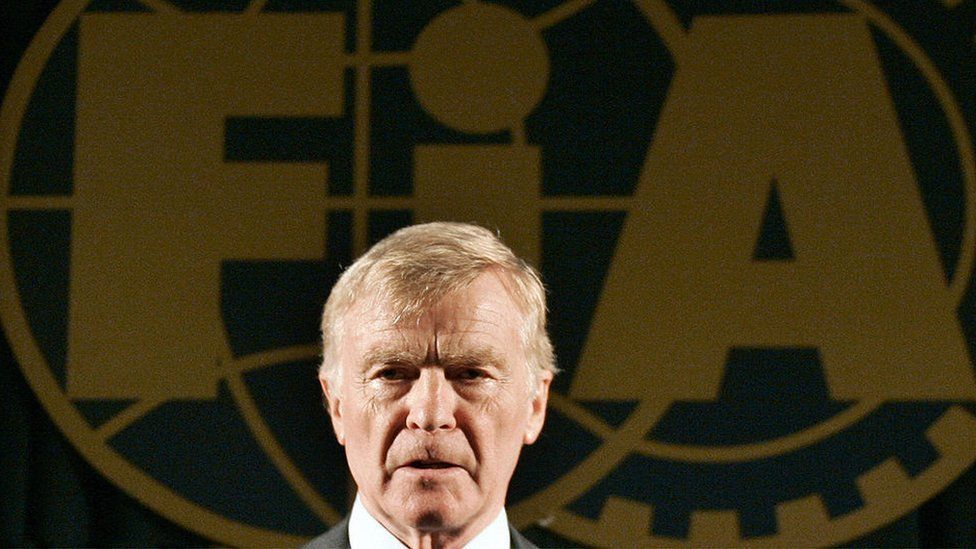

Former motorsport boss Max Mosley, who later became a privacy campaigner, has died aged 81.

Ex-Formula 1 boss Bernie Ecclestone said it was "like losing a brother".

Mr Mosley, who had been suffering from cancer, led motorsport's governing body the FIA from 1993 to 2009.

He also campaigned for tighter press regulation after winning £60,000 damages from the News of the World when it wrongly published a story alleging he had attended a Nazi-themed orgy.

Mr Mosley, in his role as FIA president, initiated widespread reforms of safety procedures in Formula 1 following the death of Ayrton Senna in 1994.

Mr Ecclestone added: "He did, a lot of good things not just for motorsport, also the [car] industry. He was very good in making sure people built cars that were safe."

Current FIA president Jean Todt said in a tweet he was "deeply saddened" by the news, adding that Mr Mosley "strongly contributed to reinforcing safety on track and on the roads".

Meanwhile, a spokesman for F1 described Mr Mosley as "a huge figure in the transition" of the sport.

Privacy campaign

Mr Mosley - the son of 1930s British fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley - took his privacy action against Sunday tabloid the News of the World in 2008 over the paper's story.

The newspaper had secretly filmed him with five prostitutes and later published a front-page story.

A judge ruled there was no substance to the allegation that there had been a Nazi theme to the sex party and found that his privacy had been breached. The High Court also said the article was not in the public interest.

Although Mr Mosley was awarded damages, everyone had learned the details of his sexual preferences, and he argued money alone could not restore his reputation.

He went on to seek reform of celebrity privacy laws, making a bid in 2011 for newspapers to warn people before exposing their private lives.

His case was unsuccessful, but it led Mr Mosley to use some of his family fortune to support victims of the Fleet Street phone-hacking scandal.

He also backed the independent press regulator Impress through a family charity, which Mr Mosley set up in his son Alexander's memory, after he died in 2009.

Mr Mosley said in 2011 that the story had a "very bad effect" on Alexander, whose death was ruled as being due to non-dependent drug abuse.

Impress chief executive Ed Procter said Mr Mosley improved access to justice for victims of press misconduct and put "his own resources behind efforts to ensure that these issues will not be forgotten".

Hacked Off, which was set up in response to phone-hacking, said it was thanks to Mr Mosley's "courage and generosity that the movement for a more ethical press remains so effective today".

And media lawyer Mark Stephens, who represented phone-hacking victims, described Mr Mosley as "effectively the author of modern privacy law".

'A dizzying intellect and an intimidating man'

Max Mosley was one of the most influential and important figures in motorsport over the last half-century - and also among the most controversial.

With a brilliant intellect and a devious, sometimes malicious mind, he was arguably better suited to a career in politics.

But he was the son of the 1930s British fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley, and in his youth was involved in his father's post-war political party the Union Movement. He realised his personal history would prevent him from entering Parliament, so he directed his attention towards motorsport instead.

Mosley was a fascinating and contradictory character. Urbane and charming, he was never less than engaging on a personal level.

But not everyone felt so kindly towards this patrician and sometimes patronising figure. Mosley had a vindictive streak. His political and legal abilities were widely admired, but not everyone found him easy to like.

Born in London on 13 April, 1940, Mr Mosley studied physics at Christ Church, Oxford, and later turned to law and became a barrister.

After a brief career as a racing driver in the late 1960s, in which he rose to race in Formula 2, he co-founded the racing car constructor March in 1970 with Robin Herd, Alan Rees and Graham Coaker - the company name formed from the initial letters of their surnames.

The company won its first three Formula 1 races in 1970 and later diversified into other forms of motorsport, but by the end of 1977 Mr Mosley had left the company to work full-time in motorsport politics.

He joined forces with Bernie Ecclestone at the Formula 1 Constructors' Association (FOCA) and the two fought a bitter political war for control of the sport with the governing body, then called FISA, in 1980 and 1981.

The arguments were finally settled with the so-called Concorde Agreement, which essentially set up the structure of the sport that remains in place to this day - FOCA, later to be renamed F1, held the commercial rights, while FISA controlled the rules.

Mr Mosley left motorsport in 1982 to work for the Conservative Party but returned four years later to become president of the FISA manufacturers' commission.

He used the role as a springboard to launch a bid for the presidency of FISA in 1991. Mr Mosley then became president of its parent body the FIA, the international automobile federation, when the two were merged in 1993.

He quickly established a modus operandi as a president who was proactive, provocative and controversial.

In 1993, he instigated a ban on driver aids such as traction control and active suspension against the wishes of the teams. And his combative approach, in which he used a vast intellect to devise clever strategy and often Machiavellian tactics, continued over his near two-decade stay in his role.

His biggest challenge came a year later, when Ayrton Senna was killed in an accident at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix that was broadcast live around the world - just 24 hours after Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger died in a crash during qualifying for the same race.

As a global sporting icon, and an almost God-like figure in his native Brazil, Mr Senna's death raised serious questions about safety in Formula 1, and world leaders contacted Mr Mosley questioning the sport's position.

Recognising the threat to the sport's existence, Mr Mosley introduced a series of changes to the cars, setting in motion a new approach whereby the safety of the drivers and spectators was central to the ethos of motorsport and attempts were made to constantly improve it.

In this, he was backed by Mr Ecclestone, and supported by the FIA medical delegate Professor Sid Watkins and the FIA F1 director Charlie Whiting. Together they changed the face of the sport.

As FIA president he also turned his attention to road cars, and was central in introducing the EuroNCAP crash testing programme.

This required manufacturers to meet minimum safety standards in their cars for the first time and has played a significant role in reducing the number of deaths in road accidents.

Teams' revolt

But the longer Mr Mosley remained in situ, the more F1 teams began to become uncomfortable with what they saw as an authoritarian and arbitrary approach, along with sometimes questionable methods and motives.

Mr Mosley's reputation with the F1 teams was badly damaged by his deal to remove the TV rights to F1 from Foca and sell them on a 100-year lease to Mr Ecclestone's companies for what many considered to be a paltry one-off figure of $360m in 1995.

His antagonistic style of running the sport continued through the 2000s and the beginning of the end of his time at the FIA came with the News Of The World's story.

He survived the initial outcry but when in 2009 he tried to introduce a budget cap into F1, the big teams had had enough.

The latest of many political fights began, and this time Mr Mosley lost. The major teams and car manufacturers threatened to set up a rival championship, and to bring them back into the fold Mr Mosley had to agree not to seek a further term as president when his latest one expired in October 2009.