Teresa Cheng says details of decisions based on national security and intelligence will not be disclosed, but other matters can still be challenged in court by affected individuals.

A vetting committee set up under Beijing’s overhaul of Hong Kong’s electoral system to screen out candidates deemed “unpatriotic” will consider previous actions and words by an individual, the city’s justice minister has said, adding however that disqualifications may not necessarily indicate a breach of the national security law.

Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah said the new committee would receive advice from police’s national security unit and a commission led by the chief executive and supervised by Beijing, before making a decision. The move could still be subject to appeal in court if it did not involve intelligence.

Decisions related to “national security reasons” would be kept secret and not made public when determining someone’s eligibility to be a candidate in elections, she added.

“The committee will definitely take the advice of the commission for safeguarding national security seriously, as they are the experts and most familiar with the issue [on patriotism],” she told a radio programme on Saturday.

The vetting committee, comprising principal officials, will have the power to decide who can run in elections under sweeping changes to the city’s political system approved by Beijing on Tuesday.

Cheng said current laws in Hong Kong did provide “objective standards” to determine if a candidate pledged allegiance to the government and the Basic Law, citing the “positive and negative” lists set out under the proposed oath-taking bill for public officials, legislators and district councillors.

Committing acts that endangered national security, or that “undermine or have a tendency to undermine the overall interests” of Hong Kong would be considered unpatriotic under the new lists.

“All available information about a candidate should be reviewed before making a judgment,” the justice minister said. “We cannot limit ourselves and say we will only review a person’s words and deeds in the past three to five years … Maybe something he or she mentioned 10 years ago has a connection with what that person advocates today.”

But Cheng also highlighted that a candidate deemed “unpatriotic” and banned from elections did not necessarily mean the person had violated the national security law.

“Under Article 63 of the Basic Law, it has to be the Department of Justice (DOJ) to determine independently whether a person has violated any law, and if there is a reasonable opportunity for conviction. The vetting committee’s work on reviewing allegiance cannot be identical to the DOJ’s duties,” she said.

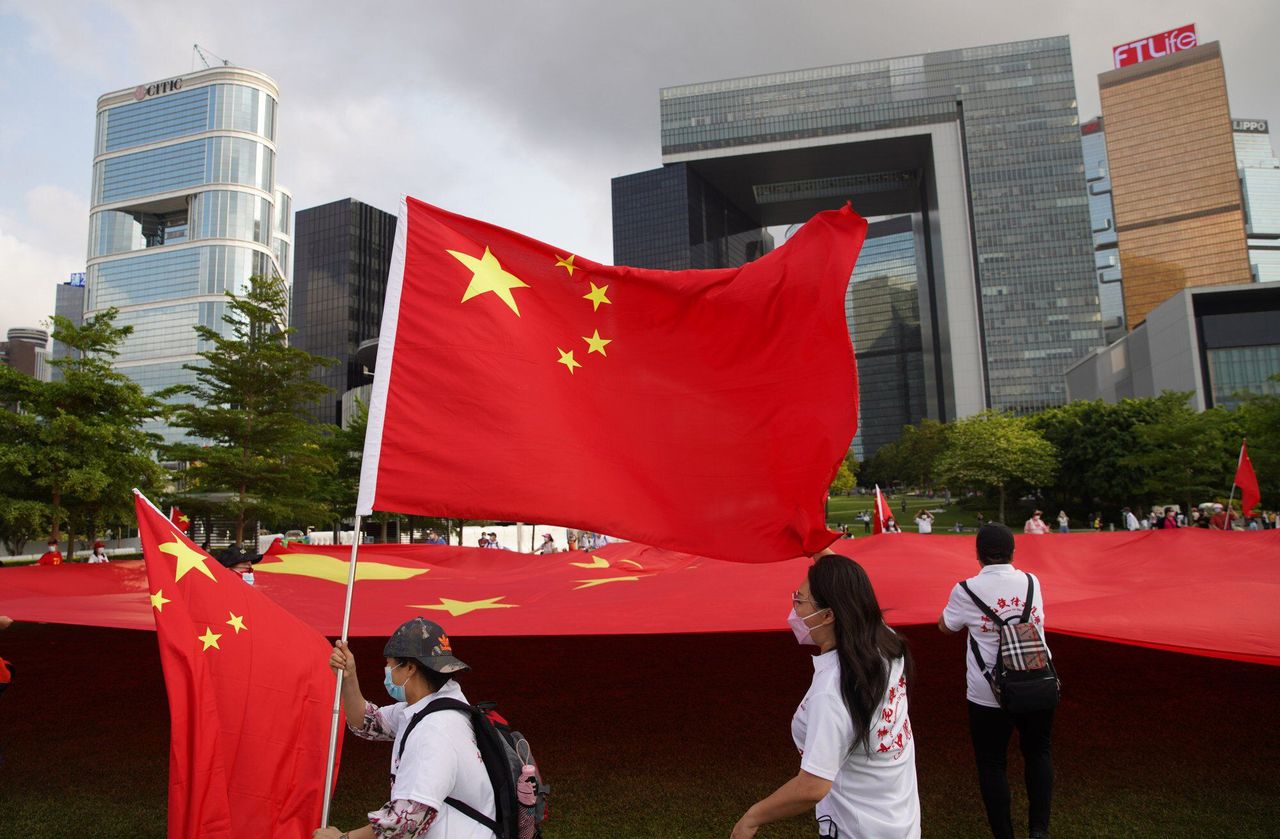

People wield the national flag in Hong Kong’s Tamar Park, in support of Beijing’s electoral reforms.

People wield the national flag in Hong Kong’s Tamar Park, in support of Beijing’s electoral reforms.

Earlier, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor said the vetting committee’s decision could not be judicially challenged.

On this point, Cheng said only decisions made by the police’s national security unit and the committee for safeguarding national security would be kept secret and not subject to judicial review.

“For general requirements, such as if there is a problem with the right of abode, the candidate can still raise related challenges,” Cheng said. “Only if the disqualification is related to national security reasons, then it would be kept secret and not undergo an appeal.”

She said such a decision aligned with articles in the security legislation that stipulate the non-disclosure and barring of lawsuits on matters of intelligence.

Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang Kwok-wai, on the same radio show, also said: “There would be a remark saying ‘national security reasons’ in the candidates’ form, but details would not be disclosed.”

On whether there would be conflict of interest for the chief executive as she chairs the national security commission, Cheng said the body was under the supervision of the central government and involved many officials, therefore “it will not be that anyone can have the final say”.

Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang.

Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang.

But legal scholars and opposition camp veterans said more justification was needed for Cheng’s explanation on not granting any appeal.

Simon Young Ngai-man, who specialises in constitutional law at the University of Hong Kong, said people knew from experience, such as with the Commissioner for Interception and Surveillance, it was possible to have an independent review mechanism with secrecy measures to protect the relevant public interest.

“Having senior public officials make potentially controversial decisions that shut out candidacy in an election will necessarily raise questions of whether the person is being discriminated against for their political opinions,” he said. “To justify this as a necessary and reasonable derogation will require the government to show that having an independent review mechanism with secrecy measures is not feasible. I have yet to see such a justification.”

Former Democratic Party chairwoman Emily Lau Wai-hing said the retrogression power was “very threatening” to all candidates, while it was concerning that candidates might never know the true reasons for being disqualified.

“So it’s more like a system that the government has all the control,” Lau said. “It is not worthwhile taking part in these elections, as no one knows about the criteria, while one may have to bear the consequences of being doxxed and investigated by the national security unit.”

But Albert Chen Hung-yee, a legal scholar at HKU specialising in the intertwining of Hong Kong and mainland legal systems, said any decision passed through the committee for safeguarding national security could not be subject to legal challenges under national security legislation.

He agreed the new arrangement would transfer the traditional role of judges, who had ruled in cases that required them to decide whether a candidate would uphold the Basic Law, entirely to law enforcement officials, but the court could still rule on challenges surrounding the Legislative Council Ordinance, “such as whether the candidate has lived in Hong Kong long enough”.

As part of the revamp, the Beijing-controlled Election Committee is empowered to both field representatives of its own to the legislature and nominate those from outside their ranks, with seats on the body expanded from 1,200 to 1,500.

All 117 district council seats in the Election Committee were also scrapped, and replaced by newcomers including members of Area Committees, District Fight Crime Committees and District Fire Safety Committees – municipal-level bodies often dominated by the pro-establishment camp.

Asked if the district councillors – a group currently dominated by the opposition camp – might be allowed to rejoin the Election Committee in the future, Tsang said “it depends on whether they would return to the right track”.

“The district councillors are excluded as there has been serious pan-politicisation in the group. They fought for their political demands and failed to serve districts well, thus the central government decided to withdraw their political power,” he added.