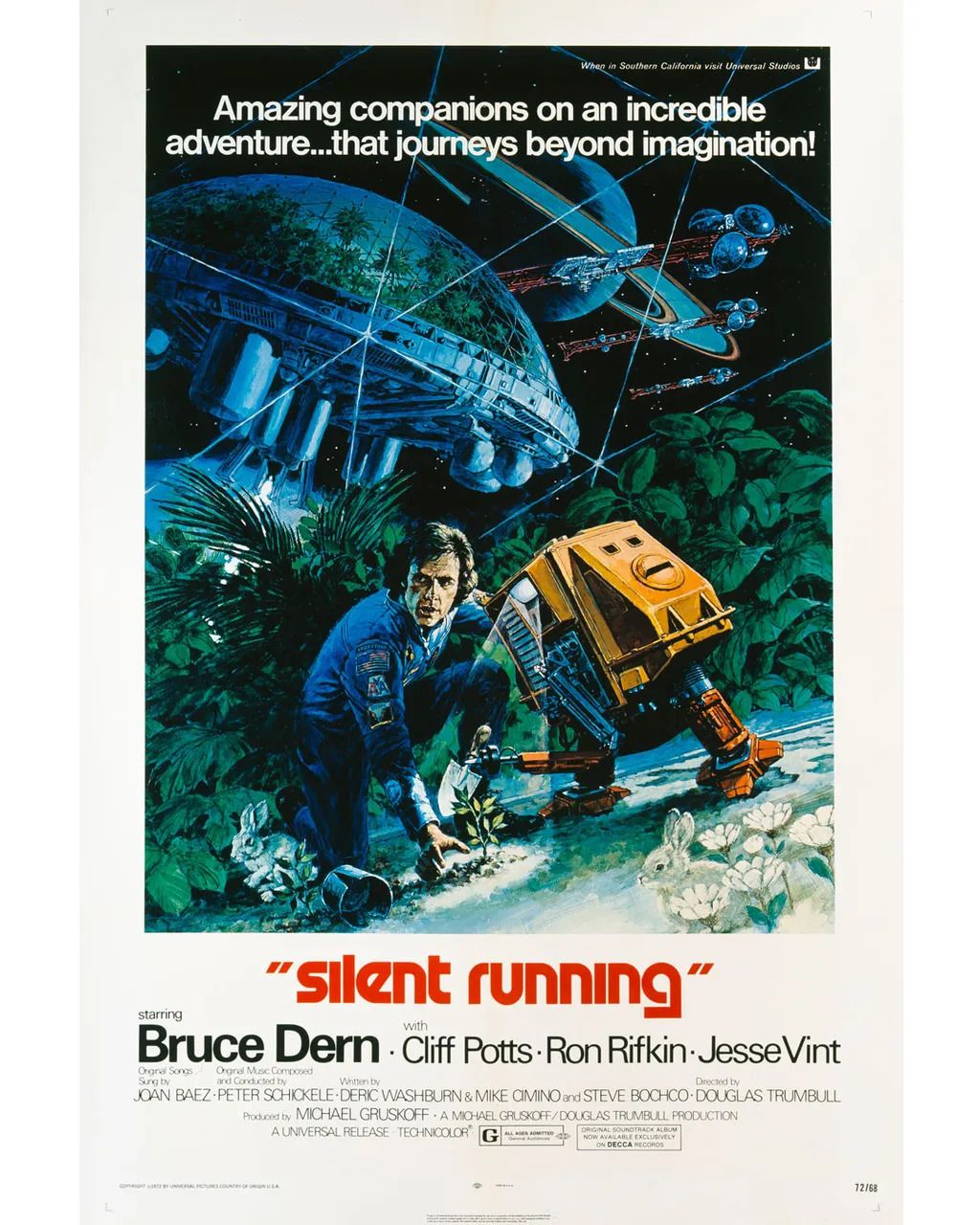

Released in 1972, Silent Running was a kitsch take on the space movie. Lewis Gordon explores how the film anticipated 21st-Century technology.

Silent Running opens with an exquisite close-up of brightly coloured flora and slowly moving fauna. The forest is glistening wet – like it's covered in rainfall – but parts of the path are metal, and the starlit sky is framed by triangular bars. The camera slowly reveals this isn't untouched wilderness but a flourishing garden within a giant geodesic dome. A few moments later, the camera zooms out, spectacularly revealing the giant greenhouse is actually one of six located on a spacecraft gliding through space. Even in the darkest depths of the cosmos life persists, but the prominent branding emblazoned on the ship's exterior suggests this isn't a utopian project; far from it, this nature is the property of a freighter megacorporation.

Within the pantheon of great sci-fi from the 1960s and 1970s, Silent Running (1972) is often overlooked. Stanley Kubrick's totemic and philosophical 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) arguably defines the period while Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), signaled a shift towards broader popcorn sensibilities. Douglas Trumbull provided visual effects for each of these big-budget classics but as a director, the comparably kitsch Silent Running was his own idiosyncratic take on the space movie. Its shoestring $1 million budget makes its visionary first few minutes all the more remarkable while an emotional core brims with the big-hearted idealism of the era's countercultural politics. It's goofy, moving, and awe-inspiring – often within the same scene; nearly 50 years on, Silent Running's charms remain undimmed.

The film was bankrolled by the success of Dennis Hopper's seminal 1969 road movie Easy Rider. Keen to capture the imagination of a newly politicised generation and, in return, reap comparable box office success, Universal studio executives pumped profits from Easy Rider into five youth-oriented movies, including American Graffiti. But praise for Trumbull's film, arguably the most conceptually and practically ambitious of the productions, was muted; the New York Times described it as "too simple-minded to be consistently entertaining" while Gene Siskel, writing in the Chicago Tribune, referred to it as a "poor man's 2001: A Space Odyssey".

Gentle radicalism

Other reviews, however, hint at Silent Running's enduring strengths. The Los Angeles Times applauded the film's "fable-like" quality and "admirable simplicity". True enough, Silent Running's set-up is a model of efficiency; a mission control transmission relays that the freighter carries the last of Earth's precious plantlife. When orders arrive to detonate the forests using nuclear bombs – part of a corporate cost-cutting exercise communicated via another clinical transmission – Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern), the film's plant-loving protagonist, sets in motion a series of events to save the arboreal cargo. Unable to compromise on his conservationist principles, Lowell murders his resistive crewmates. The moral ambiguity Dern sustains – both an admirable and unsettling presence – is central to the film's intrigue.

In the post-apocalyptic sci-fi, Dern's character reprograms his spaceship's service robots to plant trees and play poker

In the post-apocalyptic sci-fi, Dern's character reprograms his spaceship's service robots to plant trees and play poker

Silent Running's ongoing appeal is owed, in part, to the prescience of this ecologically-inflected premise. In 1972, global warming was over 15 years away from entering popular discourse (that happened during a 1988 address to the US Senate) but a popular environmental campaign was already in full swing. In 1970, Santa Barbara celebrated Environmental Rights Day, a one-year commemoration for a devastating oil spill. A few months later, the first Earth Day took place across US colleges, universities, schools, and communities. These events, landmark awakenings of public consciousness, emerged in the path of Rachel Carson's watershed 1962 eco-treatise, Silent Spring (which shares an eerie resonance with the title of Trumbull's film). Indeed, cinema-goers hungry for insight into the sickened planet Earth which Silent Running only hints at would have been well-served by the desolate opening of Carson's book:

"The roadsides, once so attractive, were now lined with brown and withered vegetation, as though swept by fire. These, too, were silent, deserted by all living things. Even the streams were now lifeless. Anglers no longer visited them, for all the fish had died."

An instrument of US imperial power was transformed into the set of an anti-establishment movie; a tool for human and environmental misery was reappropriated for artistic and ecological ends

Surprisingly, the film's central environmental angle emerged throughout production. "The original treatment didn't have an environmental theme at all – it was about alien contact," said Trumbull in an interview. "It was the '60s – it was during the Vietnam War wind-down. Everybody was very environmentally conscious." There's perhaps a subtle anti-war sentiment hidden beneath the film's verdant greenery and sleek futurism, not just in its critique of nuclear weapons (used to destroy the last-remaining vegetation) but embodied in the set – that of the giant freighter called Valley Forge. Because of budgetary constraints, it was filmed on a decommissioned military aircraft carrier rather than in a studio, resulting in an unexpected symbolic flourish. An instrument of US imperial power was transformed into the set of an anti-establishment movie; a tool for human and environmental misery was reappropriated for artistic and ecological ends.

The director would only helm one further feature, the brain-computer interface thriller Brainstorm (1983), a film mired in tragedy following the death of its star Natalie Wood during production. Most of Trumbull's post-Silent Running work involved special effects, notably on Ridley Scott's 1982 cyberpunk classic Blade Runner and Terrence Malick's sprawling metaphysical drama The Tree of Life (2011). The latter, in particular, introduced Trumbull to a modern audience via the film's breathtaking and psychedelic "universe" sequence; fluorescent dyes, flares, paints, and chemicals were transfigured into the very essence of dawning, celestial life – an analogue approach to a question of intense otherness.

The film's interiors were filmed aboard a decommissioned Korean War

aircraft carrier docked at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard in California

The film's interiors were filmed aboard a decommissioned Korean War

aircraft carrier docked at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard in California

Silent Running is similarly inventive, although Trumbull's focus on nature sits alongside that of machinery. The film courses with an irrepressible techno-optimism which, compared to the modern backlash against tech companies, feels almost quaint. "Part of Silent Running's theme is the relationship between Dern and his drones," Trumbull explained, referring to the three helpful robots Lowell increasingly relies upon. "It's not 2001: A Space Odyssey – machinery isn't malevolent – they're simply tools." During the film's second act, Lowell teaches the robots – affectionately named Dewey, Huey, and Louie – how to plant trees, effectively reengineering their function towards environmental good. These robots, often treated by critics as little more than a cute addition, might in fact prove to be the film's most influential aspect, helping anticipate a new configuration of machine-assisted wilderness.

The film's greatest visual trick is its simplest; framing the lush foliage against the pitch black of the universe and whirring machines makes organic life all the more miraculous. By the end, nature has been spared destruction; to an extent, it has been emancipated. One of the final shots – that of the lonely droid Dewey diligently caring for the plants – evokes another counterculture work, writer Richard Brautigan's 1967 poem, All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace. "I like to think of a cybernetic meadow," it begins. "Where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony, like pure water touching clear sky." This appears in tune with Trumbull's heartfelt, ecological take on sci-fi. Silent Running's gentle radicalism and hopeful vision of nature and technology will feel corny to some, but to me, it's positively cosmic.