How the eclectic collections that combine botanical know-how and creativity are bringing nature indoors. Dominic Lutyens takes a glimpse into the collectors' intriguing worlds.

Homes filled with objects culled from the natural world – from gnarled bones and flamboyant feathers to twisted twigs and taxidermy – are increasingly common, as a new book highlights. The New Naturalists – Inside the Homes of Creative Collectors by Claire Bingham features domestic interiors adorned with objects casually picked up in parks or on beaches or acquired at flea markets and fairs. "The book looks at homes from all over the world – different collections and aesthetics – with each story bound to one person or couple's obsession for collecting, and a magpie urge to acquire," Bingham tells BBC Culture.

This fascination with natural history has its historical precedents, she points out: "There's a long history of collecting from nature. In the 16th Century, a craze for shells saw wealthy European landowners charter ships to the New World to bring back items of curiosity." An early example of the phenomenon in the UK is the 17th-Century, shell-lined underground grotto at Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire. "Collecting isn't just driven by science or a desire to catalogue. It's also about an appreciation of beautiful forms," adds Bingham.

Horticulturalist Sean Barton's home is among those featured in the book The New Naturalists

Horticulturalist Sean Barton's home is among those featured in the book The New Naturalists

Owning natural objects that have changed little in centuries perhaps represents a desire to retreat from modern life. Among some homeowners, a passion for amassing these presents an opportunity to bring raw nature indoors and reject the convention of clinical, tidy homes.

According to Bingham, a desire to connect with nature during and in the wake of lockdowns has intensified this fascination with natural history. "We've all been cooped up in smaller worlds. By seeking out spaces where we've been able to, new relationships with nature have been paramount."

The compulsion to deck out homes with natural history is often ignited by childhood memories of collecting striking stones and bones in the great outdoors

Artists who gather natural history in their homes often do so because it provides materials – and inspiration – for their work. Their organic, often surreal artworks are frequently displayed alongside natural objects, forming a harmonious whole.

Barton's home is a reflection of his natural history obsession, and is full of rare plants and taxidermy

Barton's home is a reflection of his natural history obsession, and is full of rare plants and taxidermy

But regulations apply to collecting such objects, Bingham points out: "To forage sustainably and responsibly, stick to your garden or to items that have fallen to the ground or died. Only collect from plentiful populations. It's illegal [in the UK] to dig up or remove plants in public gardens and parks. All taxidermy should come from a licensed dealer."

As the book reveals, the compulsion to deck out homes with natural history is often ignited by childhood memories of encountering taxidermy in shops or museums, or of collecting striking stones and bones in the great outdoors.

Horticulturalist Sean Barton, whose home is featured in the book, traces his interest in natural history back to childhood holidays in Wales: "There was a shop in Tenby, south Wales that sold taxidermy, and I always came home with a stuffed snake or puffer fish," remembers Barton, who collects rare plants as well as taxidermy, the latter often bought at auction.

Natural history buffs usually find older, ornate interiors with rich, dark wall colours better suited to displaying natural objects, rather than colder, clean-lined rooms. And they like an atmosphere that triggers memories of museums. "I love the smell of museums, their wood panelling and old books. I painted my hall a mahogany brown," says Barton, who is obsessed with orchids, which he displays with ferns, terrariums, antlers, taxidermy and shells.

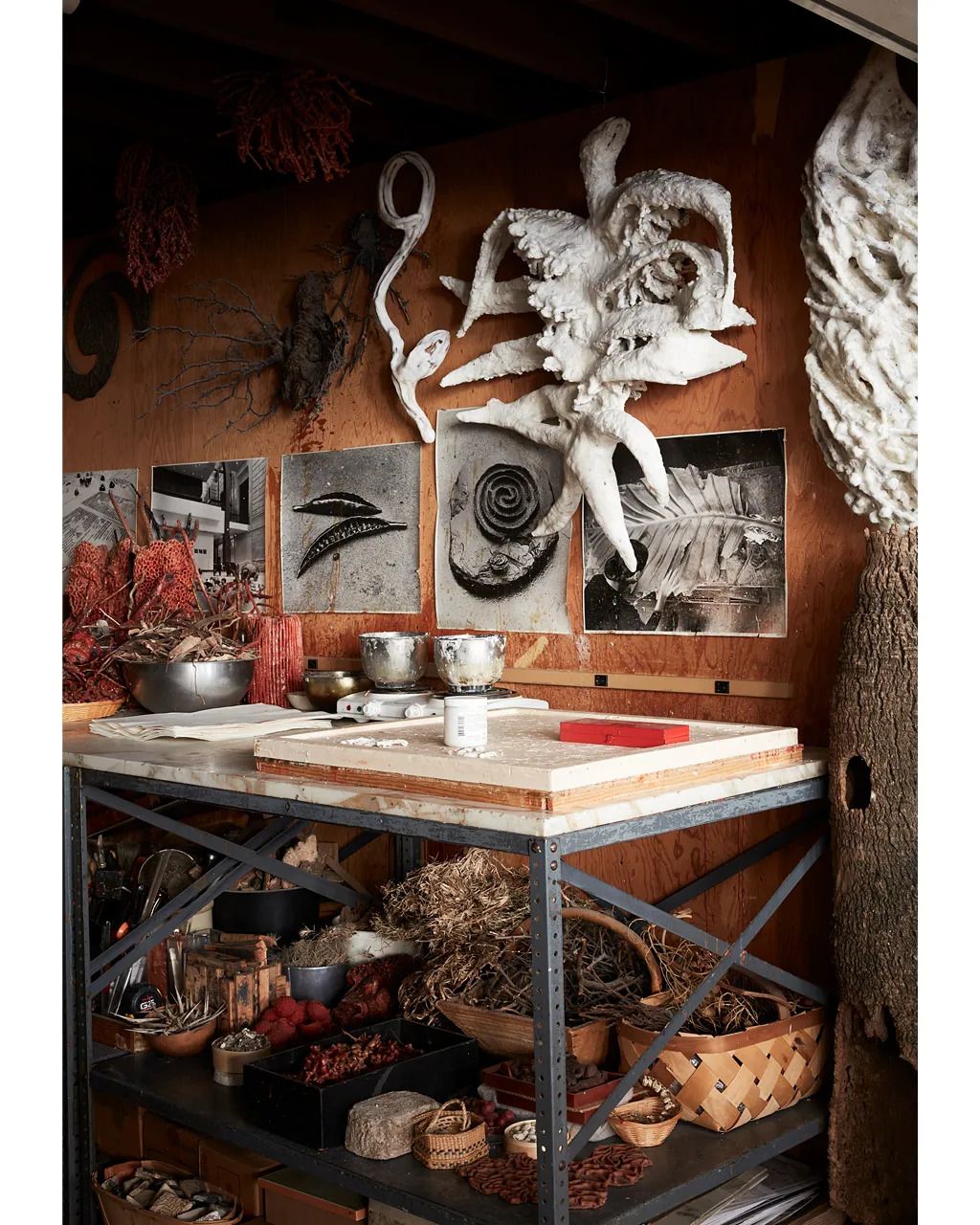

Michele Oka Doner's New York apartment reflects her love of natural objects, inspired by her childhood by the sea in Miami

Michele Oka Doner's New York apartment reflects her love of natural objects, inspired by her childhood by the sea in Miami

Barton used to live in a semi-detached, 1990s home before moving to a Victorian gatehouse in Macclesfield, Cheshire in the UK. "Living in a new-build box didn't work with the antlers and other stuff," he says. "My house now suits my collections. High ceilings help. I love drab tones that work well with – and don't compete with – natural history and plants. When I moved here, the walls were dazzling white and powder blue and felt like an igloo. I spent days scraping off thick, white gloss paint."

Nature's way

By contrast, the New York home of artist and writer Michele Oka Doner, also included in the book, has industrial roots. A former button factory in SoHo, it has high ceilings, tall windows and mostly pristine white walls, although wedding cake-like Corinthian columns give the mainly open-plan space a warm, old-world quality.

Her interest in natural objects was sparked by growing up in Miami Beach, and today her home houses a fragment of bark from the oldest baobab tree in Kenya as well as fossils embedded in a console's marble top. Her art often incorporates or depicts natural history. One of her best-known pieces – the public installation, A Walk on the Beach, at Miami International Airport – is a terrazzo walkway inlaid with mother-of-pearl and bronze. Several of her artworks hang in her home, from a section of a huge drawing of mother-of-pearl seen under a microscope to her wax-coated sculpture, Primordial Creature.

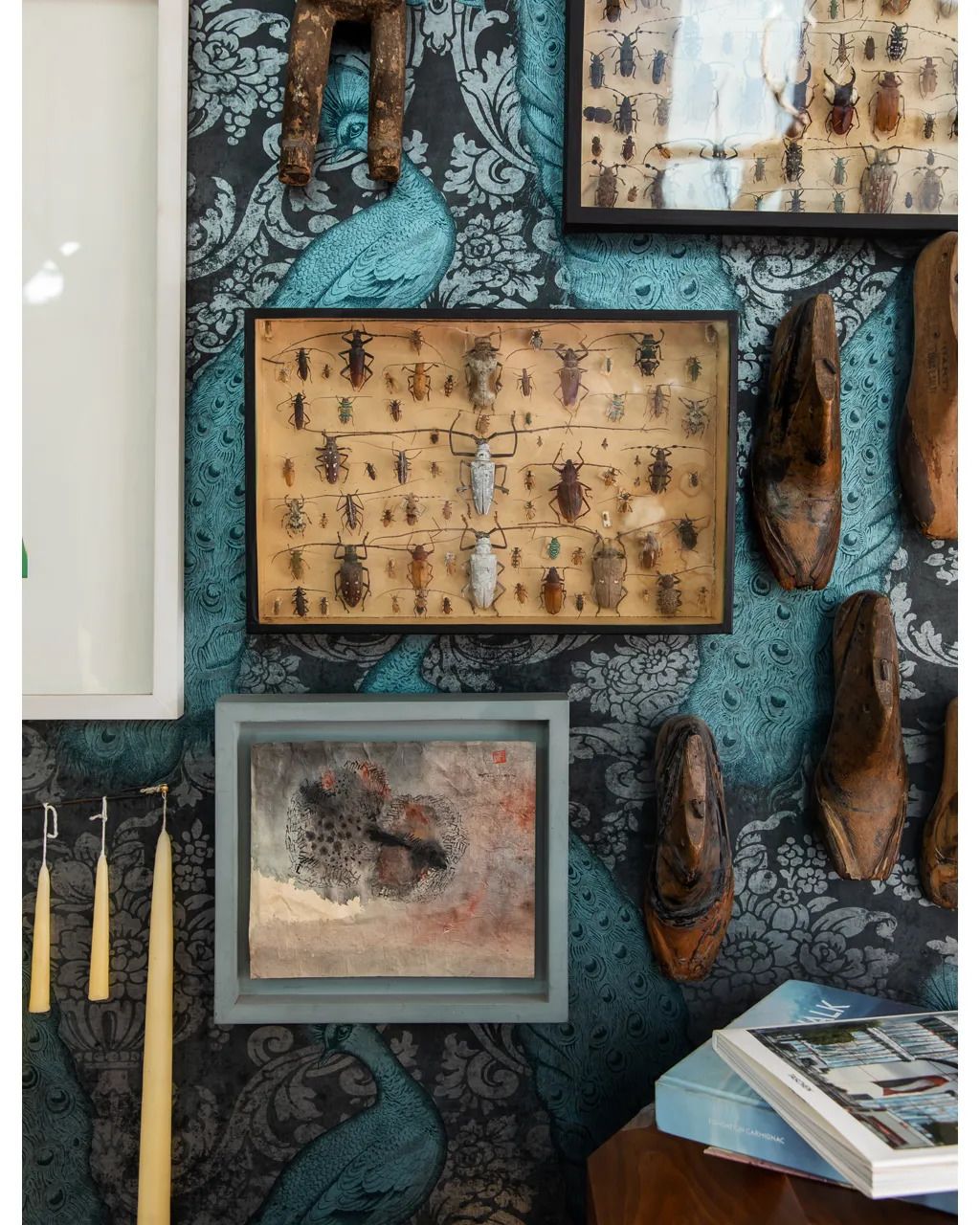

French sculptor Zoé Rumeau's work is heavily influenced by her love of natural materials

French sculptor Zoé Rumeau's work is heavily influenced by her love of natural materials

It's perhaps surprising that one so drawn to natural history should live in a city. Quizzed about this, she says, "I believe cities are a natural space," adding that nature has become more present in Manhattan ever since New York took part in the Million Tree Project, which set a target for planting one million trees in the city. "There are wonderful moments with the new trees in my neighbourhood as a leaf unfurls or a bud flowers – sometimes a strong wind removes a souvenir to take home."

Some of the homeowners profiled in the book acquire specific categories of natural objects, others take a more inclusive, relaxed approach, resulting in an eclectic assortment of items, often arranged by eye. Barton falls into the second camp: "I think natural objects just work together naturally," he reasons. "Animal-wise, I've got reptilian creatures, mainly crocodiles, skulls and antlers."

French sculptor Zoé Rumeau also hoards natural objects in her apartment in Montreuil in eastern Paris. "The area is the Brooklyn of Paris, with lots of artists' studios," says Rumeau, a fan of artist Louise Bourgeois, whose work sometimes incorporated animals' bones. She often buys pieces from Parisian taxidermy specialist Deyrolle and auction house Drouot.

Rumeau likes to display her work and natural objects against backdrops in dark, moody hues, including a baroque wallpaper with turquoise peacock motifs against which hang pinned beetles under glass.

Rumeau houses her eclectic collection in her eastern Paris apartment

Rumeau houses her eclectic collection in her eastern Paris apartment

Her interest in natural forms stems from an unconventional, isolated upbringing, she says: "My parents were hippies who had a house in Ibiza in the 1970s. They had no TV, no friends. As a bored teenager, I began to make things with my hands. Nature inspired me."

Amethyst and malachite gems are displayed along with a fragment of hardened sediment from a river that contains ancient fish fossils

Also featured in the book is the home of Eloise Appel, who once ran a business specialising in educational evaluation, and husband Mark, a former architect. The couple share a passion for gems, stones and fossils, prominently displayed in their ocean-facing house in Playa del Rey, Los Angeles. Amethyst and malachite gems are displayed along with a fragment of hardened sediment from a river that contains ancient fish fossils, dating from the Eocene epoch, 55 million years ago. "We have an eclectic collection," says Eloise, who began acquiring stones aged 10, while growing up in Palm Springs. "Mark likes the geometry of the atomic nature of the stone. I'm mainly attracted to colour and crystal formation."

The couple are not typical natural history collectors, eschewing clutter for clarity. In their modern, minimalist house, their pieces are displayed individually, drawing attention to their sculptural qualities, colours, textures and geometric composition. Most are displayed on stands, some made of transparent Lucite, so the stones appear to float in the air, or on solid plinths like those found in galleries. A slice of agate stands in front of a window. "Translucent crystals look best with sunlight," says Eloise. "Light reflects off the structure of crystals, be it fluorite or metallic pyrite."

The home of Mark and Eloise Appel in Playa del Rey, Los Angeles, features the couple's collection of gems, stones and fossils

The home of Mark and Eloise Appel in Playa del Rey, Los Angeles, features the couple's collection of gems, stones and fossils

She and Mark acquire many specimens from the Tucson Gem and Mineral show in Arizona, the biggest of its kind in the world. "Some pieces come with certification, authenticating their provenance," says Eloise. "Over time, you learn to distinguish the authentic from the man-made. Every year, new fossils and veins of crystals are discovered."

For many collectors, there is no monetary value to the objects they find. They might have caught sight of a fascinating leaf, stone or, more serendipitously, a fossil while strolling in a park or on a beach, then chosen to take it home to add to a burgeoning collection of mementoes. To some, such spaces might appear eccentric and bizarre, but to these homeowners they offer the freedom to explore and pursue their personal obsessions with abandon.