The resurgence of the virus in northern England poses political problems for Boris Johnson

On August 14, Boris Johnson sparked panic on the beaches when he decided to add France to England’s quarantine list. Thousands of Brits dashed home from a country recording 30 Covid-19 cases per 100,000, hoping to avoid two weeks of self-isolation at the end of their vacation.

While danger lurked abroad — British tourists were told to venture to foreign climes “with their eyes open” — Mr Johnson was confident the situation at home was under control. Workers were urged to return to their offices; the taxpayer subsidised cheap meals under an “eat out to help out” scheme.

The new Covid-19 test and tracing system — on which the government had spent more than it spends on nursery and university education at 0.6 per cent of national income — would allow the country to get back to work and enjoy life, while suppressing the virus until a vaccine was available.

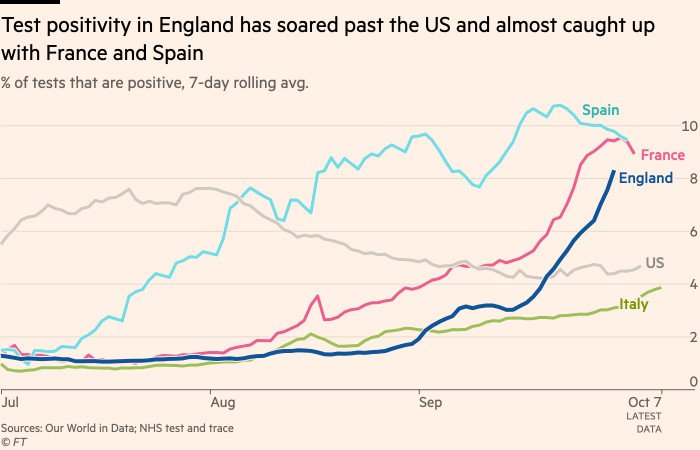

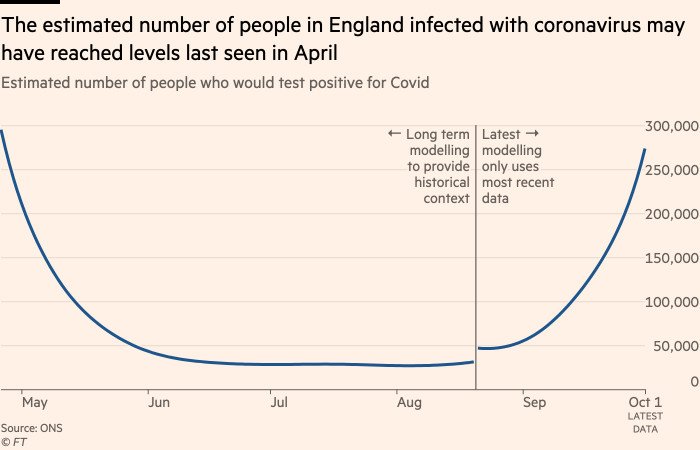

Since then, a second wave of coronavirus has engulfed the UK at a pace not seen in other large European countries. Mr Johnson’s “world-beating” test and trace system struggles to cope on good days; on bad days it is a farce.

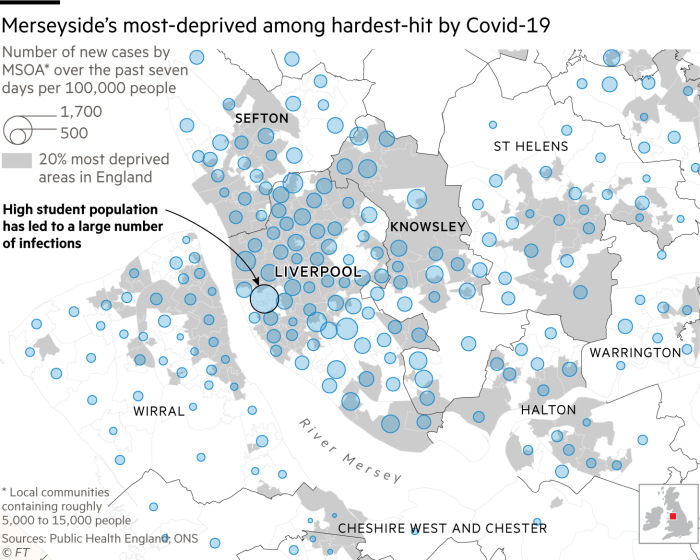

Cities in the north of England have been particularly badly hit, with rates above 500 per 100,000 in Manchester, Liverpool and Newcastle — at least 15 times higher than the rate in France on that chaotic day in August.

From having a rate of infection per 100,000 people of 11.4 in the week up to August 15, well below the EU average of 20.5 and the US rate of 110.7, the UK’s positive case rate has now exceeded both the EU and US totals. It stands at 133.7, higher than the US rate of 96.9 and the EU rate of 77.2.

Mr Johnson used to say he would contain a second wave of Covid-19 with a localised “whack a mole” strategy. In the north of England, the moles are winning. While cases of coronavirus remain subdued in London and the south-east, in deprived northern towns and cities they are popping up fast.

“The virus has spread right across the community. We are seeing lots among the older population. I wish we could pinpoint how it is spreading. We don’t know. We need a total lockdown,” said Sean Donnelly, deputy leader of Knowsley council, the authority next to Liverpool that now has the second highest rate of infection in the country.

“Track and trace has failed. We are getting passed cases seven days after they tested positive. That is too late,” he said. In the week to October 8, there were 907 new cases, and a rate of 601.2 per 100,000 population, up from 365.2 a week before.

In many northern cities the infection rate has jumped as students have arrived at universities, which have big central campuses and tightly packed halls of residence. In other former cotton towns such as Blackburn and Burnley, the virus has taken hold among families of south Asian heritage who often live in smaller houses with three generations under one roof.

But the situation is far from straightforward. Knowsley has no student accommodation, and its population of 145,000 is 97 per cent white, living in homes with gardens and wide streets and play areas.

Christine Mimnagh, a local GP, has many answers including a legacy of factory work and high unemployment: “You have a population that already suffers poor health. Respiratory disease is high. Car ownership is low. People have to use public transport. They do jobs that you cannot do from home — care work, bar work.”

Many are on zero hour contracts, so if they self-isolate because of a positive test, they do not get paid. “Diseases flourish where the environment suits them,” Dr Mimnagh said.

The message is that while the first wave travelled by aircraft and railcar to big global cities with mobile populations, the second has taken the bus and seized the poor and poorly. Older, more unhealthy, these places are less equipped to fight it off.

The virus gripped London first and peaked in the north a few weeks later. So when lockdown measures were eased from May, there was still a higher caseload. “We took the brakes off too early,” said Dr Mimnagh.

Locals have suggestions of their own. On October 1 the government made it illegal in many northern areas for two households to mix indoors including in pubs and restaurants. Amanda Costa, a nurse out shopping in the town of Kirkby, said: “People do not adhere to the rules. I have seen videos of people in the city centre dancing all packed together.

“The young think they are invincible. But I’ve seen younger people in the hospital.”

24-year-old Christopher Walsh, who lost his job in the first lockdown in March and remains unemployed, blamed teenagers gathering in parks and on street corners. “Then they take coronavirus home to their parents. They should shut the parks at 6pm,” he said.

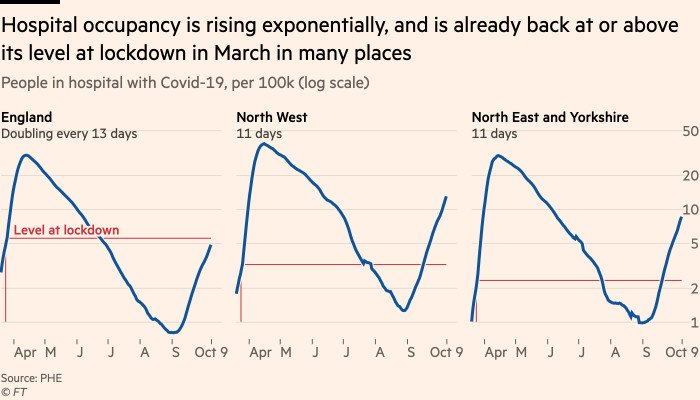

Liverpool’s hospitals are filling. The Liverpool University Hospital’s NHS Foundation Trust is treating 200 Covid-19 patients, already half the level of the April peak and rising.

Mr Johnson’s allies despair at the state of the test and trace system, which lost almost 16,000 cases this month because they exceeded the maximum file size that could be loaded into a central system. Infected people then unknowingly spread the disease.

Dozens of MPs in Mr Johnson’s Conservative party are opposing new restrictions. They argue that existing rules to stop social mixing are not working and there is little evidence to support new lockdowns. Some argue that the vulnerable should be shielded, while the rest of the country should be allowed to get on with life.

Graham Brady, who represents rank-and-file Tory MPs, said this week: “These rules are a massive intrusion into the liberty and private lives of the whole British people, and they’re having a devastating economic effect as well.”

The data suggests the surge in cases is spreading. In England, testing statistics are collected in very localised areas comprising only 7,200 people each. In mid-August, just 10 per cent of these areas reported more than two cases in a single week, a figure that rose to 57 per cent in the last week of September and jumped in the week ending October 4 to 77 per cent.

Increasingly severe restrictions are now being imposed across the country with disastrous effects for the economy, saddled for the first time with debt above £2 trillion, and output is still 9.2 per cent below its pre-pandemic level. Pubs and restaurants are to be closed across much of Scotland and northern England. Government’s scientists are warning that even these measures will not be enough.

The return of the pandemic poses serious political problems for Mr Johnson. On April 13 a YouGov survey found that 66 per cent of people thought the prime minister was doing well; now it is just 35 per cent.

Mr Johnson won the December 2019 election thanks in considerable part to the support of former Labour voters in the midlands and north of England, the very regions now suffering most from coronavirus.

Andy Burnham, Labour mayor of Greater Manchester, has accused the prime minister of treating the region with “contempt”, of failing to consult local leaders and applying lockdown measures in the north more readily than in London and the south.

It is a toxic narrative for Mr Johnson, who this week urged his “virtual” party conference to look beyond the crisis, presenting a vision of a “New Jerusalem” of offshore wind farms, gleaming new hospitals and “Brexit blue” passports. But each day the grim statistics of Covid-19 draw him back to the present.

In his conference speech he sounded less confident that the “vaccine cavalry”, as described by health secretary Matt Hancock, will actually arrive next spring; Mr Johnson used the telling phrase “if and when we get one”.

For now, as Chris Whitty, the government’s chief medical adviser, put it, Britain is heading into “a long winter”.