Scale of mental health crisis in prisons has escalated during Covid pandemic, Guardian investigation finds

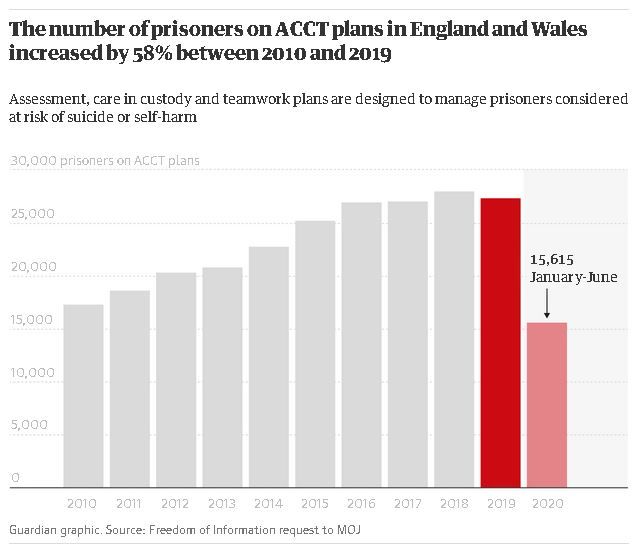

The number of prisoners put on suicide or self-harm watch has risen dramatically over the past decade, a Guardian investigation has found, as experts warn the scale of the mental health crisis in prisons has escalated during the coronavirus pandemic.

There were 15,615 prisoners put on ACCT (assessment, care in custody and teamwork) plans – which are designed to manage those at risk of suicide or self-harm – during the first half of 2020, only 10% less than the figure for the whole of 2010.

Data obtained from the Ministry of Justice reveals that during 2019, the last full year for which figures were available, 27,389 people in prisons in England and Wales were put on ACCT plans.

That is an increase of almost 60% on the 17,314 put on a plan in 2010. The steep rise in numbers comes despite the average yearly prison population having fallen slightly over that period, from 84,725 in 2010 to 82,935 in 2019.

Prisoners and prison staff have raised the alarm that the mental health crisis in prisons has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has led to prisoners being confined to their cells for most of the day, and restrictions on visits and prisoner education programmes.

Mick Pimblett, the assistant general secretary of the Prison Officers’ Association, said the prison system was overwhelmed with prisoners with mental health problems. “Although Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) have attempted to address the problem by appointing mental health practitioners within prisons, in effect they are just putting a plaster on a broken leg,” he said.

“Prison officers are given mental health awareness training but this is insufficient for the job that they undertake. Because of this our members are continually faced with violence, self-harm and suicide from frustrated prisoners, which is having an adverse effect on staff mental health.”

Figures published by the Ministry of Justice last month showed there were 58,870 self-harm incidents in prisons in the 12 months to September 2020, down 5% from the previous 12 months. That figure comprised a 7% decrease in male prisons and a 8% increase in female prisons.

In the most recent quarter, however, there were 14,167 self-harm incidents, up 9% on the previous quarter. That represented a 5% increase of these incidents in male prisons and a 24% increase in female prisons. There were 67 suicides in the 12 months to December 2020 and 85 in the previous 12 months.

Deborah Coles, the director of Inquest, a charity that provides advice and support to families of those who die in custody, said it was important to remember that the high figures for people on suicide and self-harm watch represented “real people in extreme distress”. She said: “Prisons generate and exacerbate mental ill-health. At a time of such restrictive and dehumanising regimes this is even more acute.”

When the pandemic hit the UK in March, prisons were placed under a severely restrictive regime, which reduced the time spent out of cells to about 30 minutes a day and limited visits from friends and family. In October, the outgoing chief inspector of prisons in England and Wales said locking up prisoners in what amounted to solitary confinement under Covid restrictions risked causing irreparable damage to their mental health.

Peter Clarke said the government should see the crisis as a chance to “reset the aspirations for what prisons could be about” and that, despite the pandemic, underlying systemic problems of drug use, violence and self-harm, had not gone away.

Nick Hardwick, the former chief inspector of prisons and professor at Royal Holloway, University of London said the mental health crisis in prisons had two root causes: the deterioration in conditions inside prisons, which he said started with drastic cuts to staffing in the early years of the coalition government and the departure of many experienced professionals; and the fact that those with pre-existing mental health conditions were being given custodial sentences instead of treatment, which itself can be linked to a lack of resources in mental health care.

“There is a whole chain of events, which leads to people whose basic issue is a health one, being treated by the criminal justice system,” he said.

“You’ve got to look at the issue [of mental ill-health in prisons] from both sides. Why are these people ending up in prison in the first place? Why aren’t they getting the care and support they need in the community? And when they do end up in prison – where you’ve got this difficult volatile mix of prisoners – there are reduced resources available to look after them.”

ACCT plans are opened for prisoners who are identified as being at risk of suicide and self-harm, and can be in place for a number of days, or – in some cases – months and years. The plans require staff to take certain measures to ensure someone is safe, including regular observations.

Peter Dawson, a former prison governor and the director of the Prison Reform Trust said the fact that the number of ACCT plans being opened was rising demonstrated what “prisons are being asked to cope with”.

“It’s not right to criticise prisons for opening that many plans. But it raises a very serious question about whether we understand who we are sending to prison and the distress that decision creates and the consequences that flow from it.”

Pimblett said the POA was concerned about whether, with the dramatic increase in the use of ACCT plans, “these processes can be sufficiently followed (particularly at night) when there is simply not enough staff to ensure that effective observations take place”.

Responding to the figures on the numbers of people on ACCT plans, a Prison Service spokesperson said: “On average, less than 5% of prisoners were on an ACCT plan at any one time over the past 12 months.” They said the number of prisoners placed on suicide and self-harm watch in the whole of 2020 would not necessarily be double the figure for the first six months of that year.

They said self-harm remained far too high. “That is why we have trained more than 25,000 staff to help prevent it, provided one-to-one support for vulnerable prisoners, and bolstered security to keep out the drugs that can fuel mental health issues.”