China has seized the global lead in tackling Big Tech lending which threatens to destabilise finance in multiple jurisdictions.

Over 11 days last month, China’s consumers set their 12th record for online shopping, buying 1.77 trillion yuan (US$270 billion) worth of merchandise, almost the size of South Africa’s annual economic output.

For the 800 million customers who shopped in November 2020 – like the alias Softwind who spent 5,000 yuan on clothes – credit was readily on tap, with big data and artificial intelligence helping to assess, approve and process loan applications in split seconds. Supported by a world-beating logistics network, the journey from e-shop to customer is so effortless that Alibaba Group Holding’s annual sale has been the planet’s largest online shopping bonanza, bigger than Black Friday and Cyber Monday combined, for several years.

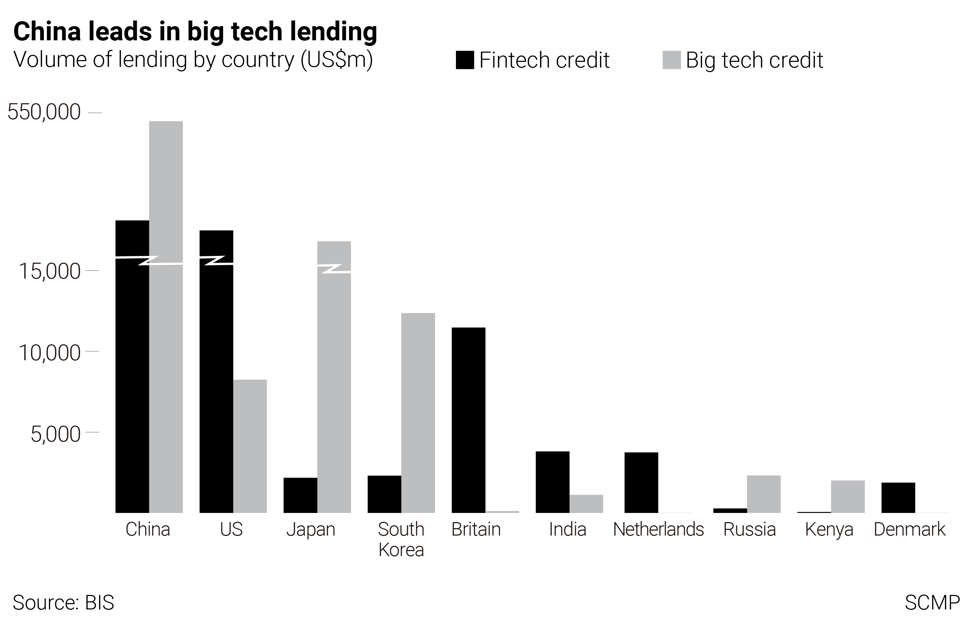

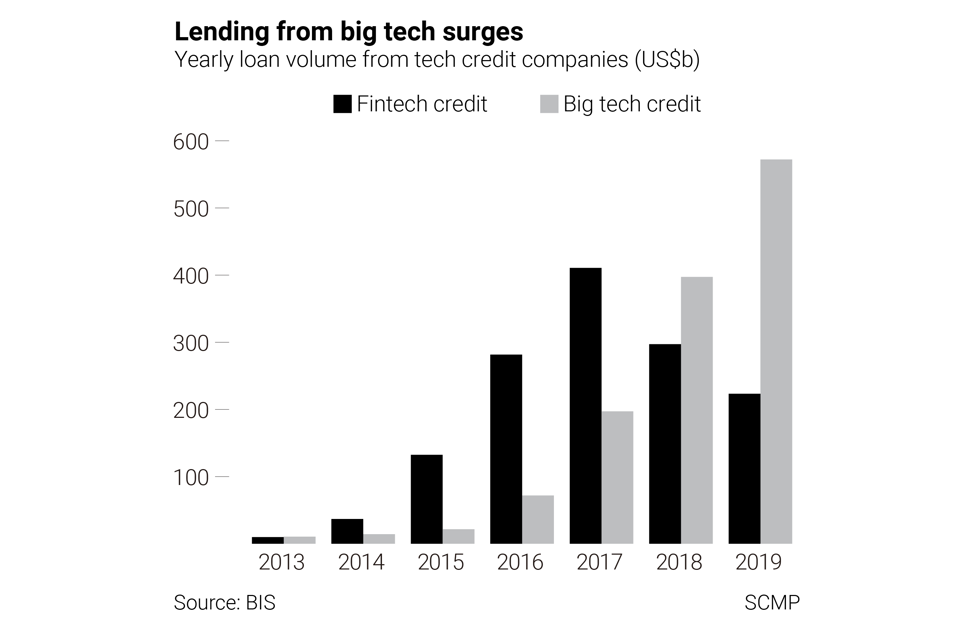

Technology-enabled financial services, or fintech, has grown exponentially in China in less than a decade, as the world’s largest population eagerly embraces every new smartphone application that promises convenience. The explosion in consumer credit – and how regulators rein in emerging risks – is a lesson for the rest of the world, especially for Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia and Africa where fintech credit is also growing fast.

“This huge, explosive innovation has gone far faster in a few years than what regulation and supervisory capacity can run,” said Agustin Carstens, general manager of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the Swiss-based monetary authority for global central banks, during a recent conference.

Online payment is the foundation of China’s fintech phenomenon, as customers leapfrogged credit cards and bank cheques straight to transactions via 900 million smartphones. By 2018, China’s fintech companies processed the equivalent of 38 per cent of China’s economic output in online payments.

There were 1 billion users on Alipay’s e-payment platform operated by Alibaba’s affiliate Ant Group in June, while WeChat Pay claimed 900 million users in February.

The payments generate scads of user data from addresses to shopping habits that let fintech firms create more accurate assessments of borrowers’ creditworthiness than banks, allowing them to lend without asking for collateral. Ant’s non-performing loans averaged 1.3 per cent, lower than the 2 per cent average among China’s state-owned banks in September.

That makes Big Tech and their fintech offshoots the “monopolies in information,” in the words of the BIS’ Carstens.

MYBank, an online commercial bank and Ant’s affiliate, offered 400 billion yuan of collateral-free credit to small businesses in October to help them prepare for Singles’ Day, China’s annual shopping bonanza in November. The offer was about 20 per cent of the corporate loans book at Postal Savings Bank of China, the lender with the widest network in the country, over an entire quarter.

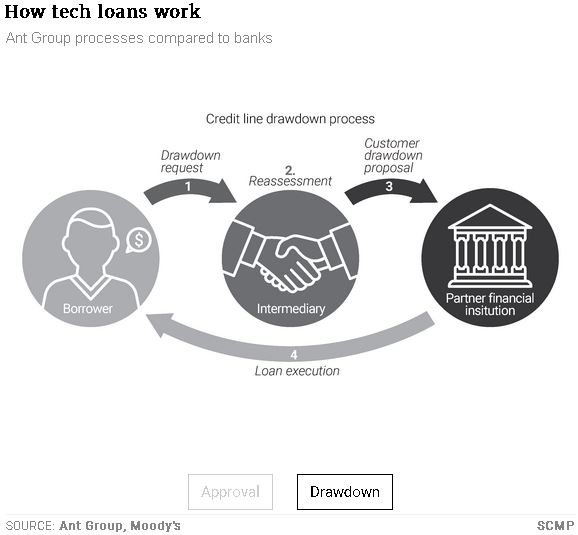

MYBank’s technology is so slick that loans take less than three minutes to apply for on a smartphone, less than one second to approve, all done without human intervention.

Regulators say the troves of data that feed Big Tech companies’ algorithms pose a threat to privacy.

“We have to think [about] and regulate the usage of consumers’ private information for commercial purposes. That is a big challenge that worries me,” said Yi Gang, governor of the People’s Bank of China at a fintech conference.

Fintech firms lent US$516 billion in 2019, 42 per cent higher than the US$363 billion in 2018, according to China’s central bank.

“Some already think they are too big to fail,” the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s chief executive Eddie Yue Wai-man said, referring to the common refrain during the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis when regulators were pilloried for bailing out banks on the brink of collapse.

To be sure, fintech companies promote financial inclusion by helping small borrowers that lack collaterals gain access to credit. China’s small businesses needed 89.7 trillion yuan of funding last year, 52 per cent of which was unmet by banks.

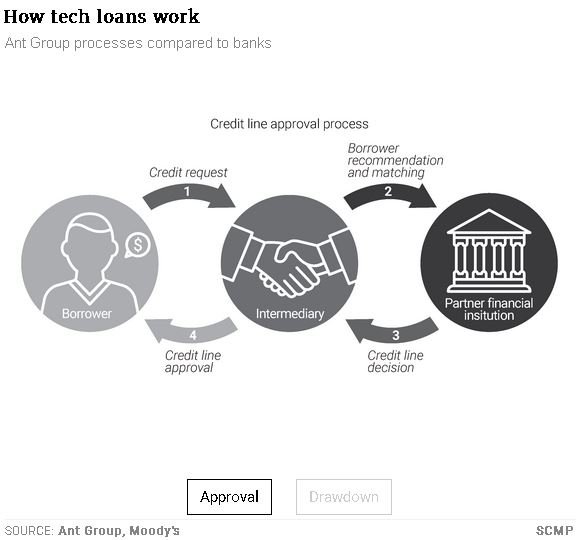

Loan applications gathered by fintech platform are assessed and offered to banks in packages, which then conduct their own due diligence and decide whether to lend or not. The relationship is raising concerns about banks’ dependence on digital platforms to find borrowers.

“At the systemic level, operational risks are increasing, such as the increased reliance on third-party information,” said Klaas Knot, vice chair of the Financial Stability Board and president of Dutch central bank De Nederlandsche Bank, citing a paper on the dangers of Big Tech credit.

China, the global leader in fintech, is again most at risk.

Ant matches borrowers with about 100 banks, lending 1.73 trillion yuan to consumers and 400 billion yuan to small businesses. The fintech firm puts up 2 per cent of this capital, the rest went onto the books of banks or was securitised. Regulators cleared Ant to sell US$3 billion worth of asset-backed securities last month.

JD Digits absorbed 4 per cent of loans by its credit units Jiantiao and Baitiao in June, while the rest is offloaded among 600 financial institutions. The two units lent 261.2 billion yuan in the first half, growing by 110 per cent every year on average over the past three years.

Shanghai-based fintech Lufax Holding, backed by China’s biggest insurer Ping An Insurance (Group), said its retail credit balance hit 535.8 billion yuan in September. It took on 2.8 per cent of the loans and passed the rest to over 50 financial institutions. Lufax said earlier this week it is raising its credit exposure.

Tencent’s services include microloan product Weilidai through its WeBank affiliate, which lent over 3.7 trillion yuan to more than 28 million customers in nearly 600 Chinese cities last year. WeBank declined to specify the number of banks it co-lends with.

Banks’ heavy reliance on fintech is relatively new and unseasoned algorithms could also introduce risk into loan portfolios, said regulators. Regulators also fear that banks will not have collateral to fall back on if something does not go wrong with data-driven lending.

Algorithms can potentially introduce bias, barring swathes of borrowers from credit. Machine-learning tools can yield combinations of borrower characteristics that predict race, religion or gender. An algorithm may rate an ethnic-minority borrower at a higher risk of default because similar borrowers have traditionally been given less favourable loan conditions.

Regulators are also fretting about cybersecurity as finance shifts online, from defence against hackers and malware to outages caused by a heavy drain on electricity.

“We cannot afford mistakes or accidents” in this field, said Carstens. “The core of networks should be public goods and extremely resilient.”

Regulators also fear some of China’s 7,227 microlenders might push high-interest rate loans onto those who can least afford them, such as students or farmers.

Illustrating the problem are the 20,000 members of Debtors’ Union chat group, each earning less than 6,000 yuan a month. Members borrow between 30,000 yuan to as much as 1 million yuan from credit cards and fintech apps, with the record holder owing 15 million yuan. Most have to rely on family and friends to bail them out.

A user with the alias F said she had run up 150,000 yuan of debt on Ant’s Huabei, Meituan’s Meituan Lend, Baidu’s Umoney and ride-hailing app Didi Chuxing Technology’s Didi Finance unit.

Loan recovery methods in China can be brutal, as they are often outsourced to unscrupulous debt collectors. More than 100 cases were reported in 2016, involving loan sharks forcing women college students to hand over naked selfies to ensure they would pay their loans.

Most fintech firms lend at cheaper rates than the banking industry. Credit-card rates are capped by the central bank at 18 per cent a year. Private loan interest rates above 36 per cent are deemed illegal.

Ant’s annual percentage rates (APRs) averaged 14.6 per cent, below the government’s 15.4 per cent cap for one-year private loans. Private loan interest rates above 36 per cent are deemed illegal. Lufax has lowered its APRs for new borrowers below 24 per cent. That said, other online lenders have charged higher rates.

Even though banks are partners with fintech firms, enough of them felt squeezed out for their grumbling to filter up to the bank regulator.

“Financial service providers have been excessively chasing profits, carrying out predatory lending, and using technology to mislead financial consumers” during the Covid-19 pandemic, said Guo Wuping at the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), who wrote that fintech’s credit services are akin to banks’ small loans, and should be regulated as such. “Regulatory arbitrage behaviour has occurred, and unfair competition with licensed financial institutions.”

On November 2 as Singles’ Day got under way, the CBIRC rolled out draft rules proposing to cap loans by the country’s 7,227 microlenders. The draft was released three days before Ant’s shares were due to start trading in Shanghai and Hong Kong and derailed the US$37 billion initial public offering. A clause in the proposed rules requires fintech firms to fund at least 30 per cent of their loans, aligning them with banks in the regulators’ eyes.

Eight days later on November 10, antitrust regulators followed with another set of draft rules to look into potential monopolistic behaviour by Big Tech platforms.

“Financial technology companies use oligopoly status to charge excessive fees and increase the cost of financial consumers,” said CBIRC’s Guo.

Fintech is under intense regulatory scrutiny, and China’s role as a trailblazer puts the country’s fintech pioneers like WechatPay and Ant in focus.

F has started to close accounts at Ant’s Huabei and other apps. “When I can get the credit from these online apps, I spend freely and often spend more than I earn. I have to stop, and the best way is to cut off the credit.”

China’s regulators agree and are closing the spigot of online credit.