Even those who make the effort to blend in by learning Cantonese say their mainland accent is enough for Hongkongers to shun them

Demi Cao walks an extra 10 minutes to buy groceries each day because she became tired of the market vendors in her neighbourhood telling her to go back to mainland China.

Over five years living in the city, she has been rejected for jobs because she is a mainland immigrant, and even when she landed work as a waitress or supermarket cashier, her Hongkonger colleagues and superiors excluded her and made her do more work.

Cao, 29, says they insulted and laughed at her, and called her names for wearing high heels instead of trainers or speaking Cantonese, her mother tongue, with a mainland accent. Once, a supermarket colleague deliberately locked her in the freezer for an hour.

“I was called ‘Princess Mainland’. I felt upset at first, and then I grew numb,” Cao says.

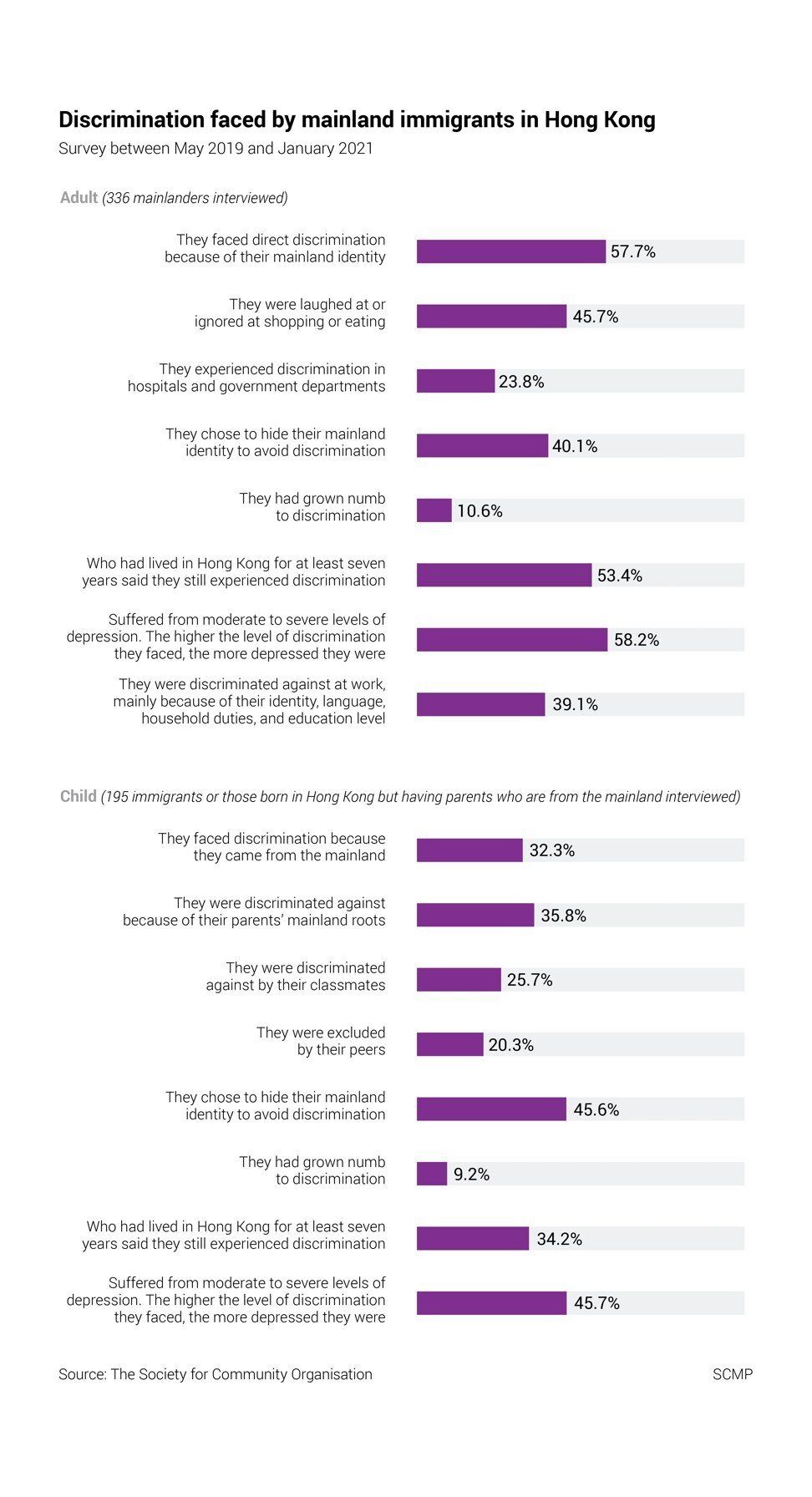

A new study released last month by the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO) found that among those surveyed, nearly three in five adult mainlanders and about one in three child immigrants from the mainland or those born in Hong Kong to mainland parents faced discrimination.

Hong Kong’s bustling Sham Shui Po neighbourhood is home to numerous low-income families from the mainland.

Hong Kong’s bustling Sham Shui Po neighbourhood is home to numerous low-income families from the mainland.

Like Cao, many complain about being insulted, ignored and treated unfairly by local Hongkongers in daily life and at work, saying this persists no matter how long they have been in the city.

Social workers and experts say this experience has hindered many from assimilating into Hong Kong society, contributed to continuing intergenerational poverty and taken a toll on their mental health as well.

“I never expected to be treated like that,” says Cao, who came to Hong Kong from Guangdong province in 2016 to reunite with her husband, a Hongkonger she married in 2011.

She became depressed soon after arriving, could not sleep at night or had nightmares. She attempted suicide by swallowing half a bottle of sleeping pills, but her husband found her and took her to hospital.

The couple divorced and she later remarried another Hongkonger, a 38-year-old construction worker. They have a 2½-year-old son, and live in a 100 sq ft cubicle unit in Cheung Sha Wan.

It took time, but she says she eventually learned to cope. “I have adapted to the local lifestyle, and others don't realise I’m from the mainland now,” she says.

Mainlanders who come to Hong Kong to work, study or reunite with their families must live in the city for at least seven years to obtain permanent residence.

Under a one-way permit scheme, up to 150 mainland residents are allowed to arrive daily for the purpose of family reunions. More than a million have come since the city returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

In 2018, 42,331 made the move, but the number slid to 39,060 during the social unrest of 2019. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, the scheme was suspended from February to June last year, with just 10,134 arriving in all.

In the first half of this year, 7,363 one-way permit holders have entered Hong Kong, according to official data.

‘I don’t want to create a scene’

Between May 2019 and January 2021, SoCO surveyed 336 adult mainlanders and 195 children who were either from the mainland or born to parents who were mainlanders, to ask about their treatment in Hong Kong and its impact.

The adults who said they faced discrimination described being laughed at or ignored by service staff while out shopping or eating, and nearly one in four complained about their treatment at hospitals and government departments.

The children who said they experienced discrimination said it was because they or their parents were from the mainland, and that they were shunned or humiliated by classmates and peers.

After 16 years of living in Hong Kong, Wei, 59, still feels nervous when he speaks in public, because he knows his accented Cantonese is a giveaway.

“They can tell that I’m from the mainland the moment I start talking,” he says. “It makes no difference that I’m already a permanent resident and have lived here for so long.”

Originally from Jiangxi province in southeast China, the masseur came to Hong Kong in 2005, a year after he married a Hongkonger, and became a permanent resident in 2012.

Asking to be identified by only his surname, he recalls being taken aback by the dilapidated housing and the poor treatment from locals when he arrived.

Neighbours shunned him and colleagues excluded him. Although he made an effort to pick up Cantonese, some insulted him and told him to go back to the mainland. On hearing his accent, some vendors refused to serve him.

Now divorced and earning about HK$10,000 a month, he lives with his daughter, 12, and son, 10, in a 200 sq ft subdivided unit in Sham Shui Po, paying HK$5,500 a month.

Due to Covid-19 restrictions, just 10,134 mainlanders made the move to Hong Kong in 2020.

Due to Covid-19 restrictions, just 10,134 mainlanders made the move to Hong Kong in 2020.

Wei says he did not dare to go out during the social unrest in the latter half of 2019, as there was a strong anti-mainland sentiment.

Then came the pandemic, first reported in China’s Hubei province, which led a group of Hong Kong restaurants and other businesses to bar mainland customers and those speaking Mandarin.

Wei said some of his clients cancelled their appointments because they feared being infected by him, even though he had not crossed the border.

He says he never confronts those who look down on him.

“I don’t want to create a scene or make a bad name for mainlanders,” he says. “But Hongkongers have a wrong impression of us. We are not the monsters they think we are, here to take their resources.”

He adds that he relies on himself and has never sought government support.

‘Discrimination serious, deep-rooted’

SoCO deputy director Sze Lai-shan says there are deep-rooted stereotypes about mainlanders, and Hongkongers lack an understanding of them, their culture and lifestyles.

“Many Hongkongers regard mainlanders as backward, poor and greedy for the city’s welfare resources, and call them ‘locusts’,” she says. “But that is not true.”

Regular surveys by the non-governmental and human rights advocacy group have found that ill will towards mainlanders has long existed in Hong Kong.

But Sze says that unlike in the past, when most of the bigotry was private and personal, mainlanders are now being targeted openly by individuals and groups, and especially on social media.

Sze says although the latest survey coincided with the social unrest and the pandemic, when most people stayed at home and reduced contact with others, it still found that a high proportion of mainlanders experienced discrimination, including children.

It was the first time the survey included children, and she was surprised to see the high proportion with unhappy responses.

“Discrimination against mainlanders is serious and deep-rooted in Hong Kong,” she says.

Sze Lai-shan, deputy director at the Society for Community Organisation,

told the Post she was surprised by how many children surveyed said they

were unhappy.

Sze Lai-shan, deputy director at the Society for Community Organisation,

told the Post she was surprised by how many children surveyed said they

were unhappy.

Housewife Cai, 39, who came from Guangdong in 2017, is worried about her children being targeted.

Her husband, 42, is a Hongkonger and they live in a 100 sq ft subdivided unit in Sham Shui Po with their daughter, eight, and son, seven.

Recalling an incident soon after Covid-19 hit the city early last year, she says her husband and daughter were in a shop buying hygiene products when someone in the line overheard him replying in Mandarin to a voice message on his phone.

The other shopper began insulting her husband and daughter, refusing to stop even when he showed his identity card.

“When my daughter told me what happened, I was shocked. How has Hong Kong come to this?” says Cai, who asked to be identified by her surname.

Nearly three in five adults and almost half the children in the SoCO survey said their unhappy experiences left them feeling sad and depressed, affecting their sense of security and belonging in Hong Kong.

Mainland immigrants are changing

Dr Zhang Hongliang, an associate professor with the department of economics at Baptist University, says that from an economic perspective, discrimination against mainland immigrants is a result of Hongkongers’ perception that most are one-way permit holders who are generally poor and a burden on the city’s welfare system.

“But the picture has been changing,” he says.

Zhang is one of the researchers behind a study released in June that revealed a substantial rise in the socio-economic status of mainland immigrants between 2001 and 2016.

The proportion with tertiary education or higher increased from 5.7 per cent in 2001 to 19.5 per cent in 2016, while 8.5 per cent held a master’s degree, compared with 4.9 per cent of Hong Kong’s population.

The median monthly household income of mainland immigrants also rose by 45 per cent, from HK$12,050 in 2001 to HK$17,490 in 2016.

The researchers found that the proportion of one-way permit holders among mainlanders in the city declined from more than 80 per cent in 2001 to about half in 2016.

The proportion of mainland immigrants in public rental housing units in 2016, meanwhile, was similar to that of the city’s whole population, about one in three.

Zhang says the study revealed that mainland immigrants helped counteract the effects of the ageing population and boost the city’s economy.

He adds that the government can do more to protect mainlanders, including intervening in cases of discrimination and exploring legislative measures.

Hong Kong’s four existing anti-discrimination ordinances concern sex, disability, family status and race, but do not address mistreatment on the grounds of being from the mainland.

SoCO’s Sze suggests amending the Race Discrimination Ordinance to make it unlawful to discriminate against a person on the grounds of residential status and place of origin.

There are several NGOs and community groups helping mainlanders in Hong Kong, including support groups for people from the same mainland province or city.

SoCO serves about 5,000 households with mainland members, and organises events and activities for new arrivals and their children to learn about the Hong Kong culture and build connections.

Sze says it helps mainlanders adapt better if they learn Cantonese, but they should speak out against mistreatment.

Li Mei-oi, 68, came from Guangdong in 1997 to reunite with her Hongkonger husband, now 76. Despite feeling a little stressed at first about her mainland roots, she says she has not experienced much discrimination.

She recalls that as a new immigrant, she observed how the locals spoke and did things, and learned to adapt.

Sometimes, when she heard someone insulting mainlanders, she would try to defend them. But on other occasions, she just walked away and did not take it to heart.

For a few years, when she stayed home taking care of her three daughters, the family relied on the government‘s Comprehensive Social Security Assistance monthly allowance. Other than that, she has worked, taking jobs as a domestic helper and cleaner until she retired a few years ago.

Now a grandmother of three and living with her husband and their oldest daughter, Li says: “I feel confident to tell others I’m from the mainland, and that I have lived in Hong Kong for so many years and contributed to this city.”

Another mainlander who says he has not faced much discrimination is Jack Xu, 31, who came to Hong Kong in 2014 to pursue a master’s degree and now works in insurance.

Originally from Zhejiang province, he recalls being nervous initially about speaking Mandarin in public. But he made an effort to learn Cantonese and now speaks it with his Hongkonger colleagues and friends.

Xu says he has chosen to live in the city for the job opportunities and because he feels he blends in. He became a permanent resident this year.

“As long as you are confident, open-minded and make efforts to adapt to local society, Hong Kong is still a beautiful city,” he says.