A Lithuanian and his band of data scientists, business analysts, software engineers are toiling away in a nondescript corner of HKEX office in Central to prepare the exchange for the future of tech innovations.

On the eighth floor of one of Hong Kong’s most prestigious office towers, far from the madding street protests and coronavirus outbreak that imperilled the local economy, lies a hint of what the city’s future could be as a global financial centre.

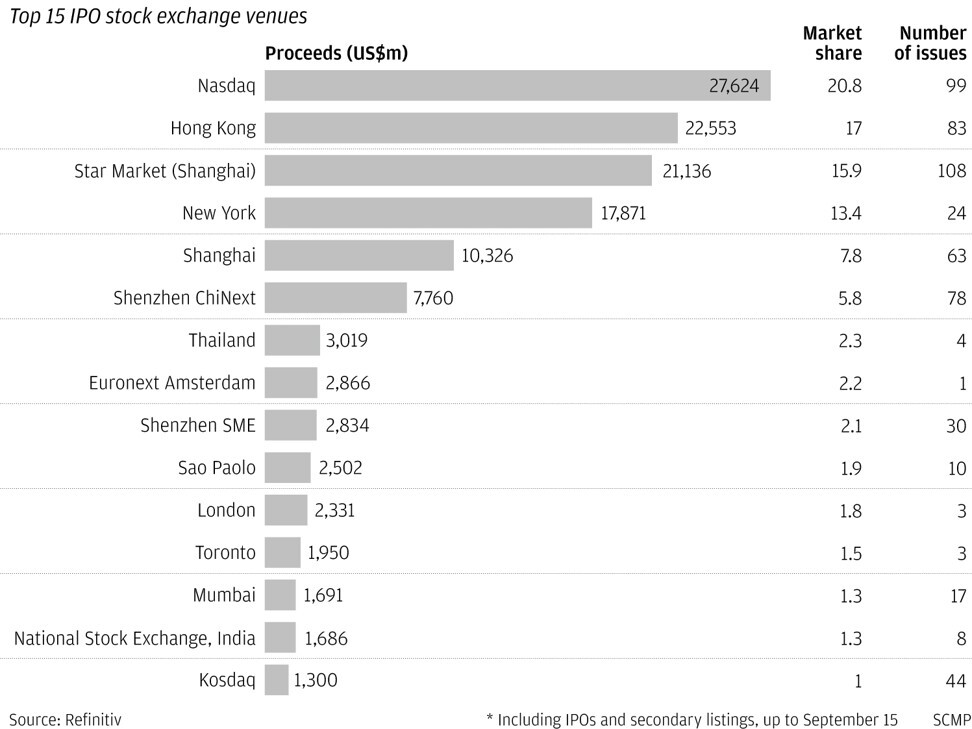

Here, Lukas Petrikas and a 20-strong team of data scientists, business analysts and software engineers are toiling away to imagine and redefine Asia’s financial hub, even as the Hong Kong stock exchange closes in on Nasdaq for the coveted 2020 crown as the world’s premier destination for initial public offerings (IPOs), the eighth time in 12 years.

The financial marketplace of the future could be one where the customer is the shareholder. It may be one where data from daily life can be scraped together, structured and traded.

Or it might just be a faster iteration of the current market of equities, bonds, currencies and commodities, augmented by data analytics and artificial intelligence that take the drudgery out of paperwork. Whatever it is, it’s up to Petrikas and his team at Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Limited (HKEX) to prepare Hong Kong for it.

“Hong Kong has always had an opportunistic streak throughout its history, pivoting quickly to capture the economic forces shaping the Asian continent, including trade, shipping, light manufacturing, real estate, aviation, and banking,” Petrikas, co-head of HKEX’s Innovation and Data Lab, said in an interview with South China Morning Post. “Today, Hong Kong is competing head-on with other cities for a share of the global digital economy, where geographical location may matter less than before.”

The lab, located in a nondescript corner of the HKEX office, grew out of the ambitious plan to reform the city’s capital market under the watch of Charles Li Xiaojia, the outgoing chief executive of the world’s third-largest publicly traded bourse operator.

The reform is the “moon shot” for Li, former chairman of the investment bank JPMorgan Chase in China before being hired in 2010 to lead HKEX.

During Li’s decade-long tenure, the HKEX opened a trans-border investment channel with the stock exchanges of Shanghai and Shenzhen, more than doubled its market value to HK$35 trillion (US$4.48 trillion), and in 2018 kicked off the biggest stock-listing reforms in three decades.

As Li prepares to step down in October 2021 at the conclusion of his three-year transformation plan, the HKEX will have to imagine its future as one of the four financial exchanges in the Greater Bay Area (GBA), a cluster of 11 cities in southern China including Hong Kong and Macau.

Hong Kong’s capital market abuts the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in China’s version of Silicon Valley, home to several of the country’s technology champions including the drone maker DJI, the 5G infrastructure giant Huawei Technology and Tencent Holdings, which topped Facebook in value in July.

Nearby in Macau, a former Portuguese colony that overtook Las Vegas a decade ago to become the world’s casino hub, a license was just granted to set up a Nasdaq-like market to help start-ups raise funds. Not to be outdone, the Guangdong provincial capital of Guangzhou will establish a marketplace to trade carbon emissions contracts.

That puts the pressure on Hong Kong’s stock exchange, where 80 per cent of its capitalisation and turnover are contributed by Chinese companies, to redefine its role to complement the various options coming up around it for raising capital.

The different exchanges “succeed in different ways,” Li said during a webinar last month with the Post. “We also partner with them. When we talk about the Stock Connect, it’s a three-[way] initiative” that involved Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzhen, he said.

The world’s financial marketplaces haven’t changed much ever since traders first gathered in 1611 at the Beurs van Hendrick de Keyser in Amsterdam to buy and sell shares of the Dutch East India Company. The word bourse, still in use today, is a corruption of “Beurs”.

Notwithstanding 21st century enhancements like low latency data feeds that power split-second algorithmic trading, paperless transactions or e-IPO in the age of the coronavirus pandemic, the essence of having a process to match buyers with sellers at the best price has not changed.

The search for that moon shot falls to Petrikas, born in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius, a city of Gothic and Renaissance architecture, and fewer than a million people.

He joined HKEX in 2012 after four years as a Rothschild associate in mergers and acquisitions, fresh out of university. He runs the lab with Xu Shen, former head of research and user experience within the finance division of China’s dominant search engine operator Baidu.

They are entrusted with modernising HKEX’s core systems to improve its efficiency. A big part of the lab’s role is to visualise a revolutionary future for Hong Kong’s equity market by infusing technology into its daily operations, Petrikas said.

That means probing for answers to the new role of stock exchanges and harnessing the relationship between listed companies and their stakeholders.

What if the fundamental relationship between companies and their shareholders can be changed, upended or democratised?

Can digital shares issued by entertainment companies be used as entry passes to the companies’ theme parks, cinemas, concerts or musical shows? Can sports apparel manufacturers raise capital by issuing shares to investors, and pay their shareholders dividends for using their clothing, footwear or other equipment during tournaments and races?

Other global exchanges, the providers of financial market infrastructure and data vendors are also gazing into the future in search for answers.

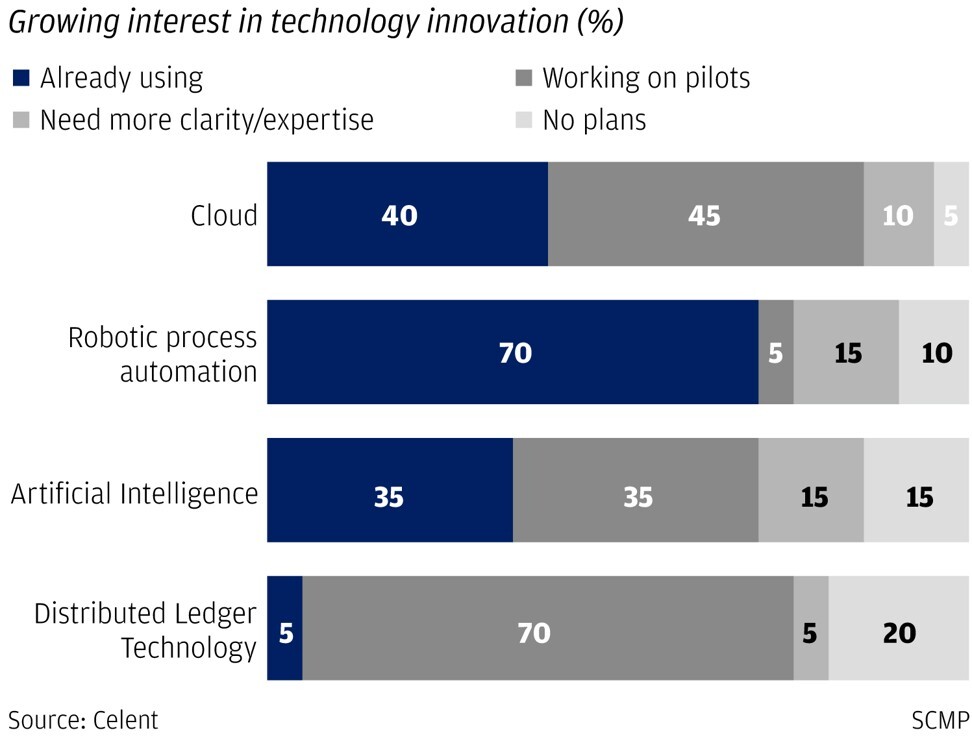

There is huge interest in using the latest and most innovative ideas such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence, machine learning and distributed ledger technology (DLT) to shorten time-to-market for new products and services.

The levels of adoption vary from 5 to 70 per cent, and large international groups are well ahead in the game, according to a Celent 2018 study commissioned by Nasdaq.

ICE, the owner of New York Stock Exchange, has developed a regulated ecosystem for digital assets such as bitcoin custody. It is launching a new consumer app and recently acquired a platform that supports roughly 4,500 loyalty, incentive and employee perk programmes across a broad range of industries.

This combination will make them an aggregator and a marketplace for a broader set of digital assets such as airline miles and loyalty points, its chairman Jeffrey C. Sprecher said in its annual report in March.

The answers for some of these questions may be many years away, if ever. For now, the search for the moon shot has translated into tweaks, changes and improvements that are immediately applicable to improve the HKEX’s efficiency.

By the end of this year, the lab would have automated 80 processes, including downloading and uploading files, composing emails and preparing reports. Another 60 have been earmarked for the bots in 2021. For HKEX’s size, to have these 140 processes done by bots “makes a huge impact,” Petrikas said.

“By the nature of its business, [HKEX] is never going to be on the bleeding edge of introducing crazy, wild, untested technology into the market,” he said. “Our role is to embrace it when it happens.”

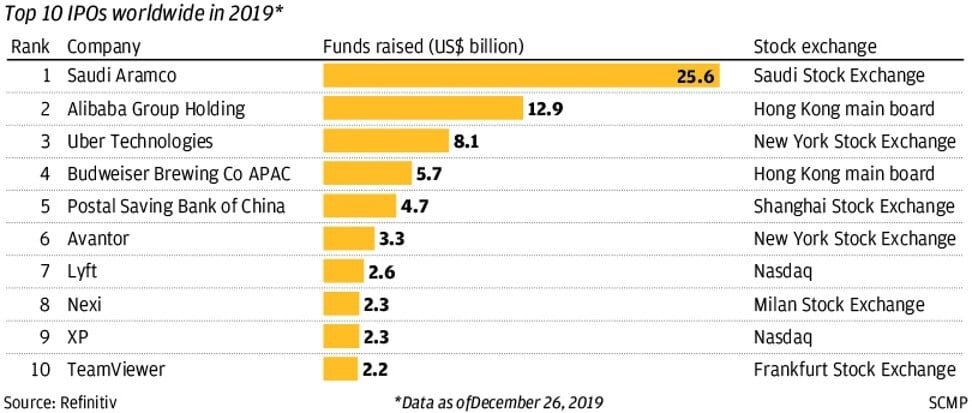

More exciting – if tougher – tasks lie ahead. A race is at hand with the Star Market in Shanghai, which gave the green light within four weeks for the Ant Group’s estimated US$30 billion dual listing, in what could become the largest IPO in world finance. A separate application, filed on the same day, is still wending its way through the HKEX’s listing committee.

Though yet to be announced, shortening the IPO processing time is high on the agenda, Petrikas said, which would enable billions of shares to move through the HKEX systems with more speed, efficiency and adaptability.

“We want to make sure that the technology catches up with that demand,” Petrikas said. “At the moment, it takes six working days for an IPO to go from pricing to trade, and the target timing can be T+1 or T+2, meaning one to two business days after pricing.”

“Every hour counts, because you are reducing market risks,” he said. “In a world where the market factors and politics and everything changes so quickly, by the time you price and then trade it, may be an entirely different world.”

The HKEX is actually at the forefront of global exchanges in its adoption of some technology, said Professor Allen Huang of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

The bourse is the first to attempt at applying DLT in cross-border trading, he said. HKEX has also deployed machine learning

and artificial intelligence to augment its market surveillance, using technology brought in from Nasdaq in 2018.

“It’s very difficult for outsiders to see [HKEX’s] work or progress as there’s not enough information,” said Huang, the associate dean at School of Business at the university, saying much of the innovations go under the radar. “The need for blockchain [in the Northbound scheme] is genuine, they do need it [to comply with the same-day trading requirement in China].”

Still, the most consequential changes in the annals of the HKEX, the ones that paved the way for its current prosperity, had been amendments to its regulatory regime, not quite technological.

The “Stock Connect” trans-border investment channels, first with Shanghai in 2014 followed by Shenzhen in 2016, came off of an idea scribbled on a paper napkin at a Shenzhen tea house by Li and Shanghai exchange’s chairman Gui Minjie.

Then came the most revolutionary market reforms in 2018, the joint decision with Hong Kong’s securities regulator to rewrite the listing rules to let technology start-ups with multiple classes of shares and pre-revenue drug producers raise capital. The result was three new chapters in the HKEX listing regime – biotech, weighted voting rights and secondary listings.

Since the listing overhaul, 99 new-economy companies and biotech firms have listed in Hong Kong, raising HK$390.5 billion. These companies account for 23 per cent of Hong Kong’s market capitalisation and 15 per cent of average daily turnover.

“Those changes are probably less than 5,000 words in listing rules, it‘s like a university dissertation,” Petrikas said. “But those 5,000 words have had an enormous impact. They have really changed Hong Kong.”

Li himself has suggested further tweaks to the HKEX listing rules to create another mega wave of IPOs in the city. Stockbrokers have suggested halving the current eligibility threshold to HK$20 billion for companies with weighted voting rights to list in Hong Kong.

Certainly, HKEX itself does not have the final say on this. The stakeholders involved in the process are not just investors and issuers, but also brokers, custodians, settlement banks and the Securities and Futures Commission.

“We will build on our foundation of being an adapter to connect mainland Chinese capital with international demand, continuing to advance and modernise our markets whether through new listings [or placing] a greater focus on environmental social governance goals,” Petrikas said. “HKEX is in a great position to sit everybody down and say, ‘let’s modernise this together’”.