The ‘Light Hours’ exhibition examines connections between Canada and Hong Kong amid ‘Beijing’s tightening grip’, according to organiser Ho Tam.

When Canadian artist and publisher Ho Tam decided to put on a show devoted to Hong Kong identity at such a critical time in the city’s history, he found himself walking a fine line as he approached others to take part.

The Light Hours exhibition at his Eastside Vancouver gallery space would examine ties between Canada and the city he left as a child. But the political context was clear.

“As the light hours quickly pass before darkness falls on the once liberal and prosperous Hong Kong, now is the time for us to speak out like never before,” he writes in exhibition notes, referring to social unrest and political uncertainty amid “Beijing’s tightening grip”.

That theme saw some decline to take part. Tam, 58, has lived in Canada for more than 40 years, and has not visited Hong Kong since 2013, but other artists who spent more time in Hong Kong had more at stake.

Hong Kong-born artist and publisher Ho Tam is seen in his Hotam Press

Gallery, which is preparing to stage the Light Hours exhibition.

Hong Kong-born artist and publisher Ho Tam is seen in his Hotam Press

Gallery, which is preparing to stage the Light Hours exhibition.

“They have a more Hong Kong context, and they might have been afraid that being in this exhibition could jeopardise their fate or their relatives in Hong Kong … some don’t even want to touch the topic [of Hong Kong identity],” he said.

On the other hand, some artists turned down his approach when Tam told them he did not want the exhibition to be a “protest show”.

“I don’t encourage angry work,” said Tam. “I think that could be dangerous to the other artists participating too.”

In the end, 10 Hong Kong Canadian artists (in addition to Tam) agreed to take part in the exhibition, which will run at the Hotam Press Gallery from Saturday until August 29.

The show “seeks to open up a discourse about the complexity and possibility of a Hong Kong Canadian identity”.

Tam said the artists’ perspectives were diverse. Some are long-term immigrants, like Tam, but he said he was struck by how younger artists born in Canada were now clearly identifying as Hongkongers and exploring their roots there.

“For a long time everyone categorised [themselves] as Chinese Canadians. The Hongkongness didn’t really come out from that so much,” said Tam. “I’m hoping the exhibition will try to make us aware – is there such a thing as a Hong Kong Canadian, Hongkongness in Vancouver?

“The wave of immigrants from the 70s, 80s, 90s, now have their kids, and it is that generation that is carrying on this identity … I wasn’t thinking along those lines and suddenly I’m seeing this phenomenon,” he said.

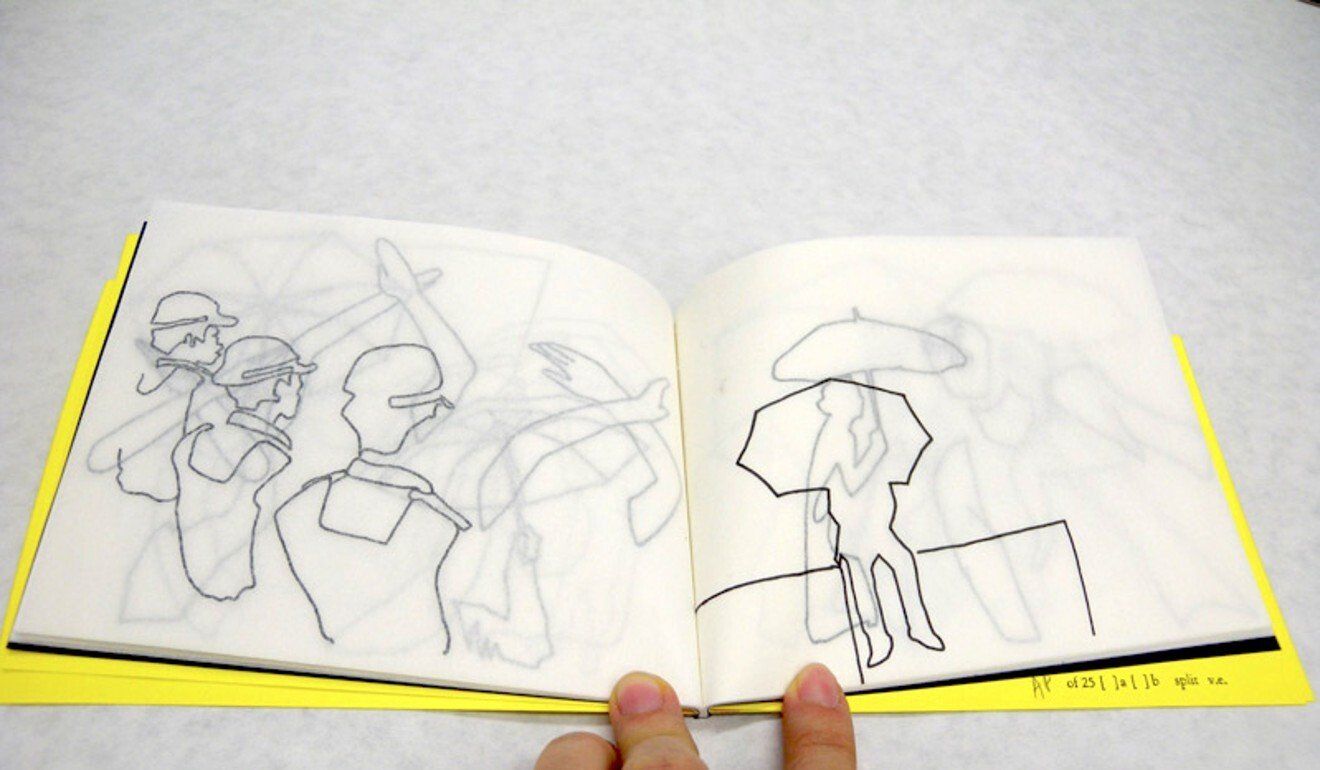

Artist Hei Lam Ng's “Umbrella” (2015) is a booklet of drawings from Hong Kong's 2014 protest movement.

Artist Hei Lam Ng's “Umbrella” (2015) is a booklet of drawings from Hong Kong's 2014 protest movement.

The artworks are likewise diverse, including Henry Tsang’s April 14 – 19, 1899 (2021), a silver gelatin print of armed Chinese soldiers originally taken around the time of the Boxer Rebellion; Dennis Ha’s Shirt (2021, work in progress), a uniform covered in the logos of Hongkongers’ businesses in Vancouver; and Kai Chan’s Red Star (2015), a sculpture of dangling jade.

Tam’s contribution consists of photography from Lessons (2000), originally a video-photo series he captured at his Hong Kong elementary school in 1998, in the wake of the city’s return to Chinese sovereignty.

Tam worked in advertising and as a community worker before settling on fine arts. His Hotam Press is an independent publisher of art magazines; its first project was The Yellow Pages in 1993, which focused on the Asian experience in North America.

His focus has long been on diaspora identity, while other projects have included sharing the work of mainland Chinese photographers.

“Because of my community-work background, I’ve always been interested in allowing other voices to be heard,” said Tam.

But since the “umbrella movement” protests in 2014, Tam has been more “tuned in” to political events in Hong Kong.

Artist Dennis Ha's “Shirt” (2021 work in progress) features the logos of

Vancouver businesses connected to the Hong Kong diaspora.

Artist Dennis Ha's “Shirt” (2021 work in progress) features the logos of

Vancouver businesses connected to the Hong Kong diaspora.

Tam’s imperative to address Hong Kong identity emerged in the wake of the National Security Law, introduced last year, and the suppression of the 2019 Hong Kong protest movement.

Yet at the same time he is ambivalent about “purely protest art”, a position that he agreed sounds like a contradiction. “I’m not interested in just talking to the converted,” he explained. “I want to open the show to many voices, and not everyone is on the same page as me.”

The genesis of the exhibition may have been Hong Kong’s political turmoil, but by focusing on Hong Kong-Canadian identity, Tam hopes to “make things more open to the community”.

“The exhibition is asking this question, does everything [about Hong Kong] have to be political? How is politics embedded in each of us?” he said.