The time and money spent on each doctor in Hong Kong are massive, but that investment is still ill-conceived and pales compared to private sector incentives. The Hospital Authority should take some ideas from the private sector, such as letting doctors leave their contract only after repaying their training debts.

Steve Wynn once said, “Human resources isn’t a thing we do. It’s the thing that runs our business.” If a land developer sees their employees as vital as the organs of a company, it is an understatement to say the same for physicians in health care.

The time and money spent on each doctor in Hong Kong are massive. It costs the city HK$3.6 million (US$461,000) over six years to train one general practitioner. That is about the cost of one small apartment in Hong Kong, a city notorious for exorbitant property prices.

The bill the government foots for training a specialist for an additional six years is higher, though less well-documented. That is because specialist trainees learn as they work. Rather than a flat tuition fee, the cost comes indirectly in various forms: sponsorship for overseas training, consultant doctors’ time spent mentoring them and monetary and health costs incurred in mistakes requiring mediation or even medicolegal resolutions.

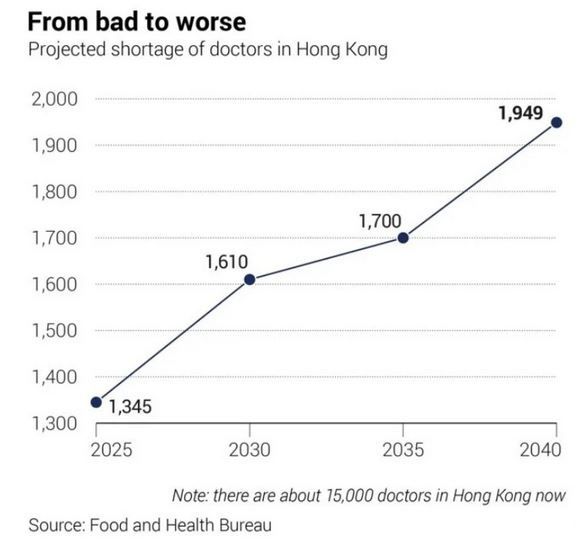

That the exodus of healthcare providers from the public sector has made headlines is hardly surprising. Against the backdrop of an ageing population,

Hongkongers are right to worry about tax budgets being squandered to no avail.

Hong Kong’s doctor-to-population ratio of two per 1,000 citizens is low compared Germany’s 4.5 or Singapore’s 2.5. Yet, the ratio has barely budged since University Grants Committee-funded medical training places increased by 60 per year. Where have our doctors gone?

In the Hospital Authority, the biggest stakeholder in health care in Hong Kong, the turnover rate of doctors rose from 4.1 per cent in 2020 to 8.2 per cent in 2022. If you look closer, the picture is more complex. In accident and emergency (A&E), radiology, ophthalmology, anaesthesiology and pathology, more than 10 per cent of fully trained specialists left public institutions compared to only 4 per cent in paediatrics and neurosurgery.

At the same time, “preventive health” is a notion gradually being hijacked by some opportunistic private health organisations to mean “test and thou shall live”.

Advertisements for health screening abound despite little evidence showing that doing a bundle of tests predetermined by a company helps. As the border reopens, a few organisations are aspiring to go public by leveraging the windfall of selling comprehensive screening packages to medical tourists from the mainland and beyond.

With little regulation, the market looks set to expand infinitely. More radiologists are needed to read scans just as more pathologists are hired to write biopsy reports. What can be done?

To ensure money does not go down the drain, we must first plug the sink. Reports concerning healthcare professionals emigrating to the United Kingdom or Singapore remain scarce because the Hospital Authority offers one of the highest salaries to physicians working in the public sector in the world, save for the United States where most healthcare institutions are privately run. Yet the outflow of doctors from the public sector needs to be stemmed.

Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu has promised to make efficient use of public resources. Key performance indicators, a measure inspired by private firms known for their efficiency, should be implemented.

The Hospital Authority has invested a massive amount of resources in physicians but the investment is ill-conceived. Besides conference leave – a sort of paid leave topping off annual leave – specialist trainees on a nine-year contract receive a gratuity bonus that is given out every three years, which has the effect of encouraging newly graduated specialists to stick around for just three years.

During those three years, many specialist graduates simply grab more sponsorships from the Hospital Authority to fund diplomas or get promoted as associate consultants to bargain for higher salaries in the private sector. The authority’s low-interest mortgage plan, for one, is dwarfed by the higher salaries offered by private institutions.

The authority can do more to balance the books. Calculating a fair “training price” would help. Professor Lo Chung-mau, the secretary for health, has floated the idea of binding doctors to the Hospital Authority for a longer service period. Borrowing the principle from private organisations is smart and essential.

In the private sector, resigning before the agreed date allows companies to charge the quitter a few months of salary on top of a “training fee” as a disincentive. This helps recover the company’s costs in recruiting and training new joiners.

The Hospital Authority could allow doctors to leave after repaying their training debts adjusted to inflation.

Whipping up passion among Hong Kong’s doctors might be meaningful in the long haul. But as an ageing population looms, the health of people will surely benefit from some human resources management.