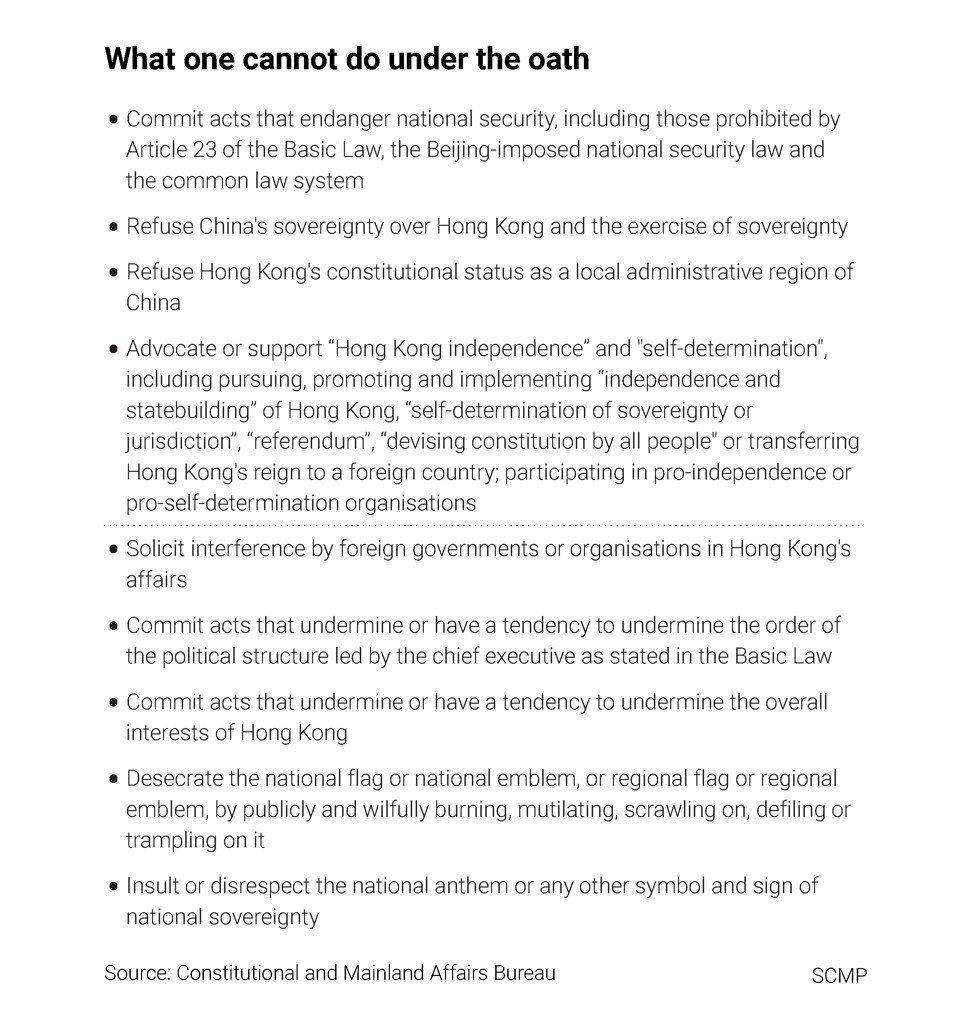

Experts say the bill’s ill-defined terminology gives the government too much leeway in deciding what kind of behaviour is and is not acceptable.

Vague language in a proposed bill aimed at ensuring the allegiance of public office holders would grant Hong Kong authorities broad powers to disqualify those deemed insufficiently patriotic, and would give Beijing another avenue for quashing dissent in the city, legal experts have warned.

The experts took issue with a raft of political concepts peppered throughout the legislation – dubbed the Public Offices (Candidacy and Taking Up Offices) (Miscellaneous Amendments) Bill 2021, unveiled on Tuesday – saying they lacked clear legal definitions, deviating from the principle of certainty under the city’s common law system.

One particular item of concern, for instance, was the provision that public office holders could be disqualified for doing something viewed as having “a tendency to undermine” the interests of Hong Kong, they noted.

“Everything is capable of being interpreted by the Hong Kong and Chinese governments to ‘have a tendency’ to undermine Hong Kong’s overall interests, such as, for example, expressing caution about the Sinovac vaccine,” said Phil Chan Ching-wai, a human rights law scholar based in Britain, referring to the mainland-made Covid-19 jabs which some local activists had urged people to boycott.

Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang (centre)

unveils a new draft law on oath-taking for public officials on Tuesday.

Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang (centre)

unveils a new draft law on oath-taking for public officials on Tuesday.

Organising a protest might also cross the red line, Chan said, cautioning against such a vague choice of wording, which he said went against the city’s tradition of drafting clear and strictly defined laws.

Principal law lecturer Eric Cheung Tat-ming, of the University of Hong Kong, noted the bill also forbade advocacy of political ideas such as “self-determination” and “referendums”. However, it did not define those notions, he continued, likening the laws to ones across the border, which tended to be more vaguely worded, leaving more room for interpretation by the authorities.

The proposed legislation seeks to consolidate all oath-taking requirements the central government has laid out over the past five years. Its announcement came amid a stepped-up campaign by Beijing to weed out members of the city’s district councils, legislature, government and judiciary deemed “unpatriotic” following a landslide win by the opposition camp in 2019’s local elections.

Professor Jerome Cohen, director of New York University’s US-Asia Law Institute, said the draft legislation would not comply with international standards.

“Most ominous is its intended application to the judiciary in order to assure that judges will be sufficiently ‘patriotic’ to continue to exercise their independent powers,” he said.

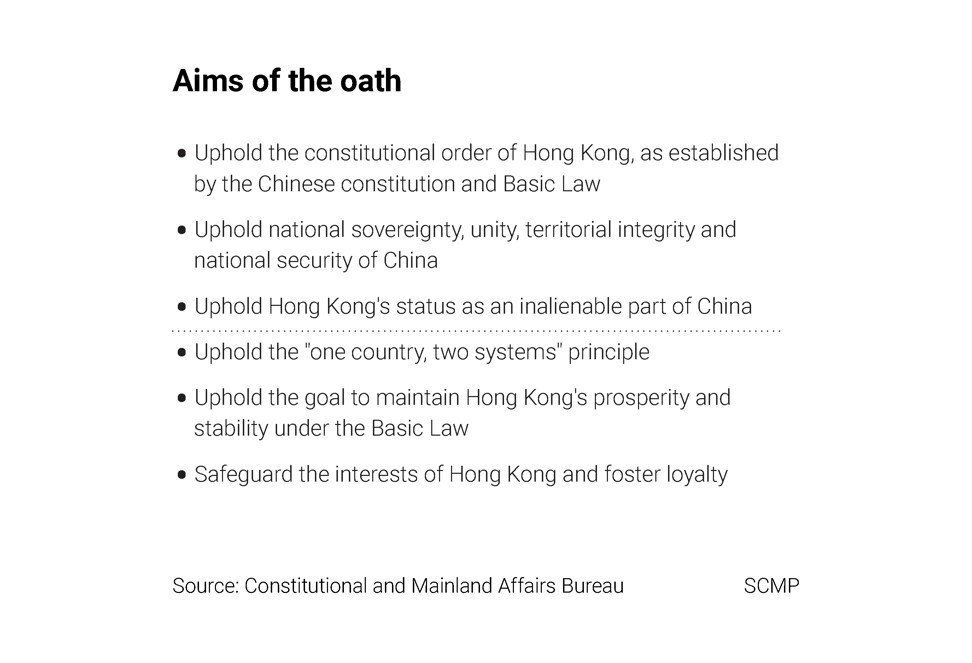

The new law would impose a five-year election ban on those disqualified from office. It also contains “positive and negative lists”, setting out what acts are, and are not, regarded as upholding the Basic Law and bearing allegiance.

According to the lists, a public officer should uphold the city’s constitutional order, for instance, but should not commit acts that endanger national security or “undermine, or have a tendency to undermine the overall interests of Hong Kong”.

Albert Chen Hung-yee, a Basic Law Committee member, maintained the new bill was actually more detailed than the red lines drawn by Beijing in the past.

“Ambiguities are bound to arise in any legal provision and that’s why people rely on litigation in courts to solve disputes,” said Chen, who also specialises in constitutional and mainland law at HKU.

He acknowledged that the bill was drafted in such a way as to avoid a repeat of the “35-plus plan”, which called for the opposition winning a majority in the Legislative Council, enabling it to block the passage of the city’s budget and force the resignation of the chief executive.

The plan never came close to fruition, with the government postponing the Legco elections by at least a year, but an unofficial opposition primary was held to select candidates to run for office.

The authorities subsequently labelled the scheme subversive, and arrested 55 primary organisers and candidates in January.

Lau Siu-kai, vice-chairman of the semi-official mainland think tank the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, argued that, in fact, the new law should have been even more vague so as not to constrain the government in the event the opposition found new ways to get around it.

However, he speculated that the law might not be widely enforced, as it was more an example of Beijing playing political hardball to put opposition members, specifically those who now dominate the city’s district councils, on the back foot.

“The ball is now back in their court,” he said, adding that councillors would now face the dilemma of either refusing to comply with the new oath requirements and being disqualified, or accepting them and dealing with backlash from their supporters.

Expressing concerns over the use of vague language in the bill, Civic Party chairman Alan Leong Kah-kit, a senior counsel by trade, said he feared the worst-case scenario would be that even the most conventional pan-democrats would be barred from standing for elections in the future.

Three lawmakers from his party were already disqualified last year following a resolution from Beijing allowing for the ousting of Hong Kong legislators deemed to have promoted independence, encouraged foreign interference or engaged in acts threatening national security.

Leong pointed to a recent speech by Xia Baolong, the head of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, emphasising the importance of Beijing’s principle of only “patriots governing Hong Kong”.

Whether Hong Kong authorities would use the proposed law indiscriminately to achieve that aim, he said, “is all up to the Central People’s Government”.