POLITICO spoke with experts across the field to find out what changes now would have immediate impact on services.

The U.K.’s National Health Service is in crisis.

In the two weeks leading up to Christmas, 1,500 more people died in England and Wales than during the same period in the two previous years of the pandemic. The number of people hospitalized with flu jumped by almost a half last week, up to 5,105 patients. And this is on top of a surge in hospitalized COVID patients — which rose by almost 1,200 last week to some 9,390 patients every day — and pressure from seasonal infections like Strep A and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The soaring infections come on top of long-term problems, such as immense waiting lists for treatment and a chronically understaffed and burnt-out workforce. The result is a health service bulging at the seams. In November alone, 37,800 patients waited over 12 hours to be seen in emergency departments, compared to 10,600 in November 2021 and 1,111 in November 2019.

One doctor admitted she took a patient to hospital herself because an ambulance did not come, while ambulance staff are haunted by trying not to kill people instead of saving lives — as 25,000 exhausted paramedics went on strike over pay and conditions on Wednesday.

On Monday, Health Secretary Steve Barclay set out a series of plans. In the short-term, the NHS will bulk buy empty beds in care homes to allow 2,500 medically fit patients to be discharged from hospital over the next four weeks; expand capacity in emergency rooms with “modular units” and pause hospital inspections.

But experts believe far more is needed — and urgently. POLITICO contacted specialists in emergency care, hospital and primary care, nurses and leaders of NHS facilities to give their views on what changes, if brought in today, would improve care overnight.

Pay staff more

There will be no improvement until the current deadlock between medical staff and the government over pay and conditions — and the resulting strike action — is broken.

Miriam Deakin, director of policy at NHS Providers, which represents hospitals, ambulance, community and mental health services, called on the government and unions involved to "get round the table immediately to talk specifically about pay." Last month’s strikes meant thousands of appointments had to be rescheduled, she said.

“The strikes are piling pressure on an overstretched health service during what is already the hardest time of year for the NHS," she said. "We need to avoid escalating, prolonged strike action."

Things could get even worse if junior doctors join the industrial action. Their six-week strike ballot opened this week.

The NHS is also chronically understaffed. At the end of September last year, there were 133,446 staff vacancies across the NHS in England. That’s a 29 percent increase compared with September 2021 and a 52 percent jump from two years ago, according to NHS Digital figures.

Four in 10 junior doctors say they will leave the NHS as soon as they’ve found another job

Four in 10 junior doctors say they will leave the NHS as soon as they’ve found another job

The chronic lack of workforce “is one of the root causes of today’s situation,” said Pat Cullen, Royal College of Nursing general secretary and chief executive, in a letter to Barclay last week — not flu or COVID rates.

And it's set to worsen. Four in 10 junior doctors say they will leave the NHS as soon as they’ve found another job, reported the British Medical Association, while 44 percent of consultants plan to leave within a year.

But this can be reversed — by properly valuing staff, argued Philip Banfield, BMA council chair. Ministers need to “once and for all” show that they value clinicians, he said. Reversing more than a decade of real-term pay cuts, scrapping “absurd” pension rules that prevent doctors from continuing in work, and addressing bureaucracy and workload pressures, will help to prevent this exodus and improve retention, Banfield said.

Suspend GP targets

Primary care is struggling. Declining family doctor numbers coupled with an increased demand for patient consultations and mountains of paperwork leave stretched GPs without enough time and working long hours to keep up.

That's impacting patients. While the majority of November's 31.3 million appointments saw patients seen within a day or two, increasing numbers of people wait eight to 14 days to see their family doctor. This forces more patients to opt for emergency care, piling even more pressure on hospitals.

Cutting the paperwork around routine check-ups for people with long-term health conditions would be an immediate solution to free up precious time. While the checkups are important, they also help to determine the amount of funding a practice gets — so doctors spend a lot of time recording and coding them.

“Some targets could be suspended without harm, with the time and money allowing GPs to deliver more focused care,” said Banfield at the BMA.

The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) also wants to see a “radical review” of these box-ticking exercises (which pop up as constant reminders on GPs' screens every day), to ensure they are “proportionate and extensively reduced,” said Kamila Hawthorne, chair of the RCGP.

And many other time-consuming administrative tasks “really don’t need to be done by GPs,” said Hawthorne. These include forms for insurance companies, letters about medication for flights, driving forms, and sick notes for short-term illnesses for schools.

Bypass emergency rooms

Hospital emergency rooms are feeling the brunt of the workforce crisis, stretched primary care services and soaring infection rates.

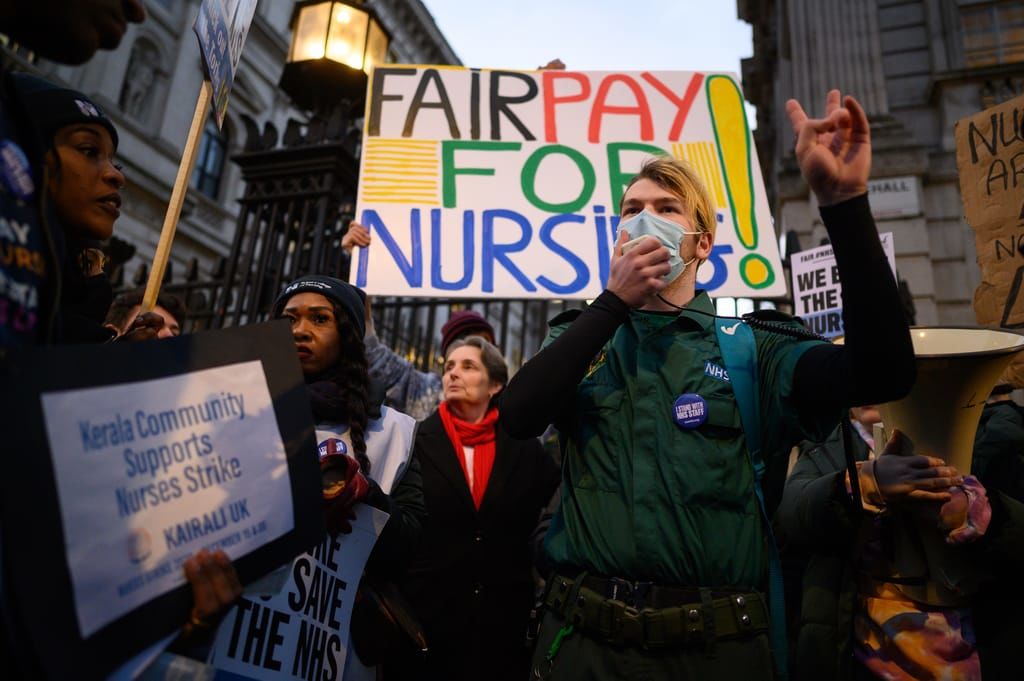

NHS workers gather outside Downing Street during a strike on December 20, 2022 in London

NHS workers gather outside Downing Street during a strike on December 20, 2022 in London

Improving communication between hospital and community teams could relieve this pressure, and lands top of a priority list of urgent recommendations from the royal colleges that represent these fields, in a December paper.

Simply having a direct line for hospital doctors to a referring family doctor could bypass being on hold at reception and save precious time. Referral and discharge information also needs to be clearer and structured, avoiding the need for further checks. The paper also calls for urgent specialist contact arrangements for people with long-term conditions who may deteriorate or develop complications of treatment.

In addition, admitting patients that need hospital care direct from the community and primary care would free up clogged emergency departments. As would establishing same-day emergency care units, known as “hot clinics.”

It's critical to "prioritize interventions that might be deliverable" because patients and clinicians fear "worsening pressures over the coming months," the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM), Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), Royal College of Physicians (RCP), Royal College of Psychiatrists, and Society for Acute Medicine (SAM) warn.

The government launched an Elective Recovery Task Force on December 7 which is due to publish urgent and emergency care recovery plans in the coming weeks. The plans will be reviewed on Saturday in Downing Street, Barclay told the House of Commons on Monday.

Work together on discharges

One of the biggest bottlenecks in moving patients onto the right ward is so-called bed-blocking — medically fit older patients unable to be discharged due to a lack of community care.

Jake Rollin, director of commissioned services and commercial support at HC-One, one of the U.K.’s largest care home providers, said a quick fix would be for winter discharge pathways to be planned by all involved — primary, acute and community carers, social workers, commissioners and adult social carers — and not done solely by hospital staff.

When implemented, this results in “well-supported additional capacity that has helped the flow of clinically fit patents out of cramped hospital wards and into bedrooms in care homes,” Rollin said.

But largely due to delayed funding, it hasn’t really happened this winter.

However, it’s not too late. “[It] can be done relatively quickly if there is a will to do so, and when the funding is in place to allow for it to happen,” Rollin said, adding that they are "standing by to engage on this basis.”

Additionally, social care urgently needs more government cash. A lack of staff — there are 165,000 vacancies — endemic recruitment and retention problems, a lack of training and career progression, and underfunding have seen the sector struggle for decades.

It’s been a political hot potato that no government has fixed, but to quickly help free up NHS beds, then this government must invest more, argued Deakin, at NHS Providers.

“Sustainable investment in social care is the obvious short-term fix,” she said. “However, this must also be accompanied by meaningful reform for the sector to ensure we have a fully functioning social care system that can provide person-centered, preventative care that allows people to stay independent in the community.”