Through lockdowns and border closures, many Asia-Pacific territories have kept deaths below a typical flu season, but now face scientific and philosophical considerations over the value of a human life.

As the Asia-Pacific’s “zero-Covid-19” economies pick up the pace of their sluggish vaccination drives, a difficult question looms on the post-pandemic horizon: how many deaths should a society accept?

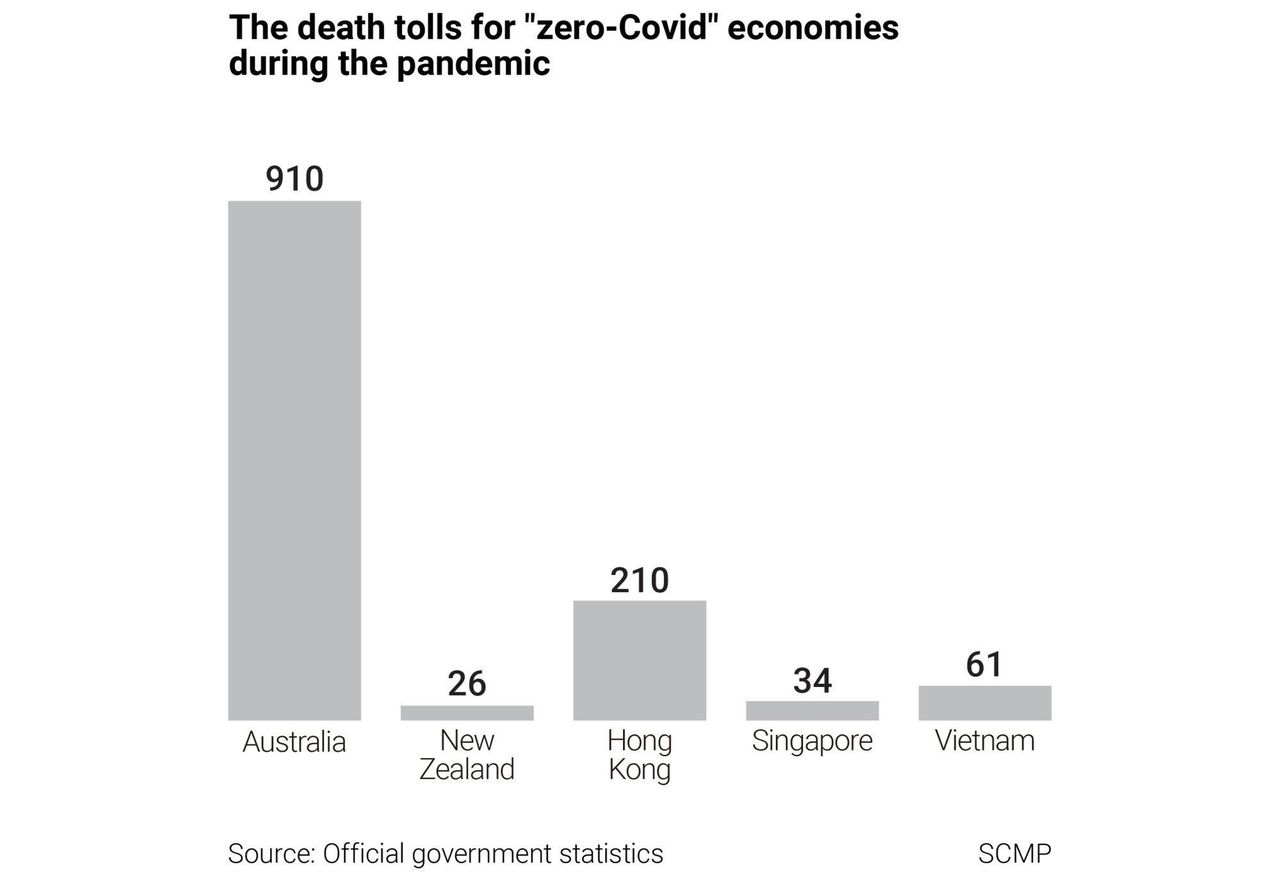

Even if they can achieve high vaccination rates, low-Covid-19 bubbles such as Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Singapore and Vietnam– which saved countless lives with border closures, sporadic lockdowns, and social distancing measures – will likely have to confront unprecedented coronavirus fatalities if they are to ever return to pre-pandemic life.

Herd immunity – the threshold at which widespread transmission ceases, which experts currently place at above 80 per cent of the population – is expected to remain out of reach for many jurisdictions due to vaccine hesitancy and the emergence of mutant virus strains. Even when that threshold can be reached, small, sporadic outbreaks are still likely to occur once governments ease border restrictions that kept the virus out, helping avoid the massive toll in North America and Europe, which have reported some 1.8 million deaths. Among the unvaccinated, small numbers of people will sicken and die. In rarer cases, some deaths will occur even among those who are fully vaccinated.

“With Covid-19 circulating, it will become just another cause of infectious disease, and possibly death, but for most, death and serious illness will be vaccine preventable,” said Catherine Bennett, a public health expert and epidemiologist at Deakin University in Melbourne.

While much of the world has been exposed to mass death and disease during the pandemic to the point of desensitisation, many Asia-Pacific economies have kept death rates below that of a typical flu season. Down the track, that leaves them facing uncomfortable decisions that authorities appear unwilling to discuss or even acknowledge out loud. Unless they remain cut off from the world indefinitely, even as North America and Europe restart travel and learn to live with the virus, societies that avoided the worst of the pandemic will ultimately have to reassess their tolerance for death.

Tables are cordoned off at a hawker centre in Singapore, which in May

tightened Covid-19 restrictions following a rise in cases.

Tables are cordoned off at a hawker centre in Singapore, which in May

tightened Covid-19 restrictions following a rise in cases.

“It is going to be difficult to refocus and see the big picture because people have been terrorised into myopically focusing on Covid-19 deaths,” said Julian Savulescu, a philosopher and bioethicist based between the University of Oxford and University of Melbourne. “There has been little or no honest discussion about the value of life, how much we should spend to save a life, how we should consider length and quality of life, of risk for specific groups, of the value of liberty and the costs in terms of other lives and well-being of the policies adopted.”

Nancy Jecker, a bioethics professor at the University of Washington who serves as an adviser to the Centre for Bioethics at Chinese University of Hong Kong, said societies needed to have an open discussion about acceptable levels of death and disease.

“It would be helpful if we clarified our values about risk by speaking more directly about this in our families and communities,” she said. “It would also be helpful if government leaders and public figures modelled this.”

VACCINE COVERAGE CLUES

It is uncertain how many Covid-19 deaths societies can expect once vaccination drives have reached their peak, although some public health experts believe that with high enough vaccine coverage, fatalities could be reduced to levels comparable to seasonal flu.

Countries that have already achieved high vaccine coverage – such as the United States, Israeland Britain– offer some clues. In the US, where about 63 per cent of adults have received at least one dose, there was an average of 361 deaths each day during the week ending June 13. In Britain, where three-quarters of the population have received one dose but cases are on the rise due to the spread of the Delta variant first identified in India, there were on average nine deaths over the same period. Israel, which has administered a first dose to about 63 per cent of the population, recorded an average of two deaths each day.

Although all three countries have seen deaths fall dramatically since the peak of the pandemic, their Covid-19 mortality rates remain well above those seen in Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Singapore or Vietnam – five jurisdictions where a total of around 1,240 people have died, and fatalities are rare enough to make headline news.

Australia and Hong Kong have ramped up their vaccine roll-outs in recent weeks after sluggish starts, with more than 20 per cent of people receiving at least a single dose. New Zealand has administered at least one dose to about 10 per cent of the population, while Vietnam, which has struggled with serious supply shortages, has reached less than 2 per cent of its citizens. Singapore, which has had one of the fastest roll-outs in the region, has administered a single dose to nearly 45 per cent of its population.

In a sobering analysis that raised questions about Australia’s prospects for returning to pre-pandemic normality, Margaret Hellard, director of the Melbourne-based Burnet Institute, last week said authorities might need to intermittently “reintroduce public health measures and restrictions to control outbreaks” even with high vaccine coverage.

Yet societies tolerated much higher tolls from the flu before the pandemic.

In New Zealand, where just 26 people have died of Covid-19, researchers at the University of Otago in 2017 estimated that the country experienced about 500 flu deaths every year. In Hong Kong, which has reported 210 deaths from the disease, a 2004 paper published in the Clinical Infectious Diseases journal found that more than 1,000 people died of flu-related illness annually.

Charles Kenny, a senior fellow at the Centre for Global Development in Washington and author of the book The Plague Cycle, said he believed zero-Covid-19 economies could aim for even lower death rates than those associated with the flu given the effectiveness of the vaccines, especially if high vaccination rates were achieved worldwide.

“They start in a strong position, in that they’ve been world leaders in the response so far,” Kenny said. “I hope they deserve their citizens’ trust that they’ll continue being so competent, because if they do Covid-19 will be very far down the rankings in terms of infectious death and disability.”

The Burnet Institute last week estimated that without pandemic measures, including lockdowns, the Australia state of Victoria – home to about a fifth of the country’s population of 25 million – would see 4,885 deaths if the virus entered the community at 60 per cent vaccine coverage, and 1,346 deaths at 95 per cent coverage. Either figure would be far higher than the official toll of Australia’s 2017 flu season, the most lethal on record, when 1,255 people died across the country.

Within the zero-Covid-19 club, authorities have offered few specifics when it comes to the level of disease and death they would be willing to accept to reopen to the world – although as conditions improve, they have raised the possibility of piecemeal adjustments to border controls, such as travel bubbles and reduced quarantine for vaccinated travellers from low-risk jurisdictions.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who has flagged keeping borders shut until at least mid-2022, has vowed not to ease restrictions on travel until it is “safe”. Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has indicated that a high vaccination rate, along with other disease control measures, would be “beneficial to the reopening of borders”, although people’s safety would come first.

WHAT DOES ‘SAFE’ MEAN?

Seeking greater clarity about zero-Covid-19 exit strategies, including trying to define what subjective terms such as “safe” precisely mean, has proved a perilous task for those who have dared to try.

Last month, Virgin Australia CEO Jayne Hrdlicka faced boycott calls and an avalanche of criticism, including from the prime minister, after she suggested Australia’s borders should reopen once enough people had been vaccinated even though “some people may die”.

Bennett, the Deakin University epidemiologist, said that rather than targeting a specific number of acceptable deaths, societies should learn to view Covid-19 as “one of the possible infectious contributors to our death numbers”.

“Our elderly will succumb to pneumonia, flu or Covid-19, or any other number of conditions,” she said. “We should not be reporting just Covid-19 deaths on a daily basis.”

A woman in Hanoi walks past a sign that reads “Preventing and fighting

against COVID-19 pandemic is protecting yourself, your family and

society”.

A woman in Hanoi walks past a sign that reads “Preventing and fighting

against COVID-19 pandemic is protecting yourself, your family and

society”.

Savulescu, the University of Oxford bioethicist, said one way to approach the issue of determining a reasonable disease burden would be to take a “fair innings” approach that did not count deaths after a certain age.

“Personally, I think it is wrong to count the death of an 80 year old who is vegetative from dementia as the same as a fit, healthy 40 year old who has a young family,” he said. “But they are counted the same by governments all around the world. So I don’t think it is just numbers of deaths that matter but the length and quality of life that is lost.”

Although attempting to measure the value of human life may appear both callous and complicated, governments in fact often do just that when determining whether regulatory policies and medical treatments are worth the cost.

The World Health Organization considers a treatment to be cost effective if it is priced at less than three times an economy’s GDP per capita for every one year of good health it provides – a measure known as “quality-adjusted life year”.

Authorities also use a measure called value of a statistical life, also known as VOSL, to quantify the economic benefit of saving one human life. In Hong Kong, a government review into air quality standards in 2019 put the value of one life in the city at HK$18 million.

Jecker, the University of Washington professor, said science alone could not answer questions about which strategies governments should pursue.

“These questions are inherently value questions,” she said. “Answering them depends on weighing values such as individual liberty, public health and safety, loss of life, and duties to those who are at most risk of becoming infected and dying.”

Hongkongers queue for a Covid-19 vaccination at the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Park Sports Centre.

Hongkongers queue for a Covid-19 vaccination at the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Park Sports Centre.

Roberto Bruzzone, co-director of the HKU-Pasteur Research Pole in Hong Kong, criticised the lack of “rational” discussion about acceptable risk during the pandemic.

“We are all mortal but seem to have forgotten this simple truth,” he said. “Society should have a comprehensive discourse to explain this crisis and move on: we cannot keep publishing this daily war bulletin of numbers of cases and deaths per country.”

Bruzzone said an “acceptable burden of disease” in his opinion was one that the health system was capable of dealing with without becoming overwhelmed.

“We should discuss this, give these numbers, talk about how many people have died of flu in Hong Kong and of car accidents, and of community-acquired pneumonia,” he said, adding that governments should set a timetable for reopening their borders. “If people do not want to get vaccinated, it is their choice, but if a government endorses and recommends vaccination, then those who do not comply should not influence public health policies.”

Calvin Ho, an expert in medical law and ethics at the University of Hong Kong, said it was difficult for authorities to set clear thresholds during a fluid pandemic situation, but it was important to engage with the public about what the future should look like.

“The expectation is that Covid-19 will eventually become more flu-like, and should at that point be treated like flu,” he said. “From an ethical standpoint, it is important for governments to engage their constituents in meaningful dialogue on how a return to normality could come about, being mindful of what additional burdens the health systems could bear.”

Ho said he believed neither the Hong Kong government nor the public thought Covid-19 could be avoided forever.

“The expectation may instead be for Covid-19 to eventually become flu-like, or perhaps peter out – like Sars [severe acute respiratory syndrome] – so current inconveniences are simply tolerated,” he said.