Analysis: the government could generate an extra $20bn by reforming national insurance to tax high earners

The government could generate almost double the £12bn it expects to raise for health and social care if the national insurance system was made fairer, according to a group of economists.

Ministers could fix the system to make higher earners pay the 12% standard rate, handing the Treasury £20bn of extra revenue, according to a team from the London School of Economics and Warwick University.

The analysis found that the government’s failure to reform the national insurance system means that the 1.25% health and social care levy will be a heavier burden on the young while those with property and share assets will continue to benefit from lower tax rates.

This is because Boris Johnson’s hike in tax applies to wages and dividends paid to shareholders, but not to income earned from investments, or to earnings from pensions. The report’s authors calculate that removing the exemptions for investment income and those in receipt of pensions would raise the same amount as the levy is supposed to do – £12bn.

Johnson has refused to rule out further tax rises in the budget next month, which is leading to a growing debate about how fairly the tax burden is being distributed under his government.

The measures, dubbed a “tax on labour” by employers and worker representatives, have raised concerns that the Treasury may seek to cap the UK’s spiralling national debt incurred during the pandemic in ways that increase the unfairness and inconsistency of a tax system, whose architecture dates from more than 70 years ago.

Hannah Thompson, a research fellow at the LSE and one of the authors of the report, said that if ministers wanted to levy a fair tax on incomes, they should increase income tax. If national insurance must be the vehicle, removing the current exemptions for investment income and stretching the 12% band would be fairer.

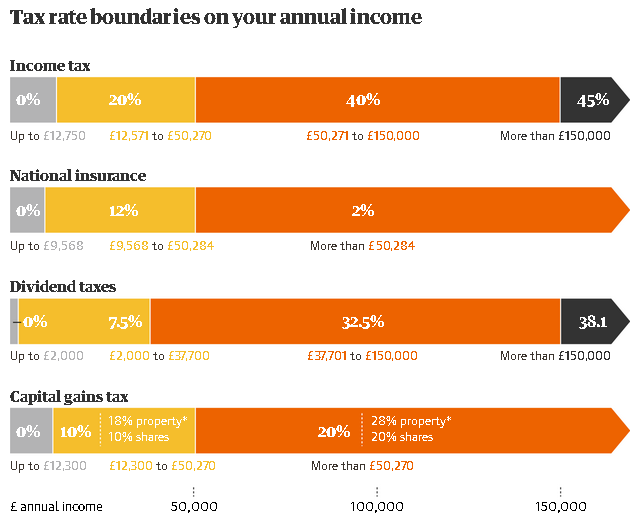

At present, income between £9,568 and £50,284 incurs national insurance at 12%, with any earnings over that taxed at 2%. Thompson said removing the ceiling on the main 12% rate would raise £20bn, allowing ministers to reduce the rate for everyone if only £12bn is required.

“Of course, there are other taxes – capital gains tax and inheritance tax for instance – that could be used, the reforming of which is also long overdue,” Thompson said. “These are often cast aside as not being great revenue raisers, though we argue this is not necessarily true.”

With 25% of pensioners sitting on a household wealth of at least £1m, according to Office for National Statistics figures, it would be possible to generate large sums from inheritance tax. But the threshold of £1m per couple for inherited property wealth means inheritance tax receipts have increased only slightly in recent years.

The government taxes capital gains on shares at 10% and property at 18% up to an income level of £50,270 and at 20% and 28% respectively above this threshold, well short of the 40% higher rate income tax threshold and 45% rate on incomes above £150,000.

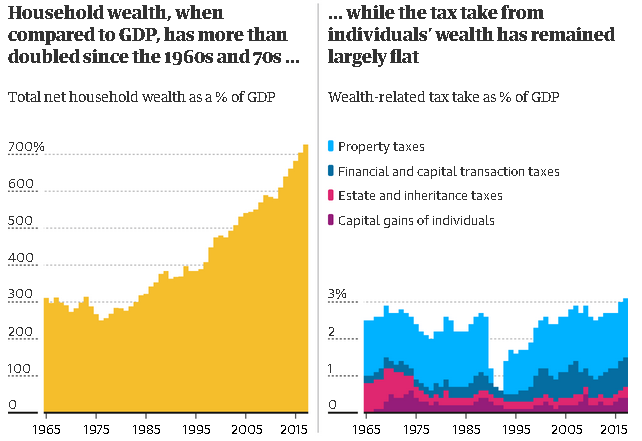

Britain’s wealth has soared since the 1960s from about 300% of annual national income, or GDP, to more than 700%, according to research by the Resolution Foundation. However, while the composition has changed, the overall level of receipts relative to national income has remained at about 3% of GDP for some time, meaning much of the new wealth remains untaxed.

There are calls from across the political spectrum for higher taxes on assets, and property in particular, which accounts for 35% of British wealth, compared with private pensions, which account for 42%.

Torsten Bell, head of the independent thinktank Resolution Foundation, said the government should target well-used exemptions in the capital gains tax regime that save wealthy investors about £8bn a year, including a £2.3bn saving by those who die before their gains are taxed.

“There is big money in the capital gains tax system,” he said.

The left-leaning IPPR thinktank said equalising the tax rate on capital gains with income tax “could generate at least £90bn in extra revenue over five years”.

The Social Market Foundation, an independent thinktank with close ties to the Conservative party, said a 10% tax on the gains from all property sales could generate £410bn over 25 years.

However, taxes on property and pensions are unpopular with older voters, something ministers know from a succession of polls that show national insurance is the least hated tax levied by the Treasury.

In 2002 the then chancellor Gordon Brown levied a 1% increase, again to cover escalating health costs, after he was advised that the public viewed it as a “good tax”.

While a national insurance fund has existed since it was founded by the postwar Labour government and according to its latest accounts has a £37bn surplus, inside Whitehall the fund has been considered largely interchangeable with other taxes for decades, giving the Treasury a free hand to spend cash where and when it likes.

Over the last 50 years, the main rate of national insurance has more than doubled from 5.75% to 12% and will increase to 13.25% once the levy takes effect next April. During the same period the basic rate of income tax has tumbled from 34% to 20%.

As a result, the UK has come to rely less on a progressive income tax system in preference to a flat, regressive system of paying national insurance that targets those on low to middle incomes under the state pension age.