Indonesia is the world's biggest tin exporter. But the land supply is almost gone, so miners are now risking their lives to extract it underwater.

Indonesia is the world's biggest exporter of tin, and more than 90% of the country's supply comes from the islands of Bangka and Belitung. But the deposits on land are almost gone, so unlicensed miners risk their lives to search for the precious metal on the seafloor.

Makeshift pontoons gather in the Indonesia Sea to form an illegal tin mine.

Makeshift pontoons gather in the Indonesia Sea to form an illegal tin mine.

Small crews spend long hours on these makeshift pontoons sifting through sand to find tin, which is used in phones, food cans, cosmetics, paints, and fuel.

Makeshift pontoons for an illegal tin mine in the Indonesian sea.

Makeshift pontoons for an illegal tin mine in the Indonesian sea.

Joko Tingkir, a tin miner, dives 65 feet underwater three or four times a day. An injury caused by diving makes him walk with a limp.

Joko Tingkir walks from the beach to his mining pontoon to start his work day.

Joko Tingkir walks from the beach to his mining pontoon to start his work day.

He spends hours searching the ocean floor for tin so he can feed his four children. He used to be a fisherman, but he left the trade because tin mining pays better.

Ibnu Hadi Rachmat

Ibnu Hadi Rachmat

The only safety equipment Joko uses is a diving suit and a scuba mask.

Joko stands onboard his mining pontoon in his diving gear.

Joko stands onboard his mining pontoon in his diving gear.

He breathes through a narrow oxygen tube, which is connected to an air compressor aboard the pontoon.

A crew member holds Joko's breathing tube.

A crew member holds Joko's breathing tube.

The tube can easily become tangled or break.

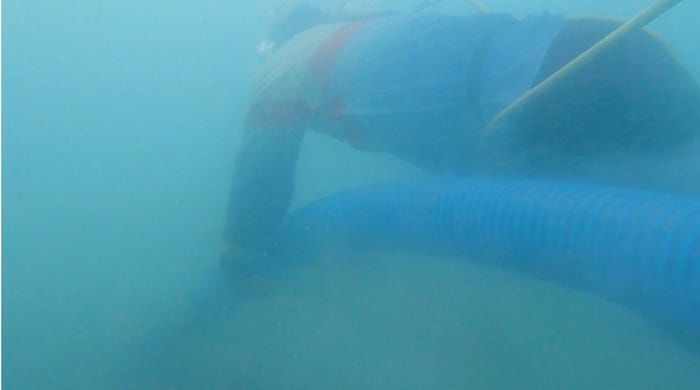

Joko's breathing tube and the mining operation's vacuum tube.

Joko's breathing tube and the mining operation's vacuum tube.

The air compressor can also leak toxic gases into Joko's air supply if it isn't filtered properly, leading to nitrogen poisoning, which could put Joko in a coma.

The air compressor that feeds Joko's air supply.

The air compressor that feeds Joko's air supply.

The compressor shut off once while Joko was underwater. He had to resurface quickly — a move that in some cases can trigger decompression, causing a diver's legs and arms to go numb.

When he reaches the seabed, Joko plants the blue suction tube firmly into the sand. He vacuums up a mixture of sand and water.

Joko holds the vacuum tube firmly in place at the seabed.

Joko holds the vacuum tube firmly in place at the seabed.

The crew aboard the pontoon checks it to make sure there's tin mixed in.

A crew member on board the ship holds a handful of tin.

A crew member on board the ship holds a handful of tin.

When they find tin, they briefly cut off Joko's air supply by bending his oxygen tube, signaling that he should hold the vacuum in place.

He stays underwater holding the vacuum for up to four hours a dive.

Joko blows bubbles from his scuba mask as he holds the vacuum tube in place.

Joko blows bubbles from his scuba mask as he holds the vacuum tube in place.

Workers mine all day and all night if they find a spot with a lot of tin. They say they can't risk leaving any behind.

A worker sorts through tin on the mining pontoon.

A worker sorts through tin on the mining pontoon.

The crew gets ready to collect the tin by laying down mats on the boat.

A crew member lays down mats on the boat to collect the tin Joko sucks up.

A crew member lays down mats on the boat to collect the tin Joko sucks up.

They run the water and sand Joko sucks up over the mats.

Tin is heavier than sand, so it sinks into the holes of the mat.

Tin collects in these mats while the water and sand run off it.

Tin collects in these mats while the water and sand run off it.

The leftover sand and water flow over the mats and back into the sea.

A mixture of water and sand gets returned to the sea.

A mixture of water and sand gets returned to the sea.

Next, crew members wash out the captured tin from the mats in basins on the side of the boat.

They drain the water from the basin and scoop the tin into bowls.

At the end of the day, the miners divide the tin among themselves so they can sell it individually. Joko takes the most, because his job is the riskiest.

Joko mines illegally because he can't afford a mining license. It's hard for unlicensed miners to find buyers, because the tin they mine is illegal.

Buyers that take the risk say they usually pay unlicensed miners 10% below tin's standard market price. Joko earns just $13 a day for his share.

The buyer for Joko's tin counts his money.

The buyer for Joko's tin counts his money.

PT Timah, a company owned by the Indonesian government, controls over a million acres of tin-mining territory in Bangka and Belitung.

The company has already extracted most of the tin on Bangka and Belitung, leaving behind massive craters of exposed rock that contain sulfide minerals. The sulfides react with the air and water, creating brightly colored toxic lakes.

The toxic acids that make these lakes so blue are contaminating waterways all over Bangka and Belitung.

Ibnu Hadi Rachmat

Ibnu Hadi Rachmat

PT Timah estimates about 16,000 tons of tin remain in its over 1 million acres of land reserves. But company data show 265,000 tons of tin can be found underwater around the islands.

Ibnu Hadi Rachmat

Ibnu Hadi Rachmat

Joko says he'll keep diving as long as there's tin left.

Joko carries his materials to the beach to start his workday.

Joko carries his materials to the beach to start his workday.