The unprecedented surge was not triggered by the national security law imposed by Beijing on June 30 but it continued unabated in the first half of 2020.

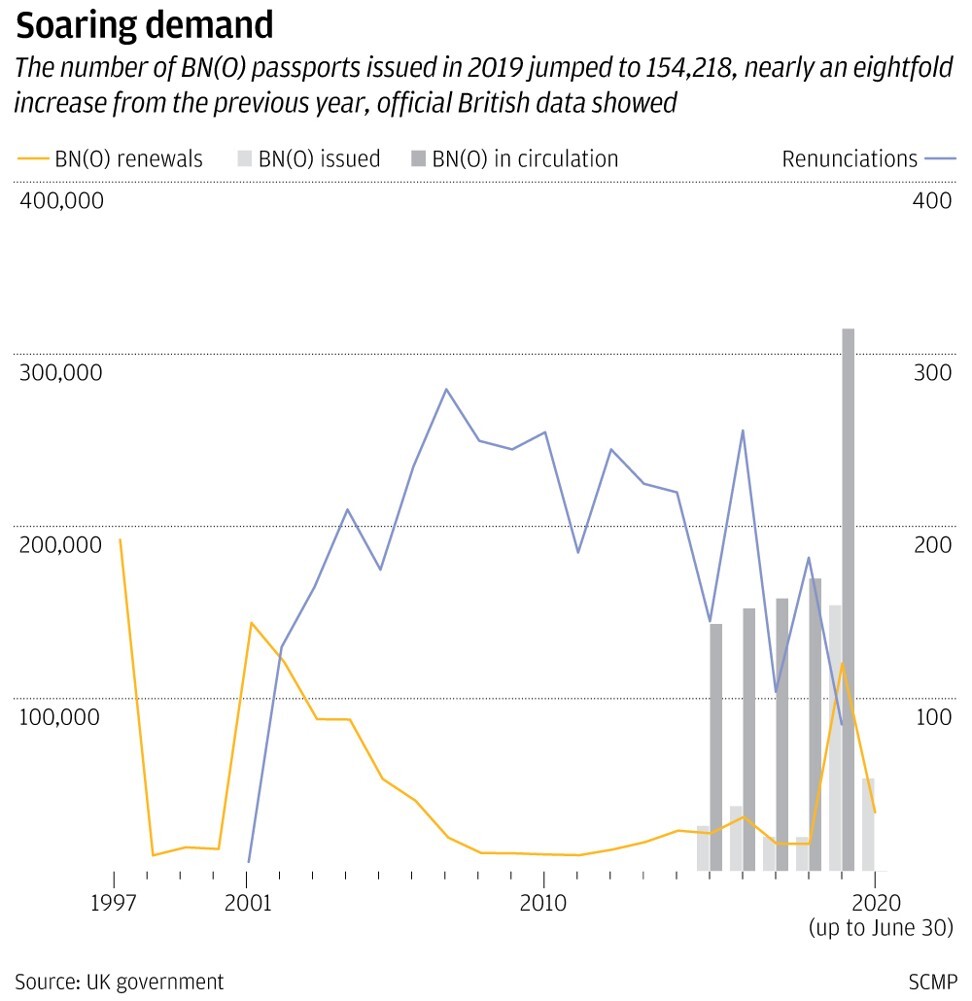

Hongkongers renewed their British National (Overseas) passports or applied for the travel document in record numbers in 2019 when the city was rocked by months of anti-government protests, marking an eightfold increase over all applications in 2018.

The unprecedented surge was not triggered by the national security law imposed by Beijing on June 30 but it continued unabated in the first half of 2020 and anecdotal evidence suggests it was further fuelled by fears sparked by the draconian legislation.

By July this year, those who succeeded with their renewals and applications found themselves in possession of a more valuable document when Britain undertook a major policy shift to allow Hongkongers a clear pathway to citizenship.

Data obtained by the Post through a British government Freedom of Information Request showed the total number of identity documents issued in 2019 soared to 154,218, nearly an eightfold increase from the previous year.

The number who applied to renew their passports in the same period went from 14,297 to 119,892.

This year, there have been some 32,813 renewals up to the end of June, becoming the second largest volume of renewals since 2006 and on pace to rise significantly as anecdotal evidence suggests the vast majority of applications have yet to be processed.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced in July that millions of Hongkongers with BN(O) passports would be able to resettle in the country and be offered a path to citizenship after the national security law came into effect.

The new policy offered millions of BNO passport-holding Hongkongers, their spouses, and children the chance to resettle, by giving them five years to remain in Britain after which they could apply for settled status – effectively giving them permanent residency.

The security legislation targets acts of secession, subversion, terrorism as well as collusion with a foreign country or external elements to endanger national security, with life imprisonment the punishment for the most serious offences.

Commenting on the data, Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, a heavyweight pro-establishment lawmaker, said the figures were not surprising but the reasons for people wanting to leave Hong Kong were many.

“There have been various crises and jitters, crises of confidence from Hong Kong in the past 40 to 50 years, this is not new,” Ip said. “People could be planning for different reasons, might be worried about erosion of freedom, but there are plenty who dislike the violence and unrest. You can’t draw a conclusion.”

The ex-security minister pointed out that the actual number of people who left Hong Kong was a different matter and that many emigres had also returned from Britain, Canada and Australia.

Ramon Yuen Hoi-man, convenor of the BN(O) rights concern group, said Hongkongers on both sides of the political divide were deeply shaken by the events of last year.

“Democracy activists and supporters might have applied for renewal as an insurance policy and a fallback option if life in the city no longer works out for them,” the Democratic Party district councillor said.

“But equally, many people in the pro-establishment camp are worried about the economic repercussions of the protests and possible sanctions by the United States, and may want to start a better life afresh elsewhere.”

BN(O) passports were issued to Hongkongers born before the 1997 handover, and under previous rules, could visit Britain for up to six months but were not able to work or apply for citizenship. Britain’s latest moves to open up a pathway angered Beijing, which accused London of breaching the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

Most recent figures indicate there are almost 350,000 holders of BN(O) passports and around 2.9 million, who used to hold the document, are eligible to apply for them. In fact, by 2018, just 170,000 Hongkongers held BN(O) passports, underscoring the rapid take-up to renew or apply.

Andrew Lo, CEO of Anlex, an immigration consultancy in Hong Kong, said inquiries on emigration applications to Britain skyrocketed 20- to 30-fold after July from a “relatively low” base. His firm now receives on average more than 10 inquiries per day. More than a dozen of his clients had made the move since July, he estimated.

“Few people chose to emigrate to Britain because of its high living cost, but many people expressed interest after the UK government made a generous offer to BN(O) holders in July. Some of my clients even switched their plan from an investment emigration to Canada or Taiwan, to moving to Britain.”

Prior to Britain making the historic change or the security law taking effect, a British government briefing document cited “internal projections suggest many will want to stay in Hong Kong, or relocate temporarily to the region”.

However, its projections were said to be heavily influenced by “what action the Chinese government takes in relation to Hong Kong and the ball in their court”.

Lo said last year’s protests and the controversial national security legislation were the driving force behind the exodus, and he observed a material change in the nature of the inquiries.

The surge in renewals comes amid a huge backlog of people renewing BN(O) and ordinary British passports this year – both worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic and fewer officials to process applications.

The British government’s own figures as of July 7 said it was actively processing 126,000 passport applications, 31 per cent higher than the same period last year. A further 284,0000 were in the queue – a jump of 172 per cent.

In late May, around the same time Beijing decided to press ahead with the national security law at its annual parliamentary session, Britain saw inquiries from concerned Hongkongers jump eightfold.

Angela Ko, an advertisement industry worker, renewed her BN(O) passport last year for travel reasons, but the protests and the national security law made her think seriously about settling in Britain permanently.

“I would be doing it for my mental health more than anything, because the past year has just been so depressing for anyone just reading the news,” the 31-year-old said. “It would also not be the place I want to bring up my children if I were to start my own family later.”

Ko said she would start by applying for a master’s programme in a British university for the coming academic year, and find a job in a related field there after graduation, creating a path that would eventually lead to citizenship in the country.

Lea Chu, a publishing business owner in the city, submitted an application to renew her BN(O) passport in June as an “insurance policy”, but now she feared she might actually have to use it.

“My parents queued for hours in 1996 before the handover to get me the passport, but like many people in Hong Kong, I didn’t renew it until this year when things really got so much worse,” the 27-year-old said.

Chu said she did not feel the law would affect her personally, but it might change her city of birth beyond recognition. “I would not want to live here any more if it’s not the free, human rights-respecting Hong Kong that I know.”

Even though she admitted practical difficulties in relocating her business of Chinese publishing to Britain, she said she had started saving up and had spent more time researching about the practical steps required for emigration than ever before.

John Leung, another millennial prepared to give up his residence in his home city, said he became fed up with life in Hong Kong after the government showed no leadership in resolving any difficult issues it faced.

“It’s not just the political problems. You just feel you are getting nowhere in the city with your job, housing and other opportunities. So why shouldn’t I move?” said the 30-year-old office worker who submitted his BN(O) renewal application in May.

Renunciations remained steady with 185 people last year cancelling BN(O) passports, despite the increased rhetoric by pro-Beijing supporters over possessing the document.