Many top culinary masters are abandoning the French capital in favour of greener pastures, where they can have a hand not just in choosing, but in growing their ingredients.

It began before the pandemic: an exodus of chefs abandoning Paris for the French countryside.

James Henry's 2017 departure was perhaps the most publicised. The Australian chef, who first skyrocketed to fame at small-plates trendsetters Au Passage and the former Bones, left the Parisian cityscape to work alongside chef Shaun Kelly (ex-Au Passage) on a passion project: opening a restaurant and inn in the small town of Saint-Vrain 30km south of Paris. The result – Le Doyenné – is set to debut later this year. And, as the pair plant their orchard and renovate the 19th-Century greenhouse and stables, they've also been supplying some of Paris' top restaurants with produce from their three-acre vegetable garden.

But Henry and Kelly are far from the only chefs to step out of Paris in recent years.

"I think it started before Covid, but it was discreet," said Daniela Lavadenz, owner of Le Saint-Sébastien restaurant in Paris' trendy 11th arrondissement. "There was already an explosion of people buying country homes before Covid. But everything was multiplied with the pandemic."

To wit: chef Sven Chartier of the former Michelin-starred Saturne left the capital in late 2020 for the countryside of the Perche region, 150km west of Paris; his new néo-bistrot, Oiseau Oiseau, opened in October 2021 boasting a menu brimming with local produce. In 2018, former jewellery shop owner Mickaëlle Chabat and her husband, chef Louis-Philippe Riel (ex-Le 6 Paul Bert), ventured even further afield to the Italian border for a new home by the slopes. They found the house that would become their Auberge de la Roche in the town of Valdeblore (whose Alpine ski resort La Colmiane boasts the longest zip line in France) and launched the project in collaboration with chef Alexis Bijaoui, formerly of Paris' Garance.

Tapping into local terroir is at the heart of Auberge de la Roche

Tapping into local terroir is at the heart of Auberge de la Roche

"We fell in love with the view," said Chabat. "It's almost like being in the middle of nowhere."

The preponderance of chefs abandoning the capital in favour of greener pastures is, in part, a reflection of an ever-growing interest in locavorism. Despite a few anomalies – such as mushrooms grown in the Catacombs and wine produced in a handful of public parks – Paris has long been known for transforming ingredients, rather than producing them. But in recent decades, many Parisian chefs had been paying considerably less attention to where those ingredients were coming from.

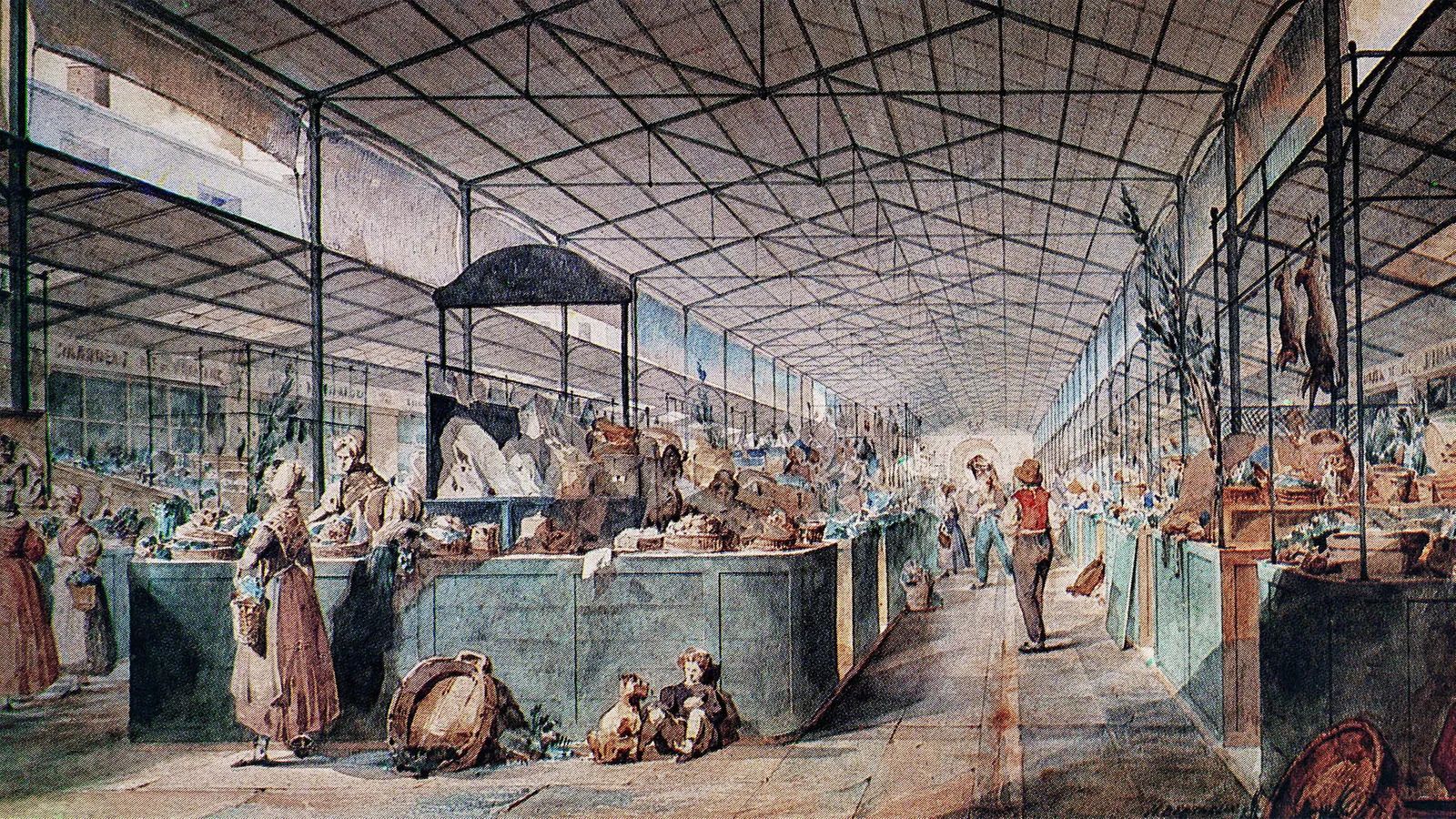

Farmers' markets selling local produce are thin on the ground in Paris, with most of the city's marchés actually peddling produce from Spain, Italy and Portugal by way of wholesalers. The central Les Halles market, a mainstay of Paris since the Middle Ages, relocated to the outlying city of Rungis (near Orly Airport) in 1969 and today occupies 4.2 sq km and boasts the largest turnover of any wholesale market around the world.

Fred Pouillot, the owner of Parisian cooking school Le Foodist, draws attention to this discrepancy on tours of local markets with his American clients.

Illustration of Les Halles, Paris's central fresh food market by Max Berthelin – 1811-1877

Illustration of Les Halles, Paris's central fresh food market by Max Berthelin – 1811-1877

"I ask them, only looking at the produce, 'what is the difference between what you see here and an open-air market back home?'," he said. "And then I lead them on until the 'clue' is given – bananas! We don't grow bananas around Paris! Or mangoes, or melons or anything you see here for that matter. In America, an open-air market is a normally a farmers' market. This is not a farmers' market – this is a traders' market."

While this disconnect may seem surprising, especially given France's celebrated link to its terroir, according to French culinary journalist Emmanuel Rubin, it's merely the final step in a long and complex devolution. The rapid economic development France underwent in the 1950s and '60s – a period known as the Trente Glorieuses – had, Rubin asserts, a lasting effect on the country's cities, notably with regards to the arrival of supermarkets on the outskirts of town centres that negatively impacted the availability of small shops within. This, Rubin said, "modified French and urban dining habits in a lasting way", radiating from the home into the restaurant industry.

The imposing gastronomic pedigree of Paris' robust technical arsenal made it easy for Parisian restaurants to coast on their reputations alone

Perhaps even more essential to Paris' disconnect with the local landscape is its style of cooking. The imposing gastronomic pedigree of Paris' robust technical arsenal (as opposed to the ingredient-driven mindset that governs, for instance, Italian cuisine) made it easy for Parisian restaurants to coast on their reputations alone. Additionally, restaurants serving mass-produced meals in France became so prevalent that in 2014, the government approved a label to affirm that the dishes being served were actually being made in-house.

Auberge de la Roche relies exclusively on products from within a 50km radius

Auberge de la Roche relies exclusively on products from within a 50km radius

Of late, however, as part of a growing resistance against industrialised food, many of Paris' top chefs have started reducing their reliance on Rungis – where, Lavadenz asserts, vegetables are "calibrated and covered in plastic or cardboard" – in favour of partnerships with sustainable cooperatives and networks like Terroirs d'Avenir, Agrof'ile or Tom Saveurs. But for some chefs, venturing into the countryside themselves is a logical next step – something, Lavadenz posits, "makes the job more interesting" for these culinary professionals, who now have a hand, not just in choosing, but in growing their ingredients.

Loïc Martin and Édouard Bergeon have been growing much of their own produce for their Martin wine bar and Robert restaurant – both in Paris' 11th arrondissement – for seven years, ever since Martin bought land on the banks of the Loire River, almost on a whim. The plot of countryside has since become the Jardin-sur-Loire.

"At the beginning, it was just to feed the restaurants in Paris," said Martin. But in 2021, the pair expanded their portfolio to include Les Terrasses de l'Ile, a nearby guinguette (country restaurant), complete with a tiny house perfect for hosting visitors.

Bertrand Grébaut's D'Une Ile is a B&B and restaurant located in the Perche

Bertrand Grébaut's D'Une Ile is a B&B and restaurant located in the Perche

Bertrand Grébaut houses Parisians in slightly more luxe fashion at his D'Une Ile, a B&B and table d'hôte (fixed menu restaurant) in the same Perche region that also tempted Chartier from the capital. The Michelin-starred chef of the infamously impossible-to-book Septime in Paris' 11th arrondissement said he wasn't necessarily looking to create a new venture outside Paris when, in 2017, he and his business partner, Théo Pourriat, started to think about new projects to add to their portfolio.

"It was pretty vast, at that point," he recalled of the breadth of ideas he and Pourriat were considering. "But at the end of the day, we were attracted by the idea of finding a pretext to be closer to nature. To put our feet somewhere green."

Once he'd visited the B&B, the choice was made in an instant. "It's hard to not fall in love at first sight when you get to D'Une Ile," said Grébaut.

The irresistibly charming estate is comprised of a small grouping of 17th-Century stone buildings in the heart of Le Perche Regional Nature Park. Light stone and dark wood create a peaceful, rural and rustic environment with food to match.

Cauliflower brioche at D'Une Ile

Cauliflower brioche at D'Une Ile

"We were getting emotional over radishes and butter," recalled Grébaut, "because we were growing our own radishes, because we were making butter in-house, and because when we serve the radish, it was harvested two hours ago and it's never seen the fridge."

Tapping into local terroir is at the heart of the project at Auberge de la Roche, as well.

"The idea was to create a space that was really rooted in its environment," said Chabat of her mountain oasis, whose kitchen relies exclusively on products from within a 50km radius, meaning that the menu is often left to the whims of Mother Nature.

We were getting emotional over radishes and butter

"When there's a storm, we've got no fish," she said, implying how they often need to make adjustments on the fly. However, the restaurant's team has built a network of local producers, such as Sandrine Giraud, who cultivates her own heirloom grains; and Lawry Calendra, who produces pork that Chabat describes as "totally insane". And with chefs Riel and Bijaoui in the kitchen, Auberge de la Roche is on par with any fine dining restaurant you'd find in the French capital – with a price tag to match. A room at Auberge de la Roche clocks in at €350, and the seven-course prix fixe menu costs €90.

But even at D'Une Ile, where rooms are priced at €85 a night and dinner costs €39 for a rustic three-course menu, "locals think we're really full of it, with a radish-and-butter dish at €5.50," Grébaut said.

D'Une Ile serves dishes made from home-grown, quality ingredients

D'Une Ile serves dishes made from home-grown, quality ingredients

This reflects an innate friction that often surfaces when Parisians abscond to the countryside, with their affinity for curated rusticity. Locals who arrive at D'Une Ile, according to Grébaut, baulk not just at the "Parisian" prices but at the "mismatched, flea market chairs" and simplicity of the food.

"They were kind of disappointed that this was the restaurant that the Michelin-starred Parisian chef who just showed up in the Perche decided to open," he said, noting nevertheless that the simple approach to home-grown, quality ingredients, is "our idea of luxury".

Martin noticed a similar disconnect upon opening Les Terrasses de l'Ile last year.

"We closed again quite quickly," he said, explaining that in addition to challenges linked to the re-emergence from lockdown, he found that many locals were suspicious of his arrival.

"This is a France that is feeling a bit forgotten," he said, noting that a group of Parisians taking over the restaurant that had, for 25 years, served a buffet beloved by regulars meant that "there were loads of things locals didn't like" about the new approach, which was perhaps better suited to Paris than to the French provinces.

Terrasses de l'Ile is a guinguette (country restaurant) on the banks of the Loire River

Terrasses de l'Ile is a guinguette (country restaurant) on the banks of the Loire River

"It was awful for the team," Martin said, "so it was better to shut down."

It probably doesn't help that with these new arrivals comes an uptick in housing prices. At just more than an hour from the French capital, the bucolic Perche in particular is now home to a host of ex- or part-time Parisians. Local cocktail expert Forest Collins can attest to the expensive result of having such high-profile neighbours, noting that in her hamlet, somewhere between a quarter and a third of houses have become weekend homes for city-dwellers and that local brocantes (flea markets) have considerably hiked their prices as a result.

Martin has since switched gears at Les Terrasses de l'Ile, which reopened this spring with a simplified menu that better caters to the local population. Egg mayonnaise, house-made terrine, mussels and French fries, or sausage with mashed potatoes are all made with 90% local ingredients and served at prices in-line with other offerings in the area.

"We took a step back," he said. "It was the right idea. The right choice."

Edward Delling-Williams, owner of Paris' Le Grand Bain, made a similar choice with his new venture in Normandy. Like many others, Delling-Williams had been itching to leave the city before finally taking the plunge during the pandemic, happening upon Heugueville and falling immediately in love with the north-western coastal village.

"It was springtime, and it was unbelievable," he said. "There was wild garlic everywhere."

Mussels with white asparagus and squid ink sauce at Le Presbytere

Mussels with white asparagus and squid ink sauce at Le Presbytere

He opened The Presbytère this spring in a former vicarage just steps from the beach. Bit by bit, it will be fuelled by more produce grown on his land, which the previous owner spent 12 years renovating "almost exactly how we would have done it", Delling-Williams said. "He's planted 6,000 trees. He's made safe spaces for animals. There's solar power. It's really unbelievable."

For the British chef, who also implemented a local mindset at Le Grand Bain, the move was a logical next step, a break from the monotony that had come to small plate-focused, natural wine-driven, contemporary Parisian restaurants – including his own.

Everything is going to be local, so why not cater to the local population?

"That style of food is now just everywhere," he said. "If I brought you four dishes from four different restaurants, Le Grand Bain included, you wouldn't be able to pick which restaurant made which dish. And that seems a bit boring, now."

At The Presbytère, Delling-Williams instead serves a combination of accessible French bistro fare (like house-made pâté or skate wing in butter sauce) as well as the food typical of the English pub he was raised in, including a Sunday roast. And the prices match the locale: around €18 euros for lunch, €30 for dinner.

"Everything is going to be local," he said, pointing to the sea purslane and sea aster growing wild around the restaurant. "So why not cater to the local population?"

Chef Edward Delling-Williams opened Presbytère in a former vicarage just steps from the beach

Chef Edward Delling-Williams opened Presbytère in a former vicarage just steps from the beach

"If the Parisians want to come," he added, "they can come." But he's doing nothing to overtly attract them. His focus is less on becoming an innkeeper than a brewer, a baker, and, above all, a producer of his own ingredients.

"I'm pretty sure that if you talk to any chef, they're going to come up with the same sort of reason: having control over the produce," he said of his motivations. But then he prevaricated: "Maybe I'm just becoming an old man and I want to be in the countryside. I think that's probably it."

Age aside (the father of three is just 36 years old), others may soon follow suit. Martin, notably, thinks that he, too, will eventually make his part-time move to the Loire more permanent.

"I think that, in time, we might be happier raising animals and making our products there," he mused, "rather than being in Paris five days a week."

The French capital's love of local is certainly on the rise, with restaurateurs realising that tapping into the richness of the surrounding countryside has become an expectation rather than an exception for many Parisian diners. But watching Delling-Williams traipse across his land with young sons in tow, inviting them to smell fresh spring garlic and pull radishes from the soil, it's perhaps no wonder that he's not the only chef with greener pastures on the mind.