Liaison office publicised about 20 trips by director Luo Huining and his deputies, as they visited homes, youth clubs, a building site and fishermen.

Senior officials from Beijing’s liaison office in Hong Kong emerged from their heavily guarded headquarters in Western district earlier this month and popped up in multiple unexpected locations across the city.

The office publicised about 20 such trips by director Luo Huining and his deputies, as they went to various places including a construction site, a fishing village in Lantau, Chinese medicine halls, youth clubs and even fishing boats moored in Aberdeen.

After the first day, on the eve of the country’s National Day, the office made plain the mission.

“The liaison office doesn’t only value the opinion of representatives of various sectors in society. It also values directly listening to grass-roots residents’ voices,” it said in a statement, signalling this new approach to “listen directly” to the ground would augment their traditional outreach.

At a media briefing on Monday, deputy director Lu Xinning revealed the scale

of the outreach was much bigger – with far wider implications on the city’s governance than analysts had expected when the drive began.

Luo Huining (centre) chats with fishermen in Aberdeen.

Luo Huining (centre) chats with fishermen in Aberdeen.

In all, hundreds of liaison office employees were mobilised to visit 979 housing units – subdivided flats, and public, subsidised and transitional homes – and small businesses. They met 3,985 residents and received 6,347 pieces of feedback, from livelihood concerns to challenges of working in mainland China.

Based on these inputs, a source said the office had compiled a to-do list of more than 500 measures to be implemented. Lu said it would pass on to the Hong Kong government items that fell under the latter’s purview, while pledging to immediately tackle those that came under its scope, including such mainland-related issues as the border reopening or the work of authorities there.

Lu also said there would be more such outreach programmes, adding they would be “normalised”.

Lu Xinning visits residents in a subdivided flat in To Kwa Wan.

Lu Xinning visits residents in a subdivided flat in To Kwa Wan.

That piece of news along with the more than week-long high-profile drive has raised eyebrows, as political watchers asked if the liaison office was complementing or competing with the local government in wanting to serve residents.

The tours have also reignited talk of whether the office was becoming a “second governing team” a term ironically coined by one of its own officials over a decade ago.

Both sides, however, were quick to tamp down such speculation. Asked at the media briefing if the liaison office was crossing the line of “one country, two systems”, Lu replied that among its list of major duties was to “liaise with various sectors in Hong Kong society, foster Hong Kong and mainland exchanges, and reflect Hong Kong residents’ opinion about the mainland”. In a nutshell, they were just doing their job.

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor also shrugged off concerns over a second governing team, saying she “could not see or hear such inclination”.

Asked again on Tuesday, Lam was profuse in her thanks to the liaison office for its outreach efforts but also said her “gut feeling is that those views and ideas and suggestions should be very close to what we already know.” She cited such issues as housing, youth mobility, wealth disparity and the cost of housing.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

The answers, however, were unlikely to snuff out talk, analysts said, especially if the visits became more frequent and no clarity on where the lines of responsibility and accountability lay. The liaison office’s actual motivations for these visits, the message it was sending, and to whom, had yet to be fully understood by the public, they said.

Was the liaison office trying to set an example for or offer a critique to the government? But could its actions also cause confusion and raise expectations among residents? These were also among the questions analysts have raised.

The timing of the tours also piqued many observers’ curiosity, beginning just days before Carrie Lam was due to deliver her annual policy address

on October 6.

Hong Kong’s northern New Territories.

Hong Kong’s northern New Territories.

Housing, housing, housing

From pictures released throughout the previous week, there appeared to be a common theme to the “listening directly” drive: the officials were not rubbing shoulders with the city’s elite, but getting to know ordinary, hardworking, salt-of-the-earth types often in their well-worn work clothes.

And they did not just pop into workplaces. They went into many homes, especially those of the poor and down-and-out.

On the first day, Luo met residents in Mong Kok living in “cage homes”, possibly the worst and smallest form of housing in the city, no larger than the size of a single bed. The office quoted Luo as saying his “heart sank” after he saw such living conditions.

In a separate statement, the office reported that deputy director Chen Dong, who visited several villages in the northern New Territories on September 30, said he would support the city’s government in development planning in the area. Chen also encouraged stakeholders to make recommendations.

By coincidence or in concert, Lam during her policy address unveiled plans for a new Northern Metropolis near the border with Shenzhen with an innovation and tech corridor as its engine and providing housing for 2.5 million people.

Chen Dong visits a farm in Tin Shui Wai.

Chen Dong visits a farm in Tin Shui Wai.

That a central focus of the liaison office’s visits was the city’s housing situation was to be expected given how Beijing has been urging the local government to address “deep-rooted issues” in society.

In the midst of the 2019 protests, Vice-Premier Han Zheng signalled to Lam that Beijing wanted her to do more to tackle the housing issue, as he called for measures that were “more proactive and more effective in solving livelihood issues … especially the housing problems facing middle- and lower-income families …”

Beijing seemed to believe the 2019 social unrest sparked by a withdrawn extradition bill was also because of the city’s lack of affordable housing and youth mobility.

In July, Xia Baolong, director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, also put the issue of housing front and centre when he set a target of ending subdivided flats and cage homes in the city by 2049.

The liaison office visits were part of this larger mission to put housing top of the agenda, Tian Feilong, an associate professor at Beihang University’s law school in Beijing, said. It also underlined how beyond Hong Kong’s political stability and economic development, the central government cared about the city’s social issues and the less well-off, he added.

“These visits will help the Beijing and Hong Kong governments to come up with targeted policies, and thus allow Hong Kong residents to have more confidence and trust in the city’s administration as well.”

Who is in charge?

While the liaison office’s more prominent role now might be welcomed by some residents, this was not always the case. In the past, the mere public appearance of a liaison office representative would spark outrage and warnings of a weakening of the city’s high degree of autonomy.

Fast forward to today, with the opposition in tatters and key figures in jail, the issue triggered a muted response, yet another sign of Beijing’s tightening grip on the city, analysts noted.

But the signs of these shifting sands of Beijing’s assertiveness had come much earlier, a political scientist, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said.

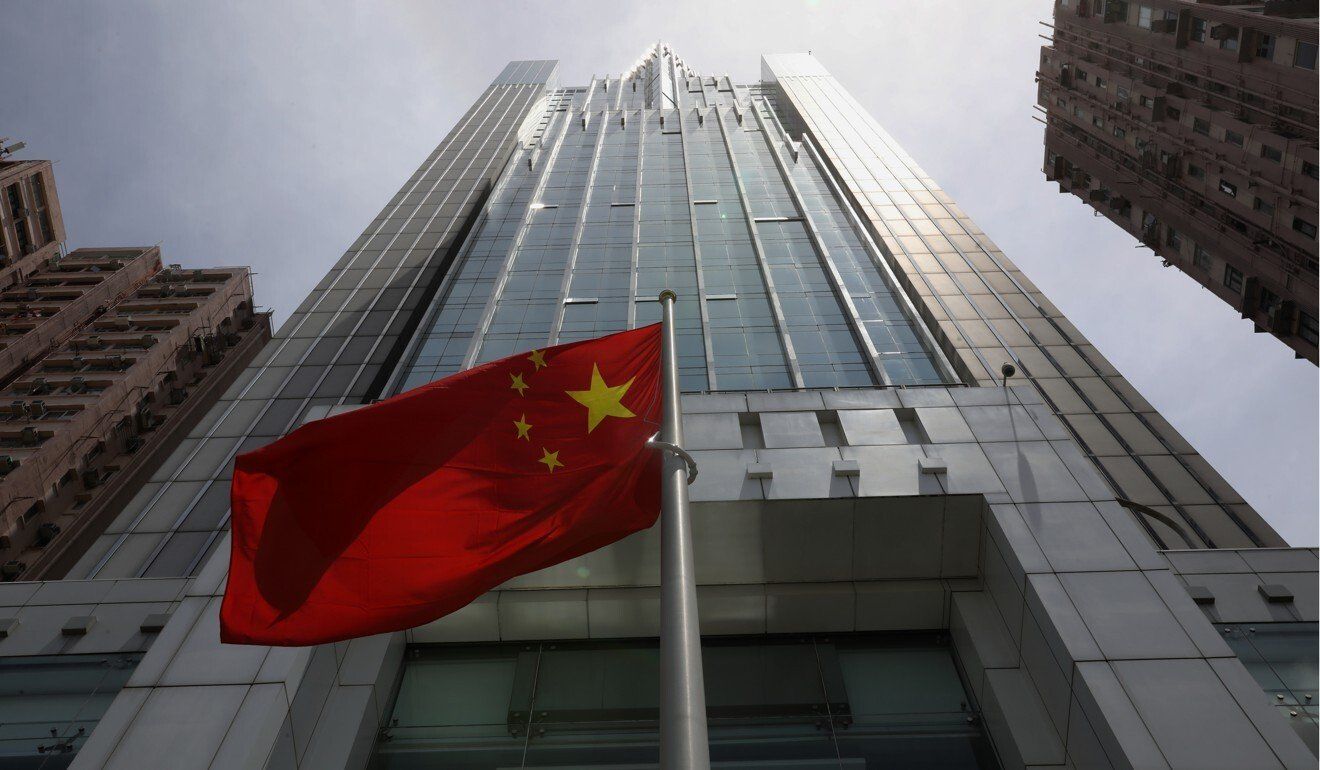

The central government’s liaison office in Hong Kong.

The central government’s liaison office in Hong Kong.

The professor believed that since Beijing made it clear in a 2014 white paper that the central government enjoyed “comprehensive jurisdiction” over the city, mainland officials overseeing Hong Kong affairs felt the need to be more visible and active.

“The liaison office felt the need to do more when their Hong Kong counterparts were not doing enough,” the analyst said.

Professor Song Sio-chong, of Shenzhen University’s Centre for Basic Laws of Hong Kong and Macau, dismissed concerns that the central government was ignoring the one country, two systems principle if the liaison office did more frontline work.

While it had exercised restraint in the past, the “black violence” of the 2019 protests changed Beijing’s thinking fundamentally, he said.

Song argued that Beijing’s understanding of its “comprehensive jurisdiction” over Hong Kong meant it could be involved in policies to ensure the city was on the right track, including how it exercised its autonomy.

Tian too pointed to the 2019 violence as ending Beijing’s “passive governance” of the city. “The consequence of its past permissiveness of ‘high degree of autonomy’ was that the loopholes in national security and risks of a ‘colour revolution’ got bigger and bigger. The Hong Kong government also faced various restrictions in doing its work,” he argued, citing the opposition’s filibustering as an example.

Tam Yiu-chung.

Tam Yiu-chung.

Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole delegate to the nation’s top legislative body, said residents had to accept Beijing had the last say on the city. “Our chief executive and some other principal officials were appointed by Beijing, so why see Beijing’s role negatively as interference?” he asked.

But a government source expressed concern that residents could get mixed signals as to whom they should be turning to for leadership and whom to hold accountable.

“It goes without question mainland officials can show their concern about Hong Kong’s issues, but if this is being done regularly, people might be confused and wonder whether they should complain to the city’s government or the central government about Hong Kong’s problems,” the source said.

There was also the risk that the city government’s actions could be seen as lacking in originality or just second-guessing the liaison office, said a source with knowledge of Lam’s drafting of the policy address.

Tian said there was no doubt that the liaison office visits – and the feedback they would yield – would pile on the pressure on local officials to perform. “It would be good if they feel the pressure.”

Connected to grass roots but dangers lurk

But others pointed out that the liaison office’s work was not just to let Lam or the administration feel the heat. Rather it was to signal to them that to succeed, they had to do more to connect with the ground and be a “responsive government”.

New People’s Party chairwoman Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, who advises Lam in her de facto cabinet, the Executive Council, said in a Facebook post on National Day that Luo’s visit showed that more senior officials needed to wake up.

“In comparison, Hong Kong officials … seem to be unmoved by various livelihood problems, so I just want to ask, ‘Officials, have you woken up yet?’”

Echoing Ip, the Democratic Party’s housing policy spokesman, Winfield Chong, said: “It should be the Hong Kong bureau chiefs solving the problems. It was pathetic that they needed the mainland officials to remind them like that, the ministers should be ashamed of themselves.”

Ip, a former security minister, said she believed that beyond putting the local government on notice, the outreach drive also underscored Beijing’s confidence in its governing system where legitimacy was not via the ballot box but through responsive governance.

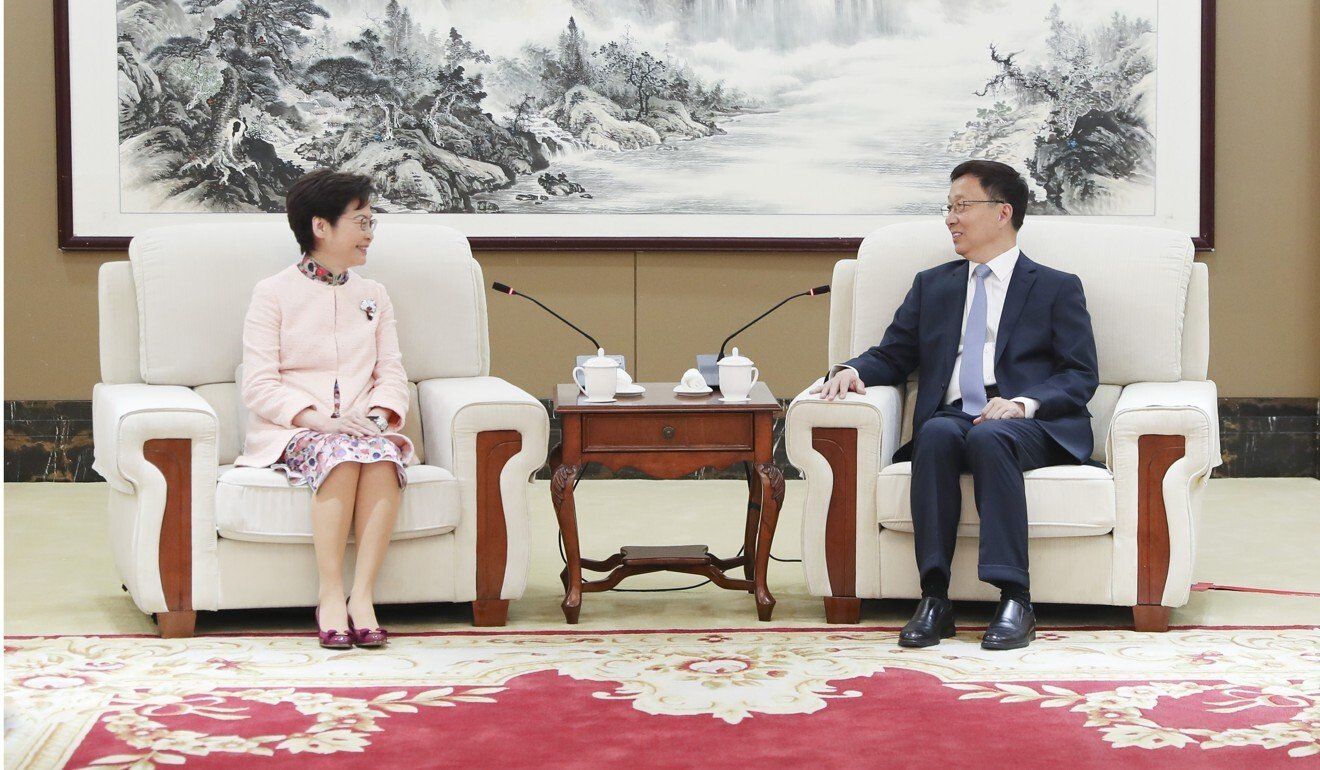

Vice-Premier Han Zheng with Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam.

Vice-Premier Han Zheng with Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam.

Beijing officials also hinted at the concept of responsive government. In its statement on Lam’s policy address, the liaison office stated plainly it hoped the authorities would “make better responses to the concerns of all sectors of society”.

Lam had gushed about the liaison office’s visits, saying these would help improve policymaking but brushed off suggestions it was becoming the city’s “second governing team”.

The description actually came from a liaison office head of research, Cao Erbao, who argued in 2009 that a team of mainland cadres had formed a “second governing team” in the city after the handover, a claim subsequently dismissed by other Beijing loyalists.

Such tropes had a way of becoming reality though, Chinese University political scientist Ivan Choy Chi-keung warned.

While the outreach drive could force Hong Kong officials to be more proactive in solving the city’s problems, it could also turn them into a passive, second-guessing administration, prone to waiting for directives from Beijing.

Choy also warned Beijing was taking risks with more direct involvement, especially if promises were not delivered by the local government.

“In the past, the liaison office was like an arbitrator or referee in Hong Kong’s social problems … now, no longer … residents could also divert their societal discontent from the city’s government to the liaison office, like they did during the protests.”