Children are Hong Kong residents, but single parents from mainland don’t qualify for one-way permits to let them stay, find jobs.

On many nights, Zhang Xionglian cries silently under her quilt so her teenage daughter sleeping beside her will not notice.

The 49-year-old from mainland China has been on her own in Hong Kong and taking care of her child, 13, since her Hongkonger husband had an asthma attack and died in 2008, just days after the girl was born.

She has been stuck in limbo ever since. While her daughter is a Hong Kong resident, Zhang has been unable to get a permit to settle in the city permanently or get a job.

Instead, she stays on a visitor visa, which she must renew by going to the mainland every three months.

With border controls in place during the coronavirus pandemic, the Hong Kong Immigration Department allowed her to extend her stay.

A woman and child arrive via the border crossing at the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge.

A woman and child arrive via the border crossing at the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge.

Mother and daughter survive on the girl’s Comprehensive Social Security Assistance welfare allowance of about HK$5,000 (US$643) a month. Half of that goes towards their rent for a 100 sq ft room in a two-bedroom flat in Sham Shui Po.

“I want to settle here and work so I can live on my own and provide my daughter a better life. But I can’t do anything now,” says Zhang, who came to Hong Kong from Guangxi province in 2005 when she married her late husband.

The plight of single parents such as Zhang has led to calls for authorities to find ways to allow these mainlanders to remain permanently and build new lives with their families.

In 2019 there were 19,557 cross-border marriages – 12,563 between Hong Kong men and mainland women, and 6,994 between Hong Kong women and mainland men.

The number of marriages plunged to 3,266 last year, as strict border control and quarantine measures kicked in with the pandemic.

The children of such unions are Hong Kong residents upon birth, but mainland spouses must wait an average of four years for a one-way permit to be with their families in Hong Kong. After staying in the city for at least seven years, they can obtain permanent residence.

But mainlanders who are divorced or widowed before receiving their one-way permit end up stuck, like Zhang, if they have children who are Hongkongers. They cannot apply for the permit through their children.

Social workers estimate there are 3,000 to 5,000 families caught in this situation.

To be with their children, the mainland parents have to keep renewing their visas. They do not have a Hong Kong identity card, cannot work and are excluded from public services, including medical care and welfare.

A survey by the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO) found that these single parents, mostly women, and their children face financial pressure and mental stress, and Covid-19 has made their lives even harder.

The parents were excluded from the government’s anti-pandemic relief measures including cash handouts and free masks, and the vaccinations were only made available to them from May.

Cross-border travel restrictions ended their mainland visits, including for those who went to the mainland to work.

Zhang used to earn some extra cash by taking skincare products from Hong Kong to her friends across the border, but that had to stop.

“It has been so hard all these years. I feel helpless and hopeless,” she says.

Sze Lai-shan, deputy director at the Society for Community Organisation.

Sze Lai-shan, deputy director at the Society for Community Organisation.

Depressed and stuck in limbo

SoCO interviewed 57 single mothers from the mainland with Hongkonger children in April. Most were divorced, and 10 were widowed.

All were in the city on visitor visas and had taken care of their children for an average of nine years. About half had been living like this for 10 years or longer.

More than half the families survived on the children’s monthly welfare allowances, while others borrowed from relatives, held jobs on the mainland, or ate into their savings.

Their median monthly household income of HK$5,720 was only about one fifth that of all households in Hong Kong.

“The problems they face have long existed, but the pandemic has made their lives even more challenging,” says Sze Lai-shan, SoCO’s deputy director who led the survey.

Nearly nine in 10 of the mothers and more than a third of the children did not have three proper meals a day during the pandemic, the survey showed.

Most of the mothers do not go to hospital when they fall sick. They can only go to private hospitals, or the accident and emergency services at public hospitals, where they pay HK$1,230 per attendance compared to HK$180 for Hong Kong residents.

Many children cannot afford tuition, school uniforms, or extracurricular activities. Many do not have computers and internet access, so staying home during the pandemic and attending online classes proved hard.

Almost all the mothers and children interviewed by SoCO revealed they suffered light to severe levels of depression.

Sze says the organisation has helped about 300 such families since 2010, and most live in poverty.

Some parents who have to work on the mainland have had no choice but to leave their children in the city’s childcare homes.

“Both the parents and children are depressed, isolated and have low self-esteem,” she says.

Mainland Chinese single father Huang Shaoping, at his home in Kwun Tong.

Mainland Chinese single father Huang Shaoping, at his home in Kwun Tong.

Liu Ziwen, 43, came to Hong Kong from Dongguan, in Guangdong province, in 2007, after marrying a Hongkonger 14 years older.

She gave birth to a son and daughter, but her husband began hitting her and she called the police three times. The couple divorced in 2010, before Liu received her one-way permit.

She has remained in Hong Kong on a visa to care for her son, now 13, and daughter, 12. Their father does not help at all.

They survive on the children’s monthly welfare allowances of about HK$9,000 in total. They paid HK$5,500 a month to rent a tiny subdivided unit in Yuen Long for 10 years, before SoCO helped them rent a flat earlier this year at a subsidised rate of about HK$4,500 a month.

To make ends meet, Liu says they sometimes skip a meal and eat less, and do not buy new clothes, furniture or toys.

Amid the pandemic, each of them uses a single mask for a week, and the children took turns to use Liu’s mobile phone for online classes at home.

All the difficulties have taken a toll on Liu, who says: “I feel useless and ashamed like this. I’m capable of working to contribute to Hong Kong. All I want is for my children to grow up happily.”

Need to fix ‘grey area’ of permit scheme

Despite the hardships, most of the parents insist on staying in Hong Kong for their children who have grown up attending school in the city.

Their children do not have the mainland’s hukou – a household registration document that provides mainland citizens access to public services. Without it, they are not eligible to attend public schools, for example.

Huang Shaoping, 43, has been living in Hong Kong on a three-month visa to take care of his two sons since 2019, when his Hongkonger wife died of an influenza-related illness aged 41.

Huang, who used to do part-time work, including as a driver on the mainland, says he applied for a one-way permit in 2016, but his application was cancelled when his wife died.

He and his two sons, aged 15 and three, live in a subdivided unit in Kwun Tong, paying a monthly rent of HK$5,500. They live off the boys’ welfare allowances of about HK$10,000 a month in total.

Depression from losing his wife, whom he married in 2003, and the difficulties of being a single father have gnawed at Huang, who says he has thought of taking his sons back to the mainland but dismissed the idea.

“They were born and have grown up here. I’ll have to come to terms with all the struggles for them,” says Huang, originally from Huizhou in Guangdong.

Professor Paul Yip says the children of single parents from the mainland deserve support to be with their parents.

Professor Paul Yip says the children of single parents from the mainland deserve support to be with their parents.

Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai, associate dean of the faculty of social sciences at the University of Hong Kong, says the children of single parents from the mainland deserve support to be with their parents.

“These children are Hong Kong residents. They should not be deprived of their parents’ love,” he says.

All the single parents surveyed by SoCO said their problems would ease if they obtained the one-way permit allowing them to settle in Hong Kong, work and have access to public services.

Under the one-way permit scheme, up to 150 mainland residents are allowed to arrive daily to reunite with family members and more than a million have come since Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

It is the mainland authorities that decide who obtains the permits. Some single parents have received the permit on a discretionary basis.

Those already in Hong Kong and getting by on visitor visas deserve attention, Sze says.

She hopes the mainland authorities can allow these single parents to settle with their children in Hong Kong, and says the local government can help in this process too.

As not all the one-way permits are taken up, she suggests allocating part of the daily quota to these parents.

Statistics show an average of only 40 one-way permit holders entered Hong Kong between April and June this year.

Sze says those who have applied for the permit should also be allowed access to public services in Hong Kong.

Chung Kim-wah, deputy chief executive officer of the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, says it might help if the Hong Kong government took over from the mainland authorities and decided who should get the permits.

The government can then explore setting aside some of the 150 permits per day for those in urgent need, he says.

“Based on humanitarian grounds and considering the growth of the children, these parents should be allowed to reunite with their children as soon as possible,” he says.

Under the existing scheme, mainland single parents with children resident in Hong Kong may apply for a one-way permit to move to the city only when they reach 60 and have no one else to rely on in mainland China, and their children are adults.

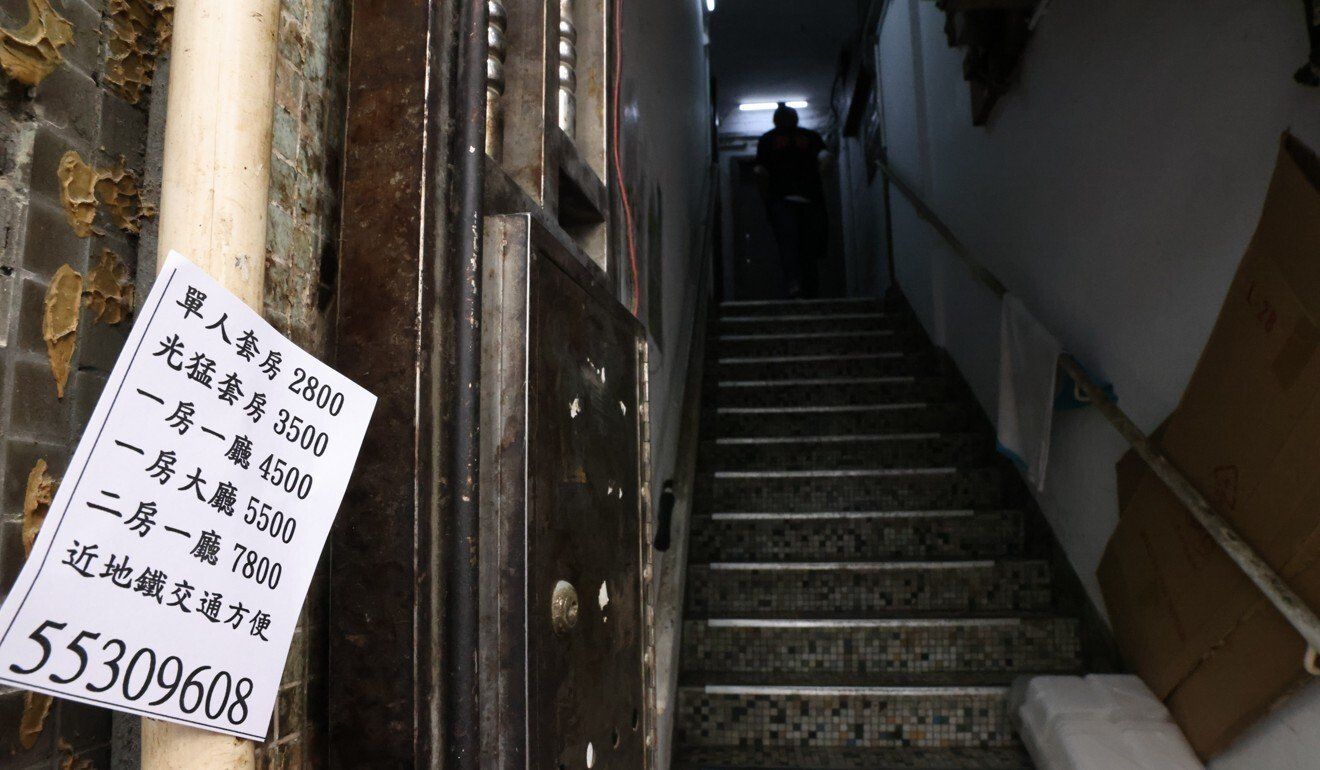

A building with subdivided units in Sham Shui Po.

A building with subdivided units in Sham Shui Po.

Lawmaker Eunice Yung Hoi-yan, of the New People’s Party, says the mainland authorities should be flexible under the one-way permit scheme to allow single parents stuck in the “grey area” of the system to reunite with their children in Hong Kong.

She also wants the Hong Kong government to provide support in education and caregiving for these children, and explore allowing the parents to work in some sectors which are short of manpower, such as domestic and elderly care, so they can get off welfare.

“The Hong Kong government has the responsibility for the well-being of these children, who are Hong Kong residents,” she says.

Lawmaker Edward Lau Kwok-fan, with the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, says the issue of single parents from the mainland who are stuck is a problem of the system.

He says the authorities should do a review and adjust the allocation of the one-way permits, with room for single parents to apply for the permit through their resident children.

“It is for the purpose of family reunion too,” he says.