‘If diners don’t use it, how could a restaurant waiter, or even operator, force them to do so?’ asks Hong Kong restaurateur Simon Wong.

Hong Kong business operators have expressed concerns over how they would enforce a new rule requiring customers to use the Covid-19 risk exposure app when they reopen after Lunar New Year.

At least two “substitutes” for the app were already found on online discussion forums on Thursday. Some Hongkongers have developed interfaces that look exactly like the one created by the government, so patrons can skip the recording procedures by screencapping and showing a fake page.

Authorities on Wednesday announced that restaurants could offer dine-in services till late into the night with four people per table from February 18.

An eatery displays a QR code for the Leave Home Safe Covid-19 risk-notification app.

An eatery displays a QR code for the Leave Home Safe Covid-19 risk-notification app.

Premises such as cinemas, massage parlours, gyms and theme parks could also reopen from that day if the coronavirus situation in the city remained stable.

But health authorities also forced at least 14 types of businesses to either require patrons to scan the “Leave Home Safe” app or leave their personal details as prerequisites for reopening.

Failure to comply with the rules could lead to a suspension of business for three to 14 days, on top of existing penalties. Restaurants would also lose the privilege to stay open later.

The app – which has been downloaded 55,000 times and covers some 70,000 public and private venues across the city – has so far been used by patrons voluntarily. When users of the app enter a venue, they have to scan a specific QR code displayed on the premises. When exiting the venue, they have to press “leave” on the app.

Francis Fong, president of the Hong Kong Information Technology

Federation, warns people that those using the fake interfaces may be

accused of the offence of accessing a computer with criminal or

dishonest intent.

Francis Fong, president of the Hong Kong Information Technology

Federation, warns people that those using the fake interfaces may be

accused of the offence of accessing a computer with criminal or

dishonest intent.

Allaying patrons’ privacy concerns, officials said the check-in data would be encrypted and stored only on the users’ mobile phones for 31 days, and would not be stored in any government or other systems. The app will only notify users if a person confirmed with Covid-19 had recently visited those places.

The government earlier said the app’s access rights to photo albums and USB storage on smartphones, and to users’ Wi-fi connections, had also been blocked.

But some Hongkongers still seem to be hesitant about using the app. On the popular LIHKG forum, young people have suggested various ways to cheat the government’s anti-pandemic surveillance mechanism.

Some forum users have created and shared web interfaces that look similar to the app. On such interfaces, people only need to input the name of the place they are visiting, and the app will show the venue owners or representatives a “fake record” similar to the one displayed on the government’s app.

A spokeswoman for the Food and Health Bureau said although the rule of scanning the code was not mandatory for customers, the government needed the cooperation and self-discipline of the public to combat the pandemic. If there was a rebound of cases, the government would have no choice but to significantly tighten social-distancing measures again, she said.

The Post has also contacted police for comments.

Francis Fong Po-kiu, honorary president of the Hong Kong Information Technology Federation, warned that people using the fake interfaces might be accused of the offence of accessing a computer with criminal or dishonest intent.

“It is also selfish to use a fake app to escape from being tracked,” he said. “The app so far has shown no clues in leaking out users’ private information. It has only warned authorities when there is a confirmed case at a venue. People should avoid going out if they are afraid, instead of creating fake records.”

But some business operators were concerned about how they would enforce the rule.

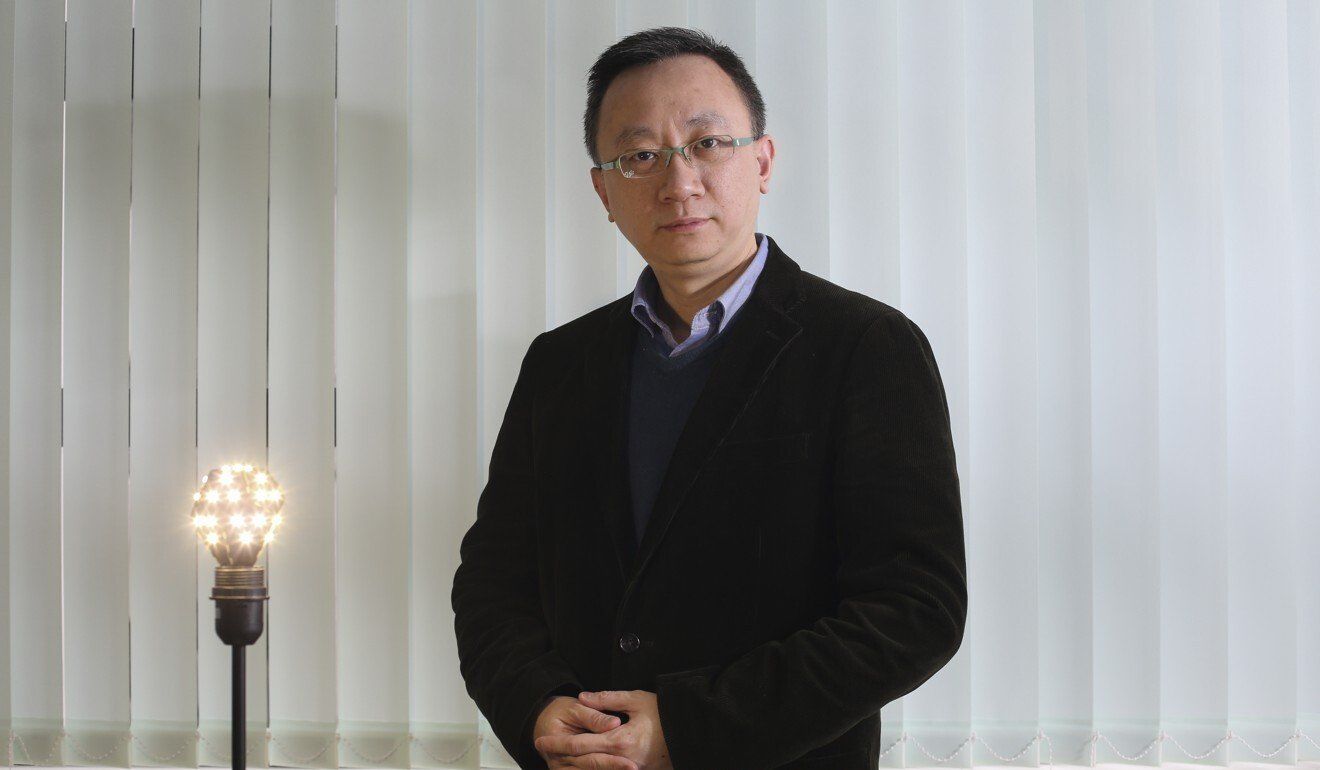

Restaurateur Simon Wong Kit-lung, who runs almost 40 eateries under the LH Group, said most of the establishments had put up the QR code since the app was launched some three months ago.

“The issue is with the diners. If they don’t use it, how could a restaurant waiter, or even operator, force them to do so? Can we seize their phones to check whether they had scanned the code before we allowed them in? The best we can do is to urge customers to scan the code.”

Simon Wong Ka-wo, president of the Hong Kong Federation of Restaurants and Related Trades, also said asking customers to use the QR code or leave contact details could result in disputes between diners and employees, adding it was unfair to ask eateries to shoulder the responsibility of ensuring people followed the rule.

Ray Or Chuen-ting, convenor of the Fitness and Combat Sports Alliance, said: “Very few customers were willing to use the app in the past. I doubt whether they would be willing to download the app simply because of doing exercise.”

Or said for his gym, he could easily record customers’ contact details during each visit given the information was already stored in his computerised system.

Elaine Lau, who owns a local San Choi noodle shop in Causeway Bay, also said it would be difficult to force the diners to scan the code.

“We would need extra manpower to check the diners, or even need staff to record their personal details outside the shop. It’s just creating a fuss,” she said. “Customers might simply not want to dine in.”

Lau said at present, fewer than one customer would use the app every day, and she was still considering whether they would run their businesses at night if the owners had to bear huge consequences.

But Chow Chun-yu, president of the HKSAR Licensed Massage Association, said the trade would have no problem with using the app.

“Our customers would understand it is for their good. They also have high trust in our operations. There should not be any privacy issue. Many of the massage parlours have already put up the QR code,” Chow said.

Restaurateur Simon Wong says many have put up the QR code since the app was launched some three months ago.

Restaurateur Simon Wong says many have put up the QR code since the app was launched some three months ago.

Secretary for Food and Health Professor Sophia Chan Siu-chee defended the app on Thursday, saying scanning QR codes was a simple way to help record where residents had been.

“I understand there are some concerns over the app, but even when you book tables at restaurants, you leave your personal details, and after you scan the code, the app does not display any of your information. I suggest people should give it a go,” she said, addressing concerns over potential privacy issues.

And not all customers are concerned.

One father, surnamed Chan, who has two kids aged 8 and 9, supported the proposed rule.

“It is more desirable,” he said. “I’ll be using it as well, or else why would the government need to create such an app [to trace the contacts]?”

Another father, also surnamed Chan, said he “would try to cooperate” with the government’s requirements when visiting those premises.

“There are infected cases across Hong Kong, so for sure there will be risks everywhere ... If the government requires, we will try our best to adhere to the rules, and use the app and the QR code when needed.”

Privacy concerns over Covid-19 contact-tracing apps have been raised by people in various other countries and regions.

In Singapore, anyone entering a public venue must scan a code on the “SafeEntry” app and register with a name, ID or passport number, and phone number.

If somebody tested positive for Covid-19, contact tracers would use the app to track down those who got close enough to be potentially infected.

There is also “TraceTogether”, an app that uses Bluetooth to ping close contacts. If two users are in proximity, their devices trade anonymised and encrypted user IDs that can be decrypted by the Ministry of Health should one person test positive for Covid-19.

It sparked controversy last month after the Ministry of Home Affairs said the data could also be accessed by police for criminal investigations.

In New Zealand, the “NZCOVIDTracer” allows users to scan official QR codes to create a private digital diary of places he visits. The app also uses Bluetooth tracing to keep a record of the people one has come close to, so contact tracers can get in touch if needed.

Authorities in New Zealand have allayed people’s privacy concerns by making the app “decentralised”, leaving location data – which is loaded via QR codes – and interaction information, fed via Bluetooth tracing, on people’s phones until it is needed for contact tracing.

The country’s privacy watchdog has proposed legal amendments to ensure the government will not use the data for surveillance or criminal investigations.