a strategist, willing to declare a truce in each area when there are no more concessions to be had, and then start again with a new front."

Trump's ability to frame issues to his --- and America's -- advantage in foreign policy has won begrudging praise from one of Hillary Clinton's and now Joe Biden's senior foreign policy advisers, Jake Sullivan.

"I do think that Trump shaking things up to a certain extent in terms of [how] he described and framed certain issues relating to American foreign policy created more space for a serious reckoning that was long overdue," Sullivan said in a recent Lowy Institute podcast. Trump was particularly skillful in connecting the economic suffering of the American middle class with global trade and the rise of China.

Trump's confrontational tactics were quietly welcomed in Japan, too, although more so on national security issues than trade. Among Trump's fans were then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's foreign policy advisers, who had often despaired about former U.S. President Barack Obama's more collegial approach. Obama, for example, reined in the Department of Defense when some of his top military advisers wanted to push back more strongly against Beijing's island-building in the South China Sea.

An anonymous senior Japanese official, writing in The American Interest magazine this year, acknowledged the shortcomings of Trump's China and Asia policy.

"But if you ask [Japanese policymakers] if they miss the Obama presidency, most of the same people would also respond negatively -- perhaps more so," the official, who has yet to be unmasked, wrote.

"For countries on the receiving end of Chinese coercion, a tougher U.S. line on China is more important than any other aspect of U.S. policy.

"Asian elites, in Taipei, Manila, Hanoi, and New Delhi, increasingly calculate that Trump's unpredictable and transactional approach is a lesser evil compared to the danger of the United States going back to cajoling China to be a 'responsible stakeholder.'"

The article did not win universal endorsement in Japan and the U.S. In the case of Japan, Obama's advisers pointed out, correctly, that Washington had given Tokyo everything it asked under his presidency, including a U.S. pledge to defend the Senkaku Islands, which are claimed by China.

"The reality is that Obama's stance toughened through the course of his two terms -- he started out much more open to engagement, but became jaundiced as time went on," said Toshihiro Nakayama, professor of American politics at Tokyo's Keio University, in reply to the anonymous article. "Had Hillary Clinton won, U.S. policy would have been as tough, or even tougher, than the one that has taken shape under the Trump administration."

Obama's advisers acknowledge privately, however, that Trump has provided a reminder of just how powerful the U.S. can be when it decides to throw its weight around -- something they were loath to do.

Trump had his supporters in Australia as well. In part, this was ideological, as the conservative government in Canberra was more naturally aligned with Republicans in Washington.

But Trump's harsh rhetoric was often encouraging at a moment when Australian policy towards China had taken a hard turn, leaving Canberra feeling isolated and exposed to Beijing's reprisals.

Occasionally, the Trump administration has eschewed the pretense of strategy and used brute force to get its way diplomatically on China, with significant results. U.S. sanctions on Huawei Technologies are a case in point.

A year ago, Washington's campaign to stop countries around the world, particularly developed nations, from adopting the Chinese telecommunications giant's standard for 5G services seemed to be failing.

The U.S. was even struggling to convince the U.K., Washington's closest and longest-standing intelligence partner, to agree to push Huawei out of its preeminent position in the U.K. telecommunications network.

Months later, the full-throated campaign led by Mike Pompeo, the U.S. secretary of state, has borne fruit. The U.K. has come on board, as has much of Europe -- though not yet Germany. Japan, Australia, Canada, Singapore and New Zealand, among other countries, have all chosen non-Huawei providers.

The Huawei campaign, then, was a reminder of how formidable American power remains, even at a moment of relative decline. The pressure on the Chinese company has been intensified by Trump's restrictions on sales of technology to it.

Still, whatever praise Trump's critics might have had for the president's ability to build leverage with China, they are disparaging about the way he squandered it. In Jake Sullivan's words, while there was merit in Trump's diagnosis about America's foreign policy, his prescriptions for a cure have failed.

This is the key critique of Trump on China. Trump has sown chaos at home and abroad, leaving him little ability to execute any sustained strategy in either place, if there ever was one. Trump has relentlessly attacked South Korea over the cost of troops in the country, for example, and threatened both Seoul and Tokyo, two allies, with tariffs on automobiles. He also alienated many in Europe, especially Germany, through constant disparagement of Nato, the European Union, and the continent generally.

"Trump masquerades hostility as strategy," Robert Zoellick, the former World Bank chief who served in Republican administrations, wrote in The Washington Post in October.

In the case of the tariffs, for example, Trump's initial action put Beijing off balance. But the limited trade deal that followed addressed none of the core complaints about China's behavior in Washington.

Many government officials in the U.S. who served Trump and backed the hardening of China policy agree with this critique. Notable hawk John Bolton, who served as national security adviser, recounted in his memoirs how Trump had backed China's detention of Uighurs in meetings with Xi Jinping and asked the Communist Party leader for support in his reelection campaign. (Other Trump officials denied hearing these comments.)

In other words, Trump's own deep personal flaws -- his susceptibility to flattery, a predilection for dictators, and utter absence of principle -- consistently undermined his public policy positions and broader U.S. interests.

Trump has presided over, and indeed, encouraged, a corruption of American institutions, putting them at his own political service. Anyone, be they a Democrat, Republican or a nonpartisan civil servant, has been punished if they stray from his self-serving, self-aggrandizing diktats.

On top of that, Trump has recklessly presided over an atrophying of the U.S. government. Beijing, by contrast, has assiduously amassed enormous state capacity which it expends in a disciplined, if brutal, fashion.

COVID-19 has been a telling episode in this respect, for both political systems.

In China, the Communist Party mishandled the outbreak, punishing doctors and journalists who sought to sound the alarm about its spread in Wuhan in December and January.

But once the central authorities acted, the various levels of government were able to apply their unchecked powers to rein in the virus. China's economy is bouncing back as a result.

In the U.S., Trump either lied to or misled the public about the pandemic, swung between praising Xi and blaming him for the virus, and then used the issue to attack political opponents.

As a result, in the end, COVID-19 simply became another battleground in the nonstop, never-ending partisan cultural wars in the U.S., draining the American political system of further capacity, at home and abroad, and at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives.

The most conspicuous area of Trump's failure on China has been in the area he has mostly focused on, trade -- at least, according to the benchmarks he set himself when he came to office.

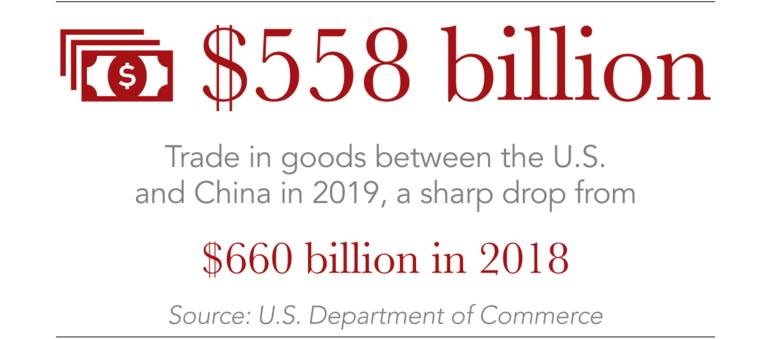

American's bilateral trade deficit with China when Trump came to office in 2016 was about the same as in 2019, at $345 billion. China's exports are continuing to rise, even in the wake of the pandemic, outpacing the increase in U.S. sales abroad.

The one significant trade deal he signed with China, inked in early 2020, has fallen well short of its targets. So far, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, China's purchases of U.S. goods they promised to make this year are running at about one third of their commitments. The pandemic is partly to blame, but there is a substantial shortfall nonetheless.

The tariffs themselves have been costly for American consumers along the way, amounting to "one of the largest tax increases in decades," in the words of the nonpartisan Tax Foundation in a 2019 report.

Trump repeatedly said that the tariffs were being paid by China, whereas, in fact, most were paid by consumers at the checkout in the form of higher prices.

Farm subsidies, used by Trump to cushion the impact of China's retaliatory tariffs against U.S. grain and food exports, have also been expensive. They reached a record $37 billion in 2020 -- more than the Agriculture Department's entire discretionary budget.

Whatever gains Trump might have made, in other words, they have been overwhelmed by the political and financial costs of obtaining them.

Seen through this lens, Trump's China trade policy, at the end of the day, is much like the line from Shakespeare's "Macbeth": "It is a tale, told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing."

Ryan Hass, who served on the National Security Council in the Obama administration, put it more diplomatically in a paper for the Penn Project on The Future of US-China Relations, in arguing that Trump's confrontational China policy has delivered few gains.

"Areas of confrontation [with China] have intensified, areas of cooperation have vanished and the capacity of both countries to ... manage competing interests has atrophied," he said.

On trade, Hass said the deal "left untouched the Chinese behavior that precipitated the trade war to begin with."

"U.S. negotiators settled instead for a series of pledges of policy reforms Beijing had already decided to take and a set of purchasing targets of American products that China will not meet."

Any judgment of Trump's China legacy, and the challenge facing a potential successor, must take into account Beijing's own behavior, along with the rise of Xi Jinping as a global political force.

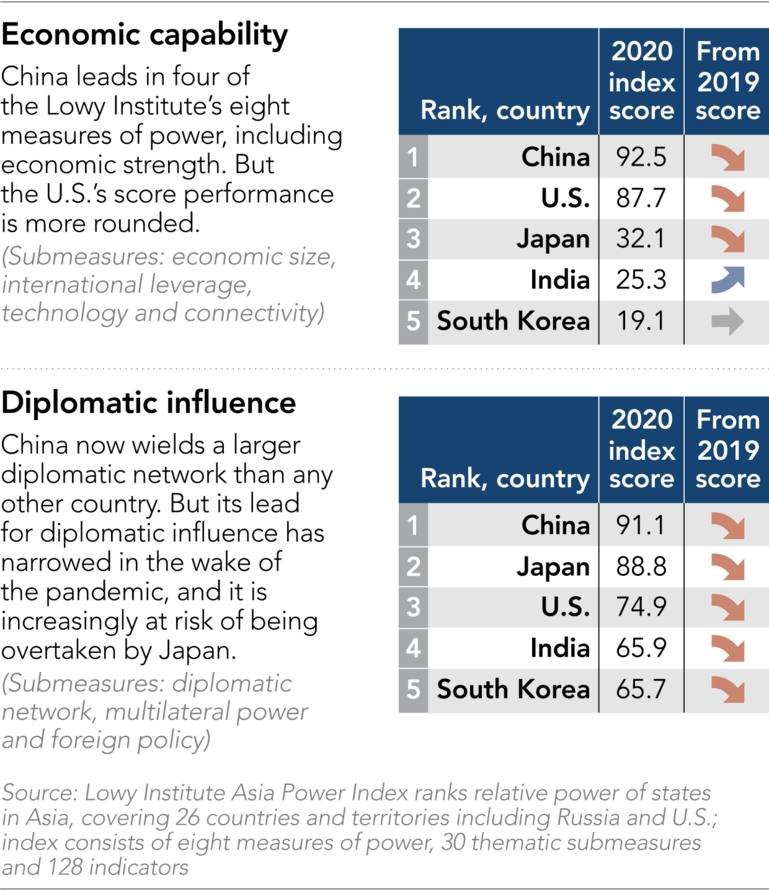

America's status may have plummeted under Trump, but China's position has not risen in tandem with this fall, even though Beijing had substantial opportunities to advance its global position.

Beijing's "wolf warrior" diplomacy has brought into the open the kind of aggressive Chinese positioning that has long been a feature of closed-door interactions with the country's diplomats.

China's growing economic and military power, and Xi's own forcefulness, has emboldened Beijing to push harder on many fronts, including in Taiwan and in the South China Sea.

"The Chinese do have an aspiration for great power status by virtually every measure of comprehensive or composite national power that you can measure," said Chad Sbragia, a deputy assistant secretary of defense, in September, following the release of the Pentagon's annual report on the Chinese military.

But COVID-19 has shown how Chinese diplomacy has seemingly unlimited capacity to alienate not just the developed world, but potential partners in the region as well.

China's aggressive cover-up of the origins of COVID-19 and its ferocious reaction to any criticism on that front has been a disaster, as was the heavy-handed "mask diplomacy" which followed.

China is now attempting something of a diplomatic recovery, with a focus on Southeast Asia. Beijing has already promised Indonesia, the region's most populous nation after China, that it will be one of the first to get a vaccine when one is available.

Beijing's job, though, for all their missteps, has been made easier by the political upheaval in Trump's America and the subsequent lack of bandwidth in Washington for sustained diplomacy.

"Containing Chinese global influence, if that is the Trump objective, will require more than threats, tariffs and sanctions," said Isabel Hilton, the British columnist and author, in an exchange on the Asia Society's China File.

"It will require the U.S. to regain its power of attraction both for citizens of hostile states and those of its traditional allies."

Worried about a U.S. retreat, its allies in the region have stepped up. China's most consistent competitor in Asia in recent years has been Japan, and, in the Pacific, Australia.

Unsurprisingly, Chinese officials and scholars increasingly take the view that the Trump era symbolizes an America that is in secular decline.

In the words of Wu Xinbo of Fudan University, one of China's leading public intellectuals, U.S. global leadership is "shrinking" and ceding ground to other nations. "The U.S. is exhausted, and unable to carry the world," he wrote in 2019.

A second term for Trump would almost certainly offer more of the same: constant political infighting at home and inconsistent, capricious diplomacy abroad.

Aside from the occasional piece of effective statecraft, Trump 2.0 will continue to drain America's soft power reserves, and doubtless embolden Beijing around the world.

In the event of a Joe Biden victory, there is no magic bullet to reset America's standing in Asia. For starters, like Barack Obama in 2009, Biden would be inheriting an economic crisis. His first year in office would inevitably focus on that.

More importantly, few in the U.S. seem to be looking for an off-ramp in the contest with China. Rather, the prevailing sentiment is that the U.S. is late to the game of strategic competition with Beijing, and is playing catch-up.

The U.S.'s allies in the region will also be looking with anxiety toward any appointments to senior diplomatic positions in any Biden administration.

Their concerns include Biden himself. Despite years as a senator on the Foreign Relations Committee, Biden's positions can be quixotic, unpredictable and highly personalized. Robert Gates, Pentagon Chief under both George W. Bush and Barack Obama, famously said in his memoirs that Biden had "been wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades."

During the Obama administration, Tokyo, at different times, was highly critical of both Biden and Susan Rice, the former national security adviser, who is in line for a senior job should Trump be defeated.

Both Biden and Rice, at one point, embraced Beijing's concept of a new era in "great-power relations," which Tokyo saw as a kind of "G-2" concept which would exclude allies like them in favor of U.S.-China deal-making.

The Obama administration eventually shunned the idea when they realized that Beijing was telling other countries in the region to butt out of contentious issues because they would be solved in tandem with the U.S.

Biden's potential advisers range widely in their views, from national security hawks to multilateralists who will want to focus on cooperation on issues like climate change and fighting pandemics.

Trump has killed a number of multilateral agreements. He withdrew from the 2015 Paris climate accord, ditched the 2015 Iran nuclear deal and pulled the U.S. out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Biden is likely to reverse all three decisions, though getting the U.S. back into the TPP (now called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership) will take work.

The U.S. Congress and the remaining members of the pact would both have to agree. China itself is now discussing whether it should try to join. Another regional agreement -- which China is a part of, but the U.S. is not -- the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), could be signed in November.

Ultimately, political style aside, Trump may prove to be prophetic in his questioning Washington's postwar role in Asia. After all, he was elected on a platform of "America First," a popular slogan.

Put another way, at a moment when, more than ever, countries in the region want the U.S. to play a balancing role against China, America itself, or at least American voters, may be less interested than ever.

As Australian China scholar John Fitzgerald noted: "Neither China under Xi Jinping nor the U.S. under Donald Trump is committed to upholding the old order." Where, he asked, does that leave the rest of us?