Experts say technology exists to align Covid-19 protocols with the mainland, but privacy fears and a sceptical public are stumbling blocks.

Decoding the demands of mainland Chinese authorities before the border with Hong Kong can reopen appears to have become a big guessing game for ordinary residents and bureaucrats alike.

One key stumbling block has been the issue of the adoption of health codes that could aid detection and prevention of the spread of the coronavirus.

Hong Kong has the technological prowess to launch a mainland-style, movement-tracking app for the border reopening, experts have said, but privacy concerns and public acceptance could emerge as major obstacles.

The mainland’s use of an app, the so-called health code, which can store the travel history of users and generate a colour-coded warning system based on exposure risks to Covid-19 patients, has become a sticking point in protracted talks between Chinese and Hong Kong authorities to resume quarantine-free travel.

“We let apps such as Google Map track our whereabouts every day. But whether people are willing to allow the Hong Kong government – let alone mainland authorities – to do that is a very different question,” said Francis Fong Po-kiu, honorary president of the Hong Kong Information Technology Federation.

Stephen Wong Kai-yi, the city’s privacy watchdog chief until last year, however urged for “mindset adjustments”, saying both mainland China and Hong Kong had adequate data protection laws to deal with private intrusion problems triggered by such apps.

“It is also a public interest issue and there is a pressing need to address these legitimate issues as expected by members of the public and authorities concerned,” the former privacy commissioner for personal data added, referring to demand for unfettered access to the mainland.

The first meeting of experts and officials between the two sides in late September chalked up little progress on reopening. Chief Secretary John Lee Ka-chiu returned home with the announcement that Hong Kong needed to improve on three broad areas, spanning screening requirements for inbound travellers, its quarantine system and the city’s overall approach to risk.

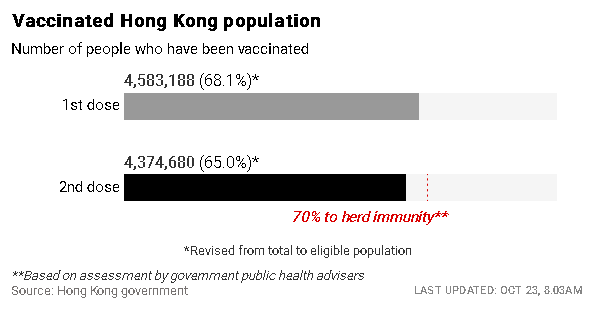

But with Hong Kong’s months-long “zero-Covid” streak in the community – barring a handful of cases involving airport workers – and an improving vaccination rate of 67.9 per cent, all eyes are now on the health app, a hot topic among officials themselves.

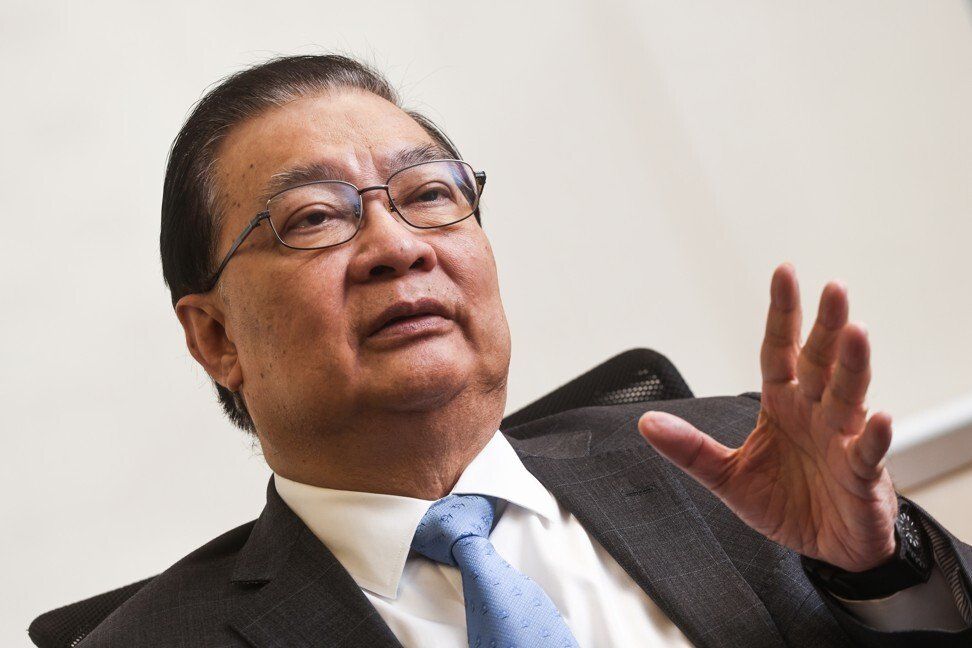

Last week, the issue of closed borders ratcheted up when pro-Beijing heavyweight Tam Yiu-chung revealed he was banned from attending a National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s meeting, which kicked off in Beijing on Tuesday, after mainland authorities cited the risk of infection posed by a single, untraceable coronavirus case recently found in Hong Kong. Tam is the city’s only member on China’s top legislative body.

Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to China’s top legislative body.

Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to China’s top legislative body.

A rare rift then opened up in the pro-establishment bloc when Tam warned the mainland was unlikely to accept any Covid-19 health code-sharing proposal unless Hongkongers submitted contact-tracing information, in a comment seen as a rebuke to innovation and technology secretary Alfred Sit Wing-hang’s various suggestions for the app, including a voluntary system.

How Hong Kong’s system differs from that of the mainland and Macau

The options for Hong Kong to ensure an appropriate health app that can get mainland authorities’ buy-in seem to be unclear for now. Sit said over the weekend that the government had submitted a number of proposals to state authorities on how a Hong Kong health code should work, for people to travel quarantine-free across the border.

He said options included allowing people to voluntarily declare their daily whereabouts and report whether they had visited any high-risk places, the proposal most likely to have triggered Tam into issuing the firm rebuttal. Sit added it was also possible technically to transfer records of users’ whereabouts from the city’s Covid-19 “Leave Home Safe” app to the health code, but maintained this would only be done if people agreed to it.

Hong Kong’s ‘Leave Home Safe’ app is voluntary.

Hong Kong’s ‘Leave Home Safe’ app is voluntary.

But how do these systems work in the first place?

Hong Kong launched “Leave Home Safe” last November. Billed as an exposure notification device, it allowed users to gain entry to various premises such as restaurants, bars and karaoke lounges, by scanning a QR code, thereby lodging a digital footprint with the app.

Users will receive a notification when a member of the public confirmed to be a Covid-19 patient also visited the same location. To calm a sceptical public, the government went to great lengths to explain it was a scheme of voluntary participation where visits were recorded at users’ discretion.

Officials were also at great pains to stress that it would not use positioning services or any other data from users’ mobile phones, while venue check-in data would be encrypted and saved only on personal devices for 31 days, without being uploaded to the government system or any other platforms.

By contrast, the broad idea of the health code system on the mainland is made up of two parts. One is the frequently cited health code, which indicates one’s Covid-19 risk status based on individual information such as residential address and any history of close contact with suspected patients.

Another component is the “itinerary code”, which tracks a user’s whereabouts with signalling data from the mobile phone. This code makes use of data from three major telecommunications companies on the mainland – China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile. It can show which countries or mainland cities a user has visited in the past 14 days. The code also captures user movements with precision and stores the information for use by the authorities.

All residents need to show both codes when entering large public venues such as restaurants, shopping malls and hospitals.

While there is only one version of the itinerary code on the mainland, the health code is highly fragmented as different provinces and cities had rushed to develop their own versions at the start of the pandemic, after the first one was launched in Zhejiang’s Hangzhou city in February 2020.

Subsequently, the health code idea was quickly adopted by other provinces and cities. In addition to the provincial health codes, more cities have also developed their own health codes, such as Guangzhou “Suikang Code”, Shenzhen’s “ShenyiYou”, Nanjing’s “Ningguilai”.

Most of the code systems are based on Call Detail Records data from telecoms companies and big data analysis, with some involving manual declaration.

The local health code systems across different regions are managed by various government departments and agencies. Beijing’s Municipal Bureau of Economics and Information Technology, Shanghai’s Big Data Centre, Shandong’s Provincial Health Commission and Liaoning’s Business Environment Bureau are in charge of the health code systems in their respective regions.

Cross-border travel between mainland China and Hong Kong has been reduced to a trickle during the pandemic.

Cross-border travel between mainland China and Hong Kong has been reduced to a trickle during the pandemic.

Macau – which has reopened borders with Guangdong and has often been cited as the model city Hong Kong should look to in putting forth a proper plan to resume travel with the mainland – has its own health code system. Its version is not a direct copy of the mainland’s health or itinerary code. Macau’s code does not have a tracking function, but generates coloured QR codes which indicate a person’s level of risk based on their health status, possible contact with Covid-19 patients and travel history. The QR code, updated daily, is required to be displayed when people enter large public venues.

It also allows users with negative test results to switch over to Guangdong’s health code system when they cross the border, but the two apps are not directly linked.

Lingering privacy and public acceptance concerns

Fong, of the IT federation in Hong Kong, said the technology was already there for the city to create a movement-tracking health code armed with a GPS capability, citing the location-sharing function across many apps used by residents such as Google Map, WhatsApp and even Apple Photos.

“It is not hard to set up an all-in-one platform containing a person’s negative Covid-19 test result, vaccination record, and the entry records at past locations,” he said. “But you may lose half of your users at once if you ask them to turn on real-time tracking by the government.”

Fong believed public acceptance would also vary, depending on the level of intrusion in the design. For instance, he said, an app that gave premise owners and border checkpoint officers the ability to scan and take away all your information would likely have fewer admirers than one that put the onus on users to record entry data on their phones.

And as long as there was consent from users, Fong said he believed that having those tracking data sent to the authorities or other jurisdictions would not be a problem.

Former privacy commissioner Wong said the city’s Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance “expressly excluded” the use or disclosure of information – including the identity and location or GPS footprints of an individual – which would likely have serious impact on the health of others.

In short, health emergencies affecting others would allow the disclosure of such data.

“The Covid-19 issue is about an individual’s right to life, which is an absolute right as opposed to a privacy right, which is a qualified one. Where there is a conflict between the two rights, the privacy right will have to give way to the right to life, albeit both are fundamental human rights,” Wong explained.

That said, Wong, who has since returned to private practice as a barrister, pointed out that as the matter concerned personal data, the general data protection principles specified in the ordinance would still have to be followed.

They included: obligations to “clearly inform” the individual concerned in a language that “a man or a woman in the streets of Mong Kok” would understand for the purpose of data collection; that there should not be collection of excessive data (data minimisation) and the erasing of data when it is not required; clear declaration that the usage or disclosure of data collected is for no other purposes; and with whom the data would be shared.

Authorities or organisations would also have to ensure adequate data security measures were taken on board and to provide a channel for the individual concerned to access and correct his or her own data collected, Wong said.

The former watchdog head however noted that since the passing of the mainland’s Personal Information Protection Law, which would take effect in November, the data protection statutory measures would become substantially similar to those of Hong Kong and the European Union, “if not more stringent”.

The stricter parts included “separate consent” being required before sensitive data can be transferred out to Hong Kong from the mainland. Wong said he therefore believed individuals concerned would be able to have the legal redress and remedies against any organisations or authorities should the laws be violated in the case of a health code.

Professor Lee Jyh-an, an information law specialist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, however struck a more cautious tone.

“While privacy laws in both Hong Kong and mainland China prohibit data processors from using personal data beyond legitimate purposes, there is no efficient dispute resolution mechanism for a Hong Kong citizen to claim his/her right in mainland China if data breach occurs there.”

Lee pointed out that although there had been several initiatives regarding the integration of dispute resolution mechanisms in the Greater Bay Area, there had not been any “relevant” dispute resolution cases to date concerning cross-border transfer of personal data.

Lee agreed that while the Hong Kong government could be exempted “under circumstances relevant to citizens’ health” from several data protection obligations, meaning it would not need consent from individuals to process their personal data, it did not mean that it can exchange personal data with other governments for public health purposes “without any limitation”.

“The government should still assure residents that its counterparty has acted reasonably to protect the personal data of Hong Kong people.”

While privacy and technology would no doubt feature heavily in the issues to be ironed out, at the end of the day, analysts said Hong Kong would remain a price taker in the negotiations. It would be up to the mainland to decide, which health code to use and when the border can reopen.