A decision on the legality of French President Emmanuel Macron's pension reforms is imminent. Here Sky News explains what the changes are and why they have triggered mass strikes across the country.

A ruling on the legality of Emmanuel Macron's controversial pension reforms is expected today after nationwide protests and strikes continued on Thursday.

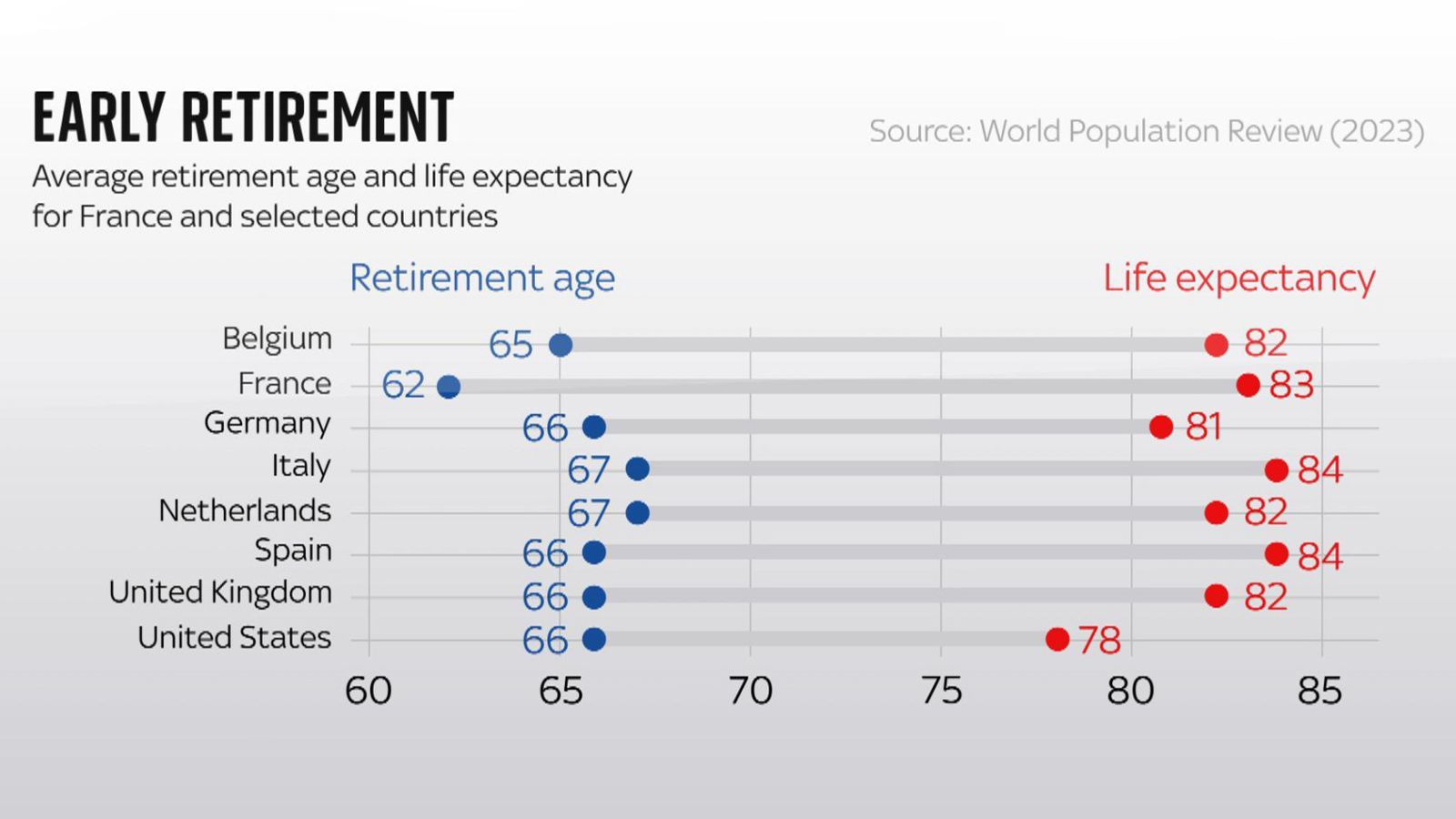

The president's bid to increase the state pension age from 62 to 64 is facing its final test from the Constitutional Council.

Rubbish collectors and transport workers were on strike in Paris yesterday, while river traffic was blocked on the Rhine river.

France has seen widespread protests after the government invoked Article 49.3 to push the changes through without a vote by MPs last month.

Here, Sky News explains why the reforms have sparked demonstrations and looks at how France's situation compares to other European countries, including the UK.

SNCF transport workers in central Paris on Thursday

SNCF transport workers in central Paris on Thursday

What is the retirement age in France - and how is it changing?

France's state retirement age is 62 - much lower than many of its European neighbours. In the UK it's 66, Germany and Italy 67, and Spain 65.

French workers can receive a state pension from the age of 62, but it will be less if that person has not made the required number of contributions.

Aged 67, they are entitled to the full state pension regardless of their contributions.

Mr Macron's changes will see the age that workers can receive a state pension increase to 64.

This will be done gradually by three months a year from September 2023 until September 2030.

The number of years someone will have to make contributions to get the full state pension will increase from 42 to 43 in 2027.

What is Article 49.3 and why did Macron use it?

Article 49.3 is a part of the French constitution that enables a government to pass a law without a vote by MPs in the National Assembly.

It was introduced by Charles de Gaulle in 1958 to bring about greater political stability and expand government powers.

It has been used more than 80 times since its inception, most notably by former socialist prime minister Michel Rocard 28 times between 1988 and 1991 under then president Francois Mitterrand.

Mr Macron's former prime minister Edouard Philippe tried to use it for pension reform in March 2020 but failed when the COVID pandemic broke out.

The French president's current PM, Elisabeth Borne, announced the proposed pension changes on 10 January.

Just minutes before they were due to be voted on in the National Assembly in March, she announced they would be forced through with Article 49.3 instead, causing outrage.

This is because her party, and Mr Macron's - En Marche - lost its absolute majority at last year's election and they had no guarantee of getting it through, despite it passing in the Senate.

The 2020 bid to change the pension system had already failed and resulted in the longest strikes in French history.

What is Macron's argument?

France's generous welfare state has long weighed heavily on the economy and workforce.

In the third quarter of 2022, national debt stood at 113.4% of GDP - more than in the UK (100.2%), Germany (66.6%), and similar to struggling economies like Spain (115.6%) and Portugal (120.1%).

It also means the workforce is shrinking. There are only 1.7 workers for every pensioner in France, down from 2.1 in 2000.

"This is Macron's flagship policy," David S Bell, emeritus professor of French government and politics at the University of Leeds, tells Sky News.

"He wants to push it through before he steps down at the end of this term.

"But the problem isn't an immediate crisis - it's a future burden based on economic projections. It's the opposite to the way politics works, which is to focus on the immediate, headline-grabbing issues.

"His argument is that unless these reforms are made, and the French working life is made longer, the country won't be able to afford it."

Addressing strikes on French TV, Mr Macron argued: "This reform isn't a luxury, it's not a pleasure, it's a necessity. The longer we wait, the more [the deficit] will deteriorate."

'Heated and passionate' issue

France has enjoyed a lower-than-average retirement age since the Mitterrand presidency in the 1980s, when it was brought down to 60.

Since then, along with favourable unemployment benefits and the 35-hour working week, it has become a staunchly defended "right" in the eyes of the public.

Demonstrators rally against pension changes on the Place de la Concorde in Paris

Demonstrators rally against pension changes on the Place de la Concorde in Paris

Prof Bell says: "The expectations of the French state are different to the ones in the UK.

"It's expected that the state has certain functions and duties and pulling the rug out from under that, has seen people asking. 'Well, why do that?'"

There is also a degree of doubt over the reliability of economic forecasts, he adds.

For years, politicians have tried and failed to get pension reform through in the hope of improving public finances.

In 1995, Jacques Chirac faced mass strikes and was ultimately unsuccessful. His successor Nicolas Sarkozy succeeded in increasing retirement age from 60 to 62 in 2010, but faced a huge backlash.

French commentator Agnes Poirier says: "The French are very fortunate and probably don't realise how fortunate they are.

"This would just put France closer into line with its European neighbours.

"But pension reform is a very heated and passionate topic in France, probably because most people here - apart from the very, very rich - rely on state pensions.

"There is no such thing as the individual private schemes you get in the UK or the US."

What happens now?

When the government invokes Article 49.3, MPs can trigger a vote of no confidence. Two motions were tabled - but neither passed.

Only 278 MPs, mainly from the left and far right of French politics, voted for the first, falling just short of the 287 needed to bring down the government. The second from Marine Le Pen's far-right National Rally party also failed.

In his TV address, Mr Macron said the reforms would have to be adopted "by the end of the year".

Their final test will be on Friday when they are put before the Constitutional Council.

The council is made up of nine people - three appointed by the president, three by the head of the National Assembly (lower house of parliament), and three by the head of the Senate (upper house of parliament).

Largely former lawyers, business people, senior civil servants and ex-politicians, they oversee the final stage of approving any new law - and consider whether it adheres to the constitution.

Although they can block it, this is very rare, with government sources claiming it will be given the green light.

There is one final mechanism unions can use to stop the bill going through - a referendum - but for this they would have to get the approval of both the council and 10% of voters within the next nine months.

It has not been successfully used since it was introduced in 2015.

If the council approves the pension reforms, the government could formally adopt them in the coming days.

The government hopes this would bring an end to nationwide protests.

But there is no guarantee the disruption will end.