Business owners struggling to survive as supply has outstripped demand, and some are selling other health products or focusing on design.

Nearly a year since Hong Kong came under the spectre of the coronavirus, local mask manufacturers, who jumped on the supply bandwagon at the start of the pandemic amid a frenzied demand for the protective gear, are now facing a reversal in fortunes.

Factory owner Denis Huen Yin-fan has suffered losses for three consecutive months to November, and is laying off workers. Huen, 33, estimated his company masHker lost about HK$10,000 (US$1,290)to HK$20,000 each month in that period on average, and the drop in orders had forced him to cut his team of 30 staff by more than half.

When he launched the brand he co-founded in March last year, 20,000 pre-order slots were snapped up in 10 seconds. That has dwindled to just about 500 to 1,000 orders a month.

“We didn’t expect that many people would suddenly start mask factories too, and didn’t think the market would have changed so fast,” he said.

While some factories operate with government subsidies, many privately owned mask companies which run on their own resources now have to either reinvent their businesses or risk going under.

Simon Chan Kwok-hei, chairman at Hong Kong Mask and PPE Association, forecast a third of the city’s mask factories could go bust in the first quarter of 2021.

He estimated there were more than 200 factories currently, producing 208 million masks a month at least.

“Now, it’s very hard to operate. Many mask factories cannot sustain this any more,” Chan said. “I estimate that in the next three months, one-third of factories will face big operational hurdles or even have to shut down.”

He said the severe mask shortages that once rocked the city had already eased by last summer, with locally made and imported masks from mainland China and other countries flooding the market.

The production cost of made-in-Hong Kong masks was more than HK$1 per item, far more expensive than just dozen cents on the mainland, he added.

In the case of masHker, Huen said the company operated as a social enterprise and hired disabled residents such as those with down syndrome, as well as those undergoing rehabilitation even though it had to bear a higher operating cost.

“But the customers don’t look at this. They just compare prices,” he said. “The concept we adopted was actually killing ourselves.”

After spending millions of dollars and scrambling for raw materials and machines for months at the beginning of 2020, local mask makers are fighting another wave of challenges arising from market oversupply, particularly competition from mainland rivals.

To survive, some brands have churned out new designs with special patterns to boost sales, with some rolling out physical stores and health care products. Others have succumbed and sold their production lines to interested businessmen.

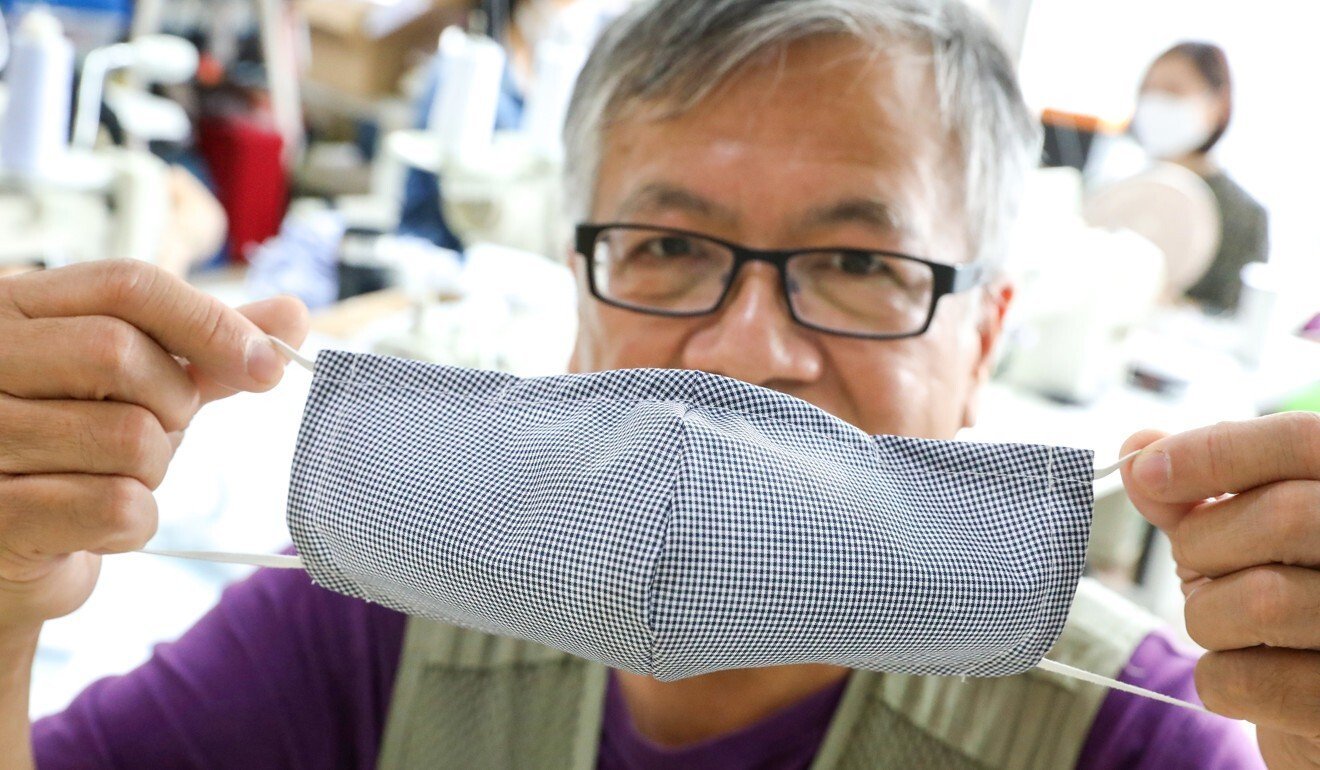

To stay afloat, Huen is also transforming his business to produce colourful masks as fashion products, seeking corporate clients to help brands produce the protective wear, and exploring more export opportunities.

“We can’t just simply make masks. We have to find other paths,” he said.

Facing fierce competition, another operator, Mask Factory’s co-founder Tong Ka-fai, noted the surplus started last autumn, with fewer people subscribing to their services.

His factory’s monthly production volumes fell from 10 million between March and November to around 7 million masks currently.

But Tong said local manufacturers should not compete with their rivals over production volumes. “We should focus on the gimmick and design,” he said.

While the production volumes of plainly coloured masks slumped, he noted the figures for those with fashionable designs were growing.

Tong’s retail shop in Tsim Sha Tsui touts mask patterns such as dots and trees, and has received overwhelming support from customers, with long queues often seen on weekends.

The company also started selling health products such as Covid-19 antigen test kits and tumblers with LED disinfection functions installed to prepare for the day when masks will no longer be as widely sought.

Its website will add a function allowing customers to book a doctor’s appointment, in a bid to shore up brand loyalty.

“No businesses will last forever, they will all have to transform one day,” he said.

For another factory masklab, the strategy to sell masks with special designs propelled month-on-month sales despite the demand for its original blue masks falling to “pretty much zero” – from millions of dollars about seven months ago.

“Every time we launched a new product, sales would grow, but then this would drop fairly quickly again. The whole market became about having to keep releasing new design and products,” co-founder Albert Chen, 33, said.

He found customers had grown to use masks to express their personal style and match their clothes, adding his physical stores that pioneered the way for customers to pick individual mask designs contributed to their success.

With vaccines expected to arrive in the city this year, Chen appeared unbothered. He said his company had initially expected the pandemic would last until the end of 2020, so his business plans were in line with such anticipation, with short-term leases signed for the stores.

“We are not making more capital expenditure in Hong Kong,” Chen said. “The plan now is to just slowly close down the stores.”

He predicted people would still wear masks for the next couple of years, even with vaccines, and his firm would keep mask production small enough to fulfil that niche market.

In the long run, Kenneth Kwong Si-san, a former chemistry lecturer with Chinese University who often advised various mask manufacturers on their operations, said Hong Kong mask makers must export their products because mainland companies could offer cheaper items.

“Hong Kong residents are realistic,” Kwong said. “Also, although many mainland products are of poor quality, not many locals know the distinction.”

Mainland businesses were already copying the design of colourful masks in the city, he added.

Kwong said he knew of four to five factories having already sold their production lines after suffering great losses. Asked whether such buyers still found the business profitable, Kwong replied: “They are just ignorant, really.”

The 20 production lines that received a total of HK$14.6 million in government subsidies under a scheme to support local mask production tended to be in a more secure situation as officials had committed to procuring up to 2 million masks from them monthly for a year.

“There is currently an abundant supply of masks in the retail market, and the policy objective of the scheme has been achieved,” said a spokeswoman from the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau.

She said local mask production should operate in accordance with commercial and market principles, adding that the government had no plans to inject further funds into the scheme.

But Chan, the association chairman, said he hoped authorities would set up laws to regulate the quality of masks and boost the sales of local manufacturers who were not part of the scheme, adding that developing an industry trademark for good standard would be helpful.