First local case was recorded in January 2020, and since then, city has weathered four waves of infections, each with its own challenges.

On the last day of 2019, health minister Sophia Chan Siu-chee received an ominous call from Hong Kong’s top infectious disease expert Professor Yuen Kwok-yung. It was a call Chan would never forget. Yuen’s message? A novel virus outbreak had emerged in Wuhan.

The world would soon experience its deadliest pandemic in more than a century, on a scale not seen since the Spanish flu in 1918. On Saturday, global Covid-19 infections approach 100 million, with deaths in excess of 2 million.

As Chan hung up the phone, her mind turned to preparing the city for an emergency response and containing the virus. Within days, the government drew up contingency plans for hospitalisation and quarantine.

Then on January 22 last year, two tourists from Wuhan were declared as suspected coronavirus patients. A day later, their infections were confirmed, becoming the first Covid-19 patients in the city. At the time the disease was not yet named.

“I have had a wartime mentality since December 31, 2019,” the health secretary said in an interview with the Post. “We have always been very proactive in terms of preparing for the epidemic, even when the virus had not even arrived in Hong Kong.”

From her suite of offices overlooking Victoria Harbour in the east wing of government headquarters, the former nurse and university professor has led the battle against the unrelenting virus for a year.

Politically, the unforgiving war has not only tested the minister’s abilities to breaking point and even raised doubts about her suitability for the job, but it will also define the administration’s legacy in years to come.

In terms of public health, Hong Kong has gone from a “shining city upon a hill” in controlling the virus and a world leader in universal mask-wearing, to four successive waves of the coronavirus amid a late and rocky start in mass vaccination.

One year on, many are asking, has Hong Kong run out of luck?

A roller-coaster ride

Hong Kong’s year battling Covid-19 has been a roller-coaster ride, as the initial threat of imported transmissions from Wuhan subsided following border shutdowns in mainland China and the city.

But a new devil soon surfaced in the form of a coronavirus-stricken cruise liner stranded in Japan, presenting the challenge of repatriating residents among the vessel’s passengers.

In mid-March, as the virus began its rampage across continents, fearful Hongkongers working and studying in Europe and North America scrambled to return home, sparking off a second wave of infections that spread across bars and entertainment venues, as well as at a Buddhist worship hall in the city.

Local life largely returned to normal from April and Hong Kong seemingly enjoyed a lull in infections, when in fact, the virus had been lurking in the dark. Research showed sea and aircrew members given quarantine exemptions had brought in a new, faster-spreading strain of the pathogen.

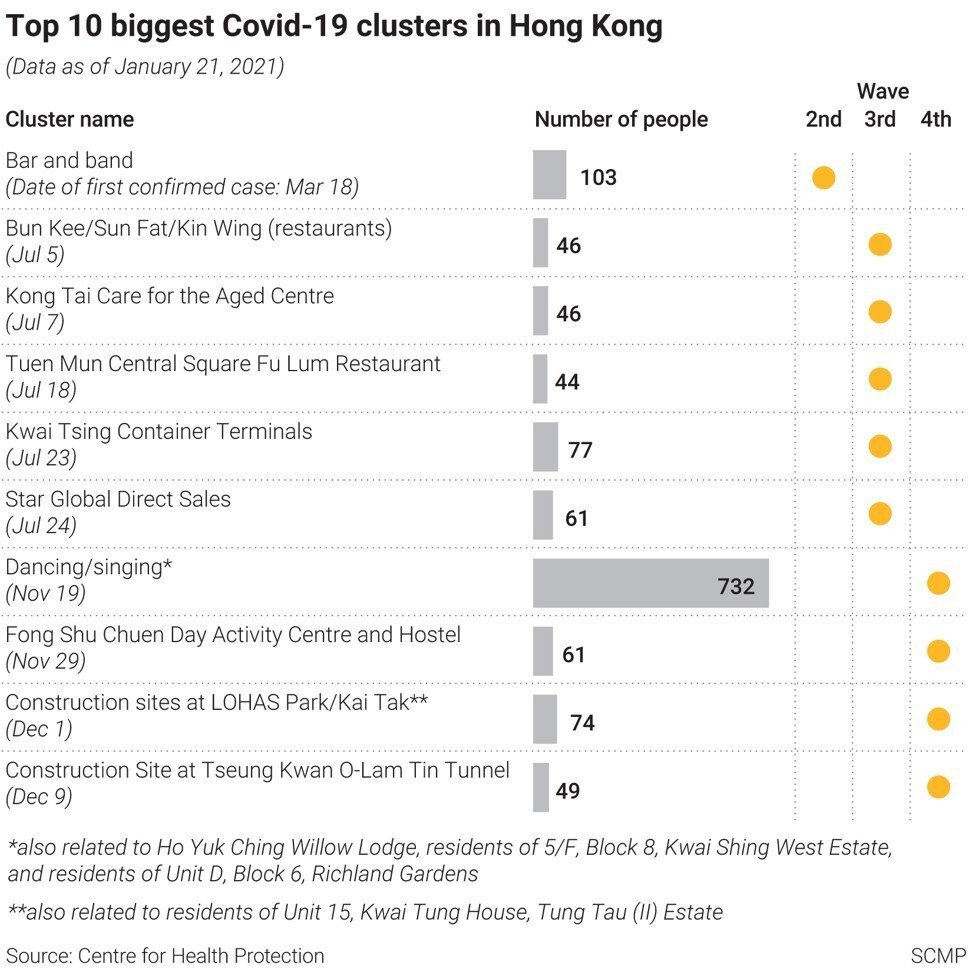

In July, Covid-19 once again reared its ugly head, with the city recording its highest mark of infections in a day, at 149. This time, the disease also struck multiple institutions hitherto untouched by the virus, including care homes for the elderly and disabled, hospitals and a container terminal.

Weeks after Hongkongers breathed a sigh of relief when the third wave abated in September, the enemy returned in force in late November, advancing almost unchecked across a swathe of 28 dancing and singing venues, and infecting 732 people in the largest Covid-19 cluster to date.

The new round of infections also derailed plans for a travel bubble with Singapore just a day before it was slated to launch.

The ongoing fourth wave threatens to be the longest round recorded in the city, lasting 66 days and counting. Despite dropping below 100 infections a day and hovering between 25 and 60 for a week or two, the wave has surged again in recent days and hit several old neighbourhoods hard.

‘Worst in China except Wuhan’

As of Saturday morning, the city had recorded close to 10,000 infections, with 168 related deaths.

Hong Kong’s record of dealing with the coronavirus is a mixed one, as far as Professor Gabriel Leung is concerned. The dean of the University of Hong Kong’s faculty of medicine served a stint about a decade ago in the administration as undersecretary for food and health, and oversaw the fight against swine flu in 2009.

The epidemiologist returned to the heart of government last year to shape the city’s anti-pandemic strategy, when he was tapped by Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, to be her top Covid-19 adviser along with three other experts.

“Hong Kong’s performance last year was not the best or the worst in the world,” he said. “Overall, it’s reasonably good, but it is the worst in China except Wuhan if you just look at the numbers.”

It is a view largely shared by the health minister, too. Chan described the city’s response as “not the most outstanding” among the cross-strait regions of Macau, Taiwan and mainland China.

Her defence was one she had trotted out many times before – that the crisis was a fast-moving creature, and the city learned from its mistakes. “The epidemic is not static,” Chan said. “When it evolves, every time we have more information, when we have better experience and more capacity, then we can actually respond and put in more response measures.”

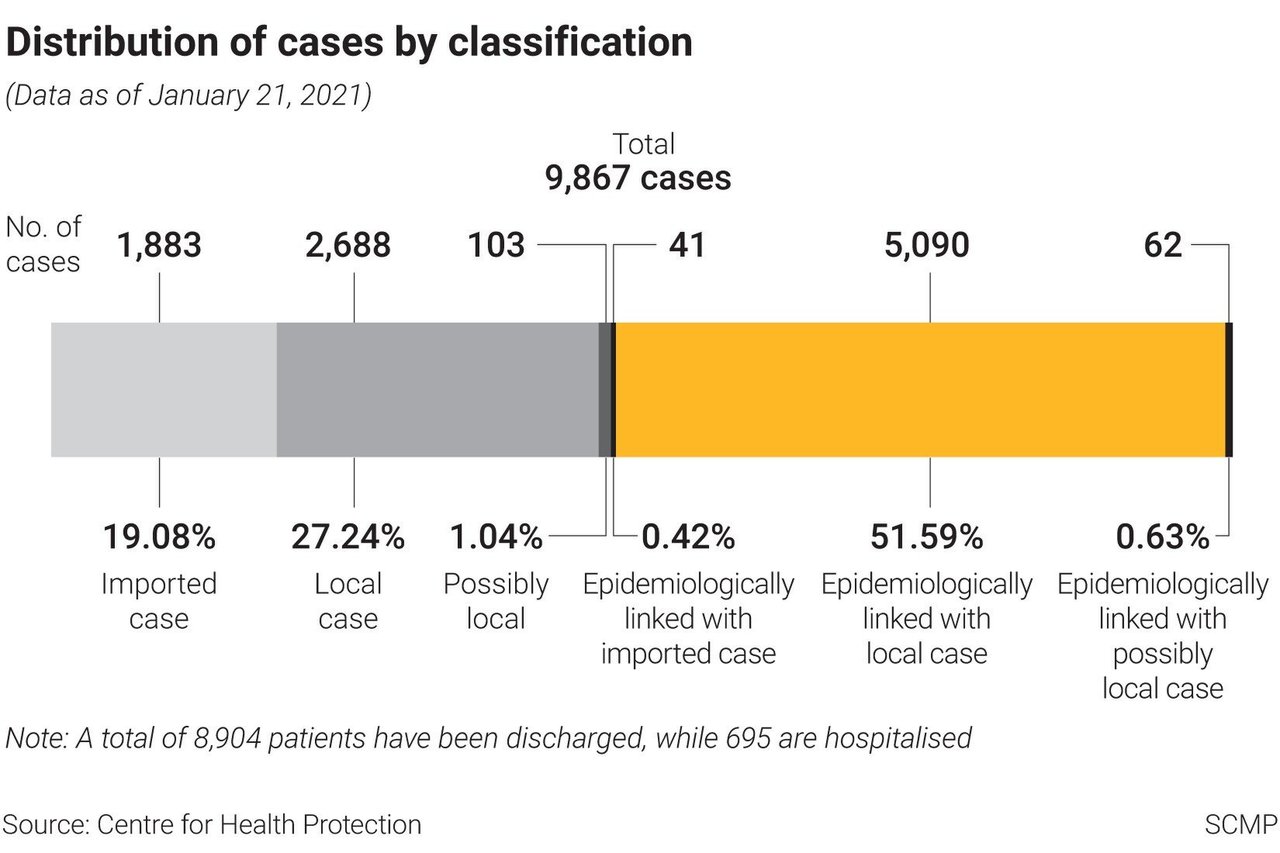

According to a Post review of all 9,867 Covid-19 cases as of Thursday, imported infections took up 19 per cent at 1,883, local transmissions accounted for 27 per cent (2,688 cases), while close to 52 per cent involved cases that had links with other local infections (5,090 cases).

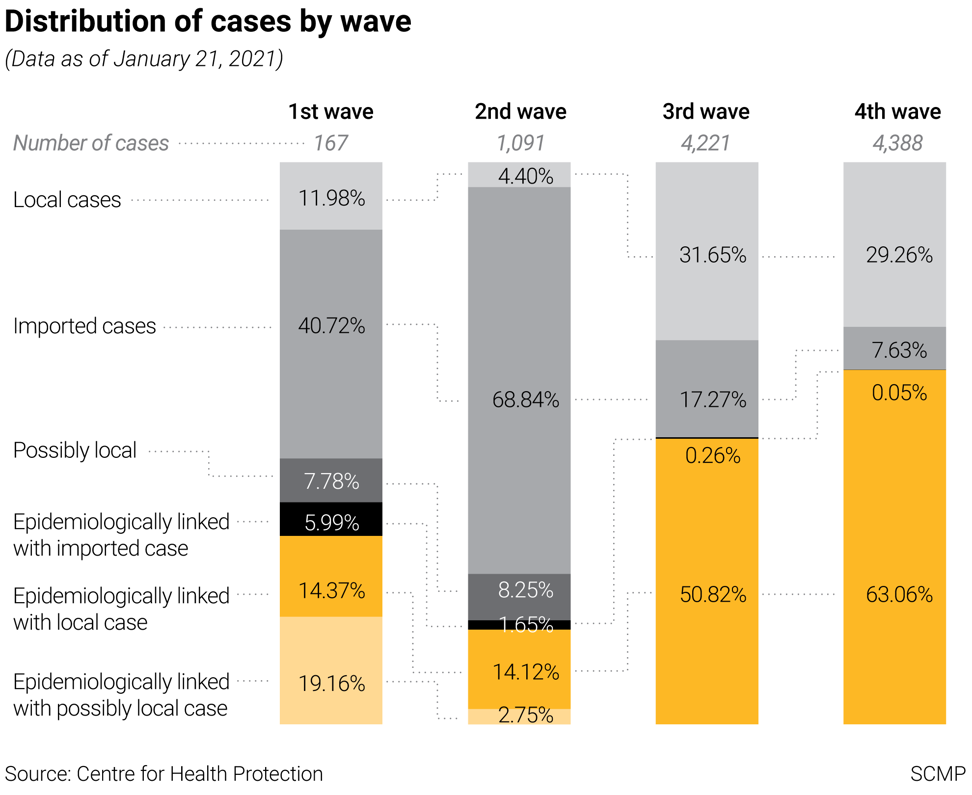

The proportion of imported infections hit a high in the second wave, representing nearly 69 per cent of all cases in that period, but steadily dropped afterwards, following the tightening of border restrictions.

Officials progressively stepped up border measures, with mandatory quarantine for all arrivals and the existing ban on all non-residents, imposed in March. The tightest restrictions landed recently with a ban on flights from Britain, after a new and far more transmissible variant of the virus was reported there.

On top of that, city residents woke up on Christmas to an extended quarantine for all arrivals – to 21 days from the initial 14 – at designated hotels.

The proportion of local cases, meanwhile, has also risen from 12 per cent in the first wave, to nearly 31 in the third, and 29 so far in the current round, despite the harshest curbs so far.

Throughout the pandemic, local measures aiming to stem the spread of the virus have ebbed and flowed, from the now-familiar drill of closure of leisure venues such as cinemas, karaoke lounges and bars, to a cap on the size of public gatherings, which was once relaxed to 50 people but is now at its most stringent at two.

Dine-in services were at one point banned entirely, but the decision was reversed just days later in an embarrassing U-turn for the government following a fierce public backlash, not least from blue collar workers who were seen having to eat their meals from lunchboxes on the roadside or, for cabbies, in their taxis. Currently, evening dine-in services are banned after 6pm.

Social-distancing fatigue?

Also in an unprecedented move, the government has issued emergency decrees almost on a weekly basis, and has increased its powers vastly, from ordering residents and recent visitors in a block to undergo mandatory testing, to locking down an entire area for screening.

Adviser Gabriel Leung expressed concern that public fatigue with social distancing would erode the effectiveness of measures.

“It does appear that the measures have got tougher and tougher, but their effectiveness has been declining,” he said.

While Hong Kong has prided itself on keeping Covid-19 infections at bay compared to the rest of the world, the coronavirus has ultimately crept into facilities such as hospitals and care homes, where residents with existing conditions are most at risk.

Asked whether the city’s record of protecting these institutions had been tarnished, Hospital Authority chief executive Dr Tony Ko Pat-sing said it was a “cumulative risk”.

“No matter how good a goalkeeper is, the ball will still hit the net if you keep shooting,” he said.

Ko has been at the helm of public hospitals for more than a year, but he still recalls his time as an internal medicine doctor in the fight against the severe acute respiratory syndrome, another deadly epidemic that hit the city in 2003.

He said protecting workers was his priority, adding authorities had stepped up infection control measures at hospitals, such as regular testing for high-risk staff, following the city’s largest Covid-19 outbreak to date, at United Christian Hospital where 21 patients and staff members have been infected.

Ko also defended the treatment of coronavirus patients, despite 168 deaths out of nearly 10,000 infections to date. Singapore, the Asian city state with a comparable population and demographics, has logged more than 59,000 cases but only 29 deaths.

The hospital chief said he believed Hong Kong’s usage of a cocktail therapy was sound, centred on a combination of antiviral drugs such as: interferon; Kaletra, a drug originally used for HIV/Aids; and Ribavirin, also used for hepatitis C.

Ko pointed out that most of the Covid-19 deaths in Hong Kong involved elderly care home residents, who were highly vulnerable to the virus and might have pre-existing illnesses. Singapore, by contrast, has had a massive wave of infections affecting mostly young migrant workers living in crowded dormitories.

A ‘general who can call the shots’

To Leung, the problem with the government’s response to the pandemic was structural, and stemmed from a lack of coordination between departments.

“Each department should take more responsibility in epidemic control within sectors and industries under them. It shouldn’t be the Food and Health Bureau doing all the heavy lifting,” the former government official said.

For instance, he noted, the Development Bureau should conduct weekly testing for builders before they were allowed to work at construction sites, where cases have been linked to a community spread in Yau Tsim Mong district in recent days.

A reason for the lack of collaboration, Leung said, was that those departments were afraid of a backlash from their members and stakeholders.

Another problem came from the chain of command and the absence of a “general who can call the shots”.

“Carrie Lam presides over the steering committee, directing overall policy, but she can’t be the one determining each implementation detail,” he said.

A 24-hour command centre, set up for typhoons and which existed annually in the east wing basement of the old government headquarters at Justice Place during Leung’s time in the civil service, should be created for this pandemic, he added.

“If we can have that for every typhoon to get a clear view of what is going on in each district, we should have that for the once-in-a-century pandemic too,” he said.

The government’s anti-pandemic communication and messaging have also come under fire. The slogan “coexistence with the virus”, underpinned by a “suppress-and-lift” policy that advocated a periodic tightening and relaxation of social distancing based on infection levels, was all but dropped from the health minister’s recent press conferences and public briefings.

In its place came a new emphasis on “sparing no effort in achieving zero infection”, a term frequently used by mainland officials and local politicians in the pro-Beijing camp. In recent months, the government has also adopted near-identical policies used on the mainland, such as a two-week universal community testing programme in September and more recently, mandatory screening for specific coronavirus-hit districts and buildings.

In the interview, however, Chan dismissed suggestions that officials were acting under pressure from Beijing to align their policies. “It is not a matter of pressure,” Chan said. “There are some places doing better in the world, and we ought to learn from them. There are some role models we should follow.”

She also defended how authorities had stayed firm on control strategies, and said the ideas of coexistence with the virus and achieving zero infection were “not mutually exclusive”.

“Coexisting with the virus doesn’t mean not striving for zero infections, or not trying our best to control it and letting the virus float around,” Chan said. “It describes a phenomenon … before an effective vaccine is available, the virus will still be around.”

If there was one charge the minister was prepared to plead guilty to, it was that the government had sometimes been slow in telling the public what it was doing, when policies were still on the drawing board.

Chan’s critics have argued she is out of her depth and ill-suited for the position as a leader in times of crisis. Calls for her to step down have only got louder, with even the pro-establishment camp joining the chorus, as Hong Kong passed its one-year mark fighting Covid-19.

The health minister has insisted on her diligence, telling the press she sometimes slept with her phone in her hand.

Asked if she had thought about throwing in the towel, Chan said she would soldier on.

“We have always been listening to comments and also criticism,” she said. “I will continue to do my very best to lead the Food and Health Bureau, the Department of Health and the Hospital Authority.”