Nicola Fan hopes her short film ‘Daffodil’, about a woman’s struggle as she comes to terms with the suicide of her estranged mother, will help people open up about their own issues.

Indieflix, a global streaming platform for social-impact films, recently added Hong Kong director Nicola Fan’s Daffodil to its collection, making the 18-minute short film – an exploration of a young woman’s internal struggle as she comes to terms with the suicide of her estranged mother – available to a much wider audience.

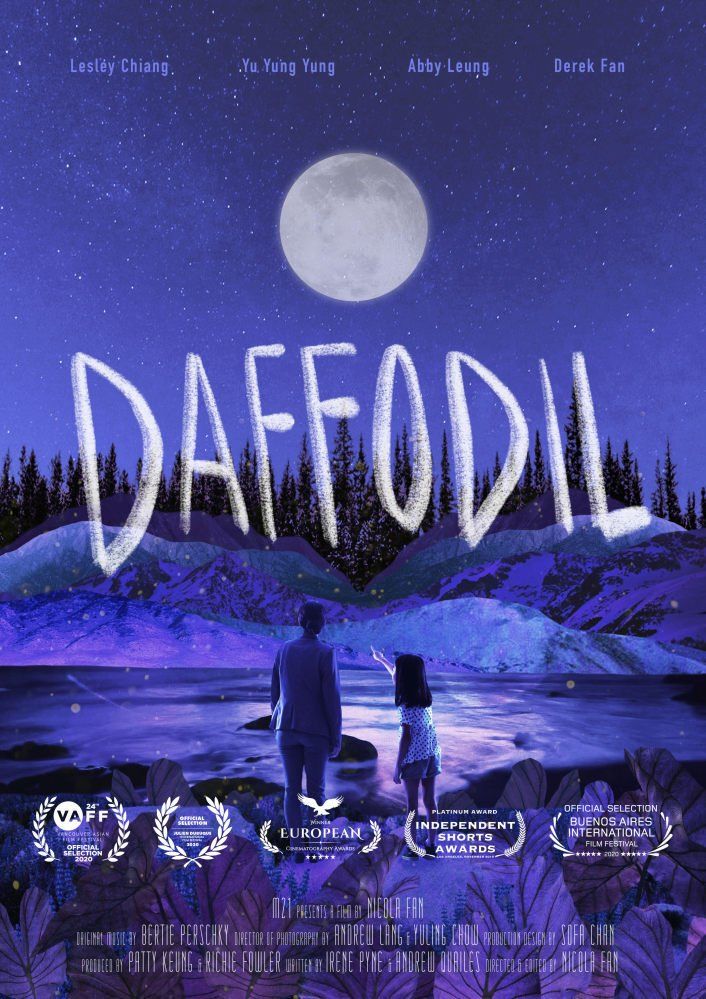

Daffodil picked up a string of awards following its release just before the coronavirus pandemic, including best short film cinematography at the 2019 European Cinematography Awards, and was in the official selection for the 2020 Vancouver Asian Film Festival.

“It’s a story of how loss forces us to realise what we have, retune our mindset and thinking, and make active changes for the better,” Fan, 32, says.

Covid-19 restrictions stopped the many scheduled public screenings but viewers can now watch it online (sign up to Indieflix’s seven-day free trial to watch it for free).

In Daffodil, the central character, Mia, grows up learning to work around and adapt to her mother’s often turbulent behaviour without understanding the mental health issues that are causing it. We then see how that childhood informs her adult self. The story is loosely based on a close friend of Fan’s whose mother committed suicide when they were university students. In the aftermath of the tragedy, her friend became reclusive and didn’t talk to his family.

Nicola Fan (right) on the set of Daffodil.

Nicola Fan (right) on the set of Daffodil.

“In Asia, especially my parents’ generation, we often don’t talk about mental health,” Fan says. “For my parents’ generation, it’s all about surviving the day-to-day – they don’t have time to think about whether they are happy, or whether life is meaningful. In my generation, it’s more about opening up and sharing stories and experiences, which means you are not alone.”

But the stigma around mental health in Asian culture is shifting, says Dr Elisabeth Wong, a psychiatrist and adviser at mental health charity Mind HK.

“I do sense there is less restriction in Hong Kong and it’s easier to talk about mental health these days,” she says.

The high-profile suicides of pop stars Leslie Cheung in 2003 and Ellen Loo in 2018 broke open public debate about the issue, Wong says. Meanwhile, education and destigmatisation programmes such as StoryTaler, which invites people with experience of mental health challenges to share their story, have helped change the narrative.

“People don’t feel they can validate their own experience until they can see it – whether it’s in films, novels or songs, these more public interfaces – and then they can put a name on what they are feeling and validate it,” Wong says.

Daffodil poster.

Daffodil poster.

Fan hopes her film will make it easier for people to open up and have honest conversations. Immediately after private screenings of the film, audience members came up to her privately and shared very personal stories, she says.

“I see film as a great medium to dive into topics that are often too hard or too awkward to start with friends,” she says. “It’s easier then to talk about how to make changes and move on from there.”

She says that as a university student she did her best to support her friend who lost his mother, but now that she’s older, she has learned to be less intimidated about starting a conversation about mental health.

“If it’s a close friend, it’s important to reach out from time to time to see how they are doing,” she says. “Keep it light and let them know you are there for them whenever they need. It doesn’t have to be about meeting up and talking about it, you could suggest a swim or a hike, something to take their mind off it. Something active can be beneficial.”

Everyone processes trauma differently, Wong says, so it’s important to leave it to the person to set their own pace. If you want to help someone, first check in with yourself and make sure you have the emotional and physical capacity to help. If so, let them know you are there if they need you.

“Don’t just go in once, check in from time to time. In the initial phase of trauma, people can cope quite well – perhaps because of denial, or the trauma may not have set in. It’s after the initial stage when the emotions start to come in,” Wong says.

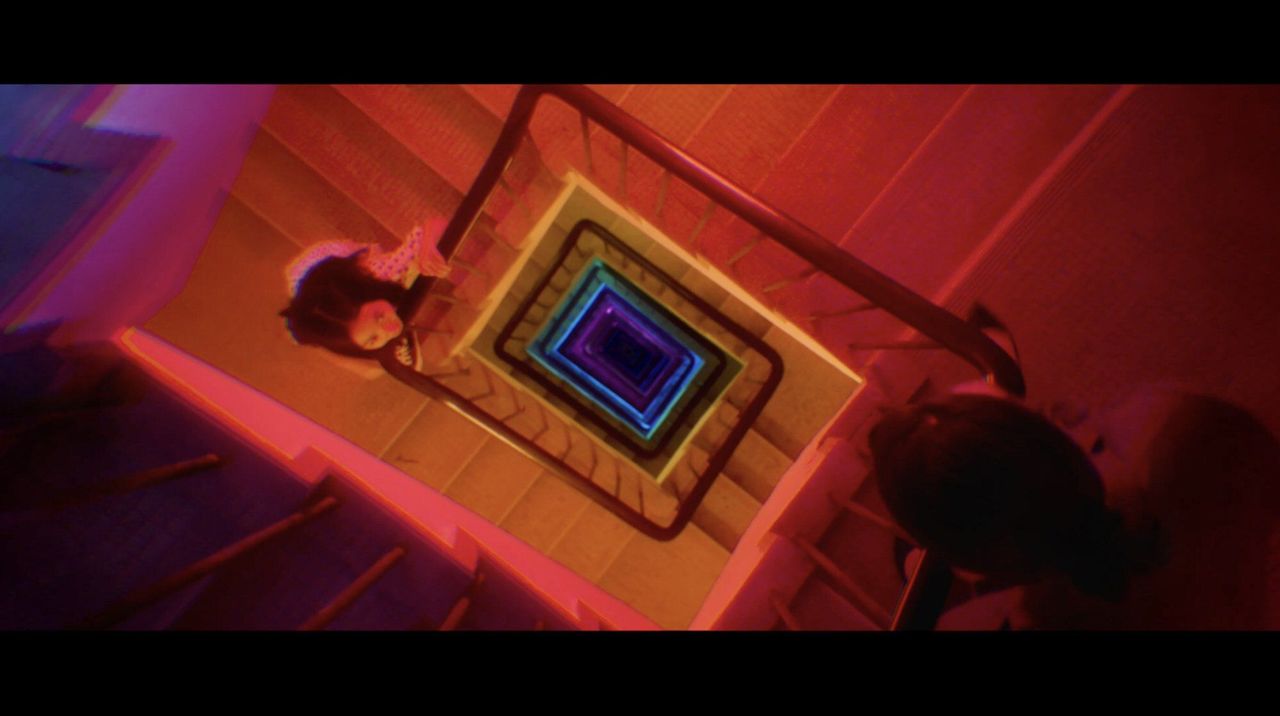

A scene from Daffodil.

A scene from Daffodil.

If the person is ready to talk, Wong advises choosing a time and place where you won’t be disturbed – and really listen to them.

“There is no need to paraphrase or guide, just listen. It is already very therapeutic if you can provide your whole presence with listening,” Wong says.

If you don’t understand what the person is going through or know the right course of action, then acknowledge that. Admitting to having limitations is a healthy way of supporting your friend, Wong says. Then seek professional help for them if necessary, perhaps making the call to a clinic and going with them to their first appointment.

A scene from Daffodil.

A scene from Daffodil.

For many, the pandemic has been a time to turn inward, to spend more time in self-reflection. Fan hopes that Daffodil will open a door for those looking to have more meaningful conversations and connections.

“If we all understand we are not alone, that’s the key,” she says. “Hopefully, this film can help those who have experienced this realise there is focus and attention on this. We are all learning to be more open to everyone’s trauma, especially now that, globally and collectively, we’ve all experienced loss through traumatic changes.”