Hong Kong has all along considered one country, two systems as a way to set ourselves apart from the rest of the country. In contrast, for Macau and Beijing, the principle is about integration and convergence.

My guess is that no one in Beijing lost any sleep over Macau’s Legislative Assembly elections yesterday. And they shouldn’t. There were no surprises. It is the least contested election in Macau with only 14 electoral lists competing for 14 directly elected seats.

It didn’t start out that way. Nineteen lists consisting more than 150 candidates were running until five lists and 20 candidates were disqualified after the Electoral Affairs Commission found that they had been disloyal to Macau and unsupportive of the Macau Basic Law.

And as a result, only one token pro-democracy candidate list – led by the very mild Jose Pereira Coutinho – remained.

And so if any of us here in Hong Kong are wondering what our Legislative Council elections, scheduled for the end of the year, will be like, look no further than Macau. We should be looking at Macau because it is now the exemplar of “one country, two systems”, showing Hong Kong a political path that would not incur Beijing’s wrath.

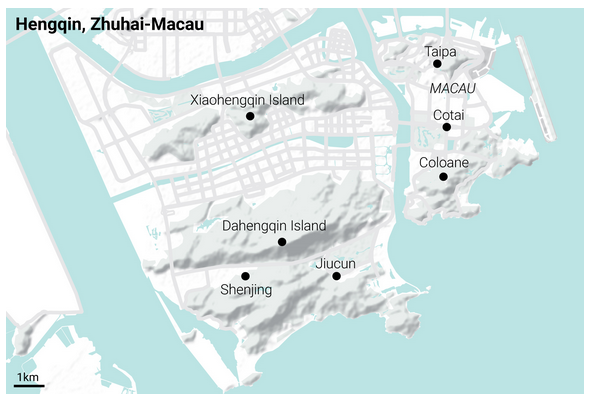

Not only that, Macau is also going where Hong Kong has never gone before: it is being tasked with running its system within the other system. Specifically, Beijing’s new plan for Hengqin, an island in Zhuhai being transformed into an economic zone, calls for Macau to run one country, two systems there, and that’s huge.

Once upon a time, it was hoped that Hong Kong would prove that one country, two systems was the best way forward and facilitate what would ultimately be the country’s reunification.

Visiting Macau in 2019, President Xi Jinping said that it is Macau that has provided “a gorgeous chapter” in the short history of the one country, two systems experiment. Macau chief executive Ho Iat-seng: “Macau will be an example of China’s reunification.”

And so it is the “Macau model” that the country has embraced, and it is Macau that is being allowed to take the lead ahead of Hong Kong.

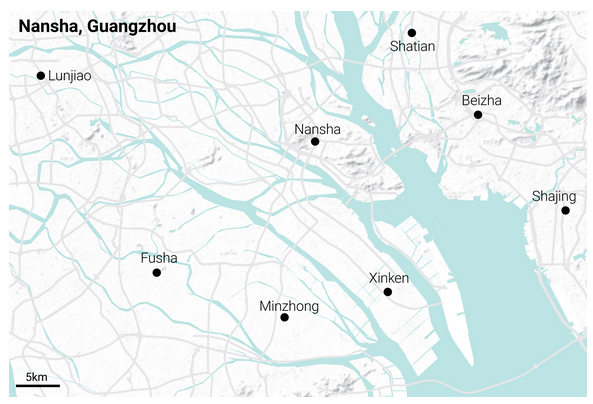

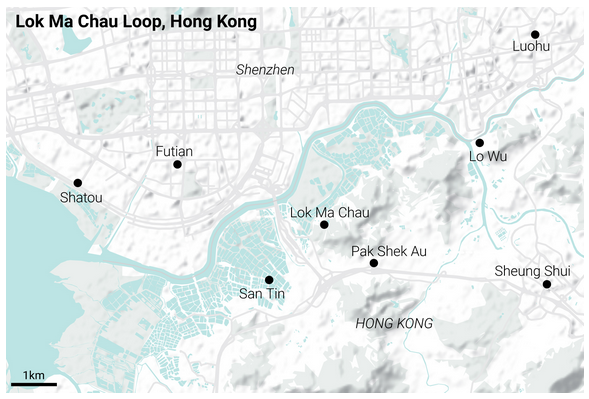

Beijing’s master plan for integration includes Hong Kong, to be sure, so this is no time for sour grapes. Compared with the role envisioned for Macau in Hengqin, however, Hong Kong’s proposed role in Qianhai, an economic zone in Shenzhen, is more indicative of Beijing’s desire to rein in Hong Kong. Hong Kong must accept that it is part of a much larger picture, take into account what the country is doing, and fit in.

In other words, to enjoy the backing of the country, we are no longer free to turn our backs on it.

Hong Kong Chief Secretary John Lee Ka-chiu speaks via a video link at a

press conference on the development of Hengqin and Qianhai held at the

Information Office of the State Council in Beijing on September 9

Hong Kong Chief Secretary John Lee Ka-chiu speaks via a video link at a

press conference on the development of Hengqin and Qianhai held at the

Information Office of the State Council in Beijing on September 9

Hong Kong has all along considered one country, two systems as a way to set ourselves apart from the rest of the country. That kind of thinking set us on a diverging path. In contrast, for Macau and Beijing, the one country, two systems principle is about integration and convergence.

For those who have been complaining about “mainlandisation”, take note of Beijing’s treatment of both Hong Kong and Macau. Beijing is serious about integration, about inviting the two cities to contribute, to play distinct roles, albeit in very different ways.

Last week, a press conference brought together senior Beijing officials and Greater Bay Area representatives to sell the central government’s plan to expand Qianhai, which would be an opportunity to collaborate with Hong Kong in areas including technology and finance.

Again, Beijing is not talking about taking over or overpowering us. It is extending to us an invitation to interact with, engage with, and have an impact on the rest of the country.

The Hong Kong model of one country, two systems veered off course, and hit a rut over our differences. An overemphasis on how different we are from the rest of the country made it hard to see common ground, find common interests and collaborate.

Some of us may not like Beijing’s aversion to political surprises, but it doesn’t mean we need to keep pushing its buttons.

As long as Beijing doesn’t swoop in again to clean up after us politically, we can surely map out a brighter future for one country, two systems.