Unaffordable housing is leading to public frustration and resentment, especially among young people, potentially undermining social and political stability. Hong Kong must act to improve affordability and promote greater home ownership among those unable to get on the property ladder.

Hong Kong is ranked among the world’s most expensive cities in terms of property prices. Owning a home in the city has never been as challenging and important. There are serious concerns that unaffordable housing is leading to public frustration and resentment, especially among young people, undermining social and political stability.

Governments worldwide have implemented initiatives to address affordability, subsidising both property rents and purchase costs. Hong Kong introduced the Home Ownership Scheme (HOS) in 1978 to bridge the affordability gap.

Under the scheme, eligible households could buy flats from the government at 30 to 50 per cent below market price and borrow 90 to 95 per cent of the purchase price. The higher-income public housing tenants could attain home ownership and leave public rental flats for those in greater need.

The HOS later extended its coverage from multi-member households to single-individual households, offering greater discounts, improved flat design and fewer restrictions on resale. These measures, along with rising property values, have attracted an increasing number of applicants and helped them to own a home.

The scheme had provided more than 392,000 flats by 2020. Among all households who own flats, more than 32 per cent acquired them through this scheme, according to the Census and Statistics Department.

There is a long-standing policy debate over the benefits of the HOS in Hong Kong. After Hong Kong returned to China, chief executive Tung Chee-hwa announced the “85,000 policy” in 1997, aiming to produce no fewer than 85,000 flats a year and to achieve 70 per cent home ownership by 2007.

However, the plan led to strong resistance from powerful property developers and middle-class homeowners. The economic recession from 1997 to 2003 caused a drop in home prices and seriously undermined market confidence.

To boost the property market, the government suspended the construction of HOS flats in 2003. From 2003 to 2007, fewer than 6,000 surplus HOS flats were sold, representing a 95 per cent reduction from peak sales in the early 1990s.

The debate about the “85,000 policy” and whether the government should intervene in the real estate market has re-emerged since Hong Kong has become the world’s most expensive property market. Although the HOS was relaunched in 2011 as the housing market rebounded, the Hong Kong government decided to minimise intervention by scaling down the supply of HOS flats.

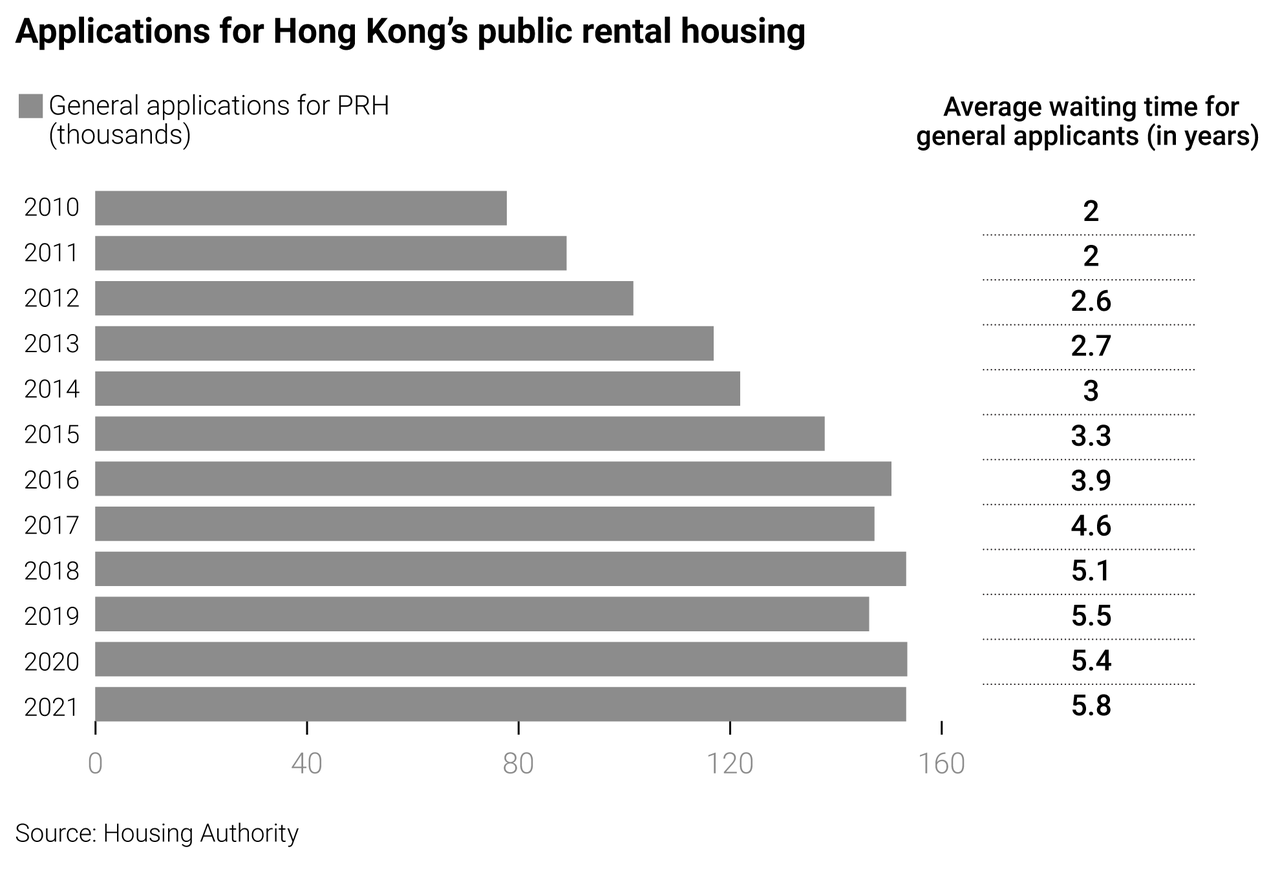

Since demand for HOS flats far exceeds supply, the Housing Authority holds lucky draws to determine who among the eligible applicants can buy a flat. Given the reduced number of available HOS flats after 2003, the chance of winning has dropped steeply. The average success rate for all applicants was about 33 per cent in 2001 but fell to 7.5 per cent in 2015 and just 1.6 per cent in 2018.

The random nature of the lucky draws makes the HOS an ideal experimental setting to evaluate the social consequences of home ownership. As the draw is purely random, statistically we can say that the “winning” and “losing” groups are equal.

The only difference is that the “lucky” group of people become homeowners while the others don’t. The unobserved factors can now be offset. Thus, any statistically significant differences between the two groups can be examined as effects brought about solely by home ownership.

In an article published recently in the sociology journal Social Forces, my co-author Jia Miao and I used the data from the Hong Kong Panel Study of Social Dynamics (HKPSSD), a citywide representative household panel survey from 2011 to 2018. The wide coverage of the samples and random nature of HOS receipt in the HKPSSD allowed us to better evaluate whether pro-ownership housing policies are optimal in Hong Kong and beyond.

Our findings consistently showed that being a homeowner significantly improved life satisfaction and self-assessed class identification. The study results can be generalised to a broader population in Hong Kong.

As housing becomes increasingly unaffordable, home ownership has become a key issue in many societies. Hong Kong mirrors housing challenges faced by many large cities globally.

Home ownership is often considered an essential pillar of a stable life, along with career and marriage, and it is seen as a signal of one’s maturity, diligence and responsibility. The significance of home ownership among Hong Kong residents also stems from the traditional Chinese belief that places strong emphasis on family, land and housing.

Another widely accepted norm is that young people should purchase a flat before or at the time of marriage in Hong Kong, and that a substantial down payment and mortgage indicates one’s commitment to marriage.

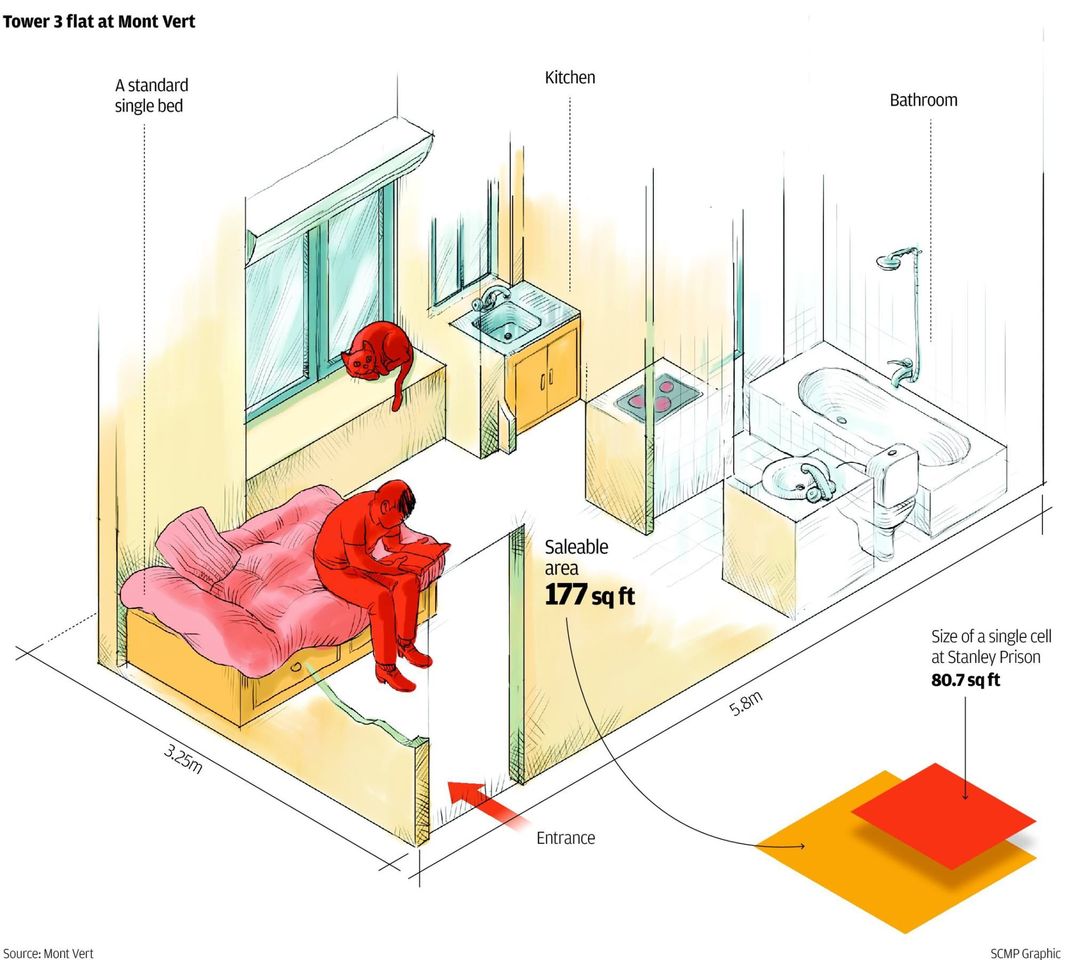

A graphic representation of a micro-flat at Mont Vert in Fanling, which

kicked off the trend of building tiny abodes smaller than 200 square

feet in size.

A graphic representation of a micro-flat at Mont Vert in Fanling, which

kicked off the trend of building tiny abodes smaller than 200 square

feet in size.

The desire for home ownership is further enhanced by the welfare system in Hong Kong. As the showcase of a laissez-faire economy, Hong Kong adopts development-oriented strategies and provides limited retirement protection and welfare benefits in general.

Hong Kong residents must rely on themselves for their own future. Buying a flat has become a crucial means of investing and saving up for retirement, particularly when real estate prices are rising and insufficient public housing is available.

Our study takes advantage of the lucky draw in the HOS as a semi-experiment. It shows clear evidence of the social benefits of home ownership and contributes to the policy debate with scientific support for future initiatives that aim to promote home ownership in Hong Kong and beyond.

The ancient Chinese sage Mencius once said, “One shall have his peace of mind when he possesses a piece of land.” It is time for Hong Kong to act now.