Government must work to retain talent arriving from the mainland which is increasingly highly educated and well paid, researchers say.

New arrivals to Hong Kong from mainland China are increasingly well educated and highly paid, but many will choose to leave within five years in a damaging economic trend for the city, according to a new study.

Researchers from the Baptist University analysis published on Wednesday urged the Hong Kong government to stop the brain drain of skilled mainland arrivals, while social workers said many of the newcomers encountered discrimination and called on officials to do more to help them integrate in the community.

The research revealed a substantial increase in the socio-economic status of mainland migrants since 2001, and also found that Hong Kong’s population of under-20s would have shrunk by a quarter without the past two decades of inbound flow from over the border.

“It is a problem when many of these highly educated people do not stay long in Hong Kong,” said Professor Cheng Yuk-shing, who led the research.

Commissioned by the new migrants’ rights group, Society for Community Organisation, the research found it was no longer the case that mainland residents settling in Hong Kong were unskilled and reliant on public support when they arrived.

In 2001, some 70.4 per cent of the city’s mainland migrants were only educated to junior secondary level at most. The figure fell to 52.2 per cent in 2016, according to the research.

The proportion of those who pursued tertiary education rose from 5.7 per cent to 19.5 per cent over that period.

From 2001’s 1.1 per cent, some 8.5 per cent held a master’s degree in 2016, which compares favourably with the 4.9 per cent for the overall Hong Kong population.

During the 15-year period, the incomes of mainland migrants increased 70.8 per cent, with their household incomes rising 45.1 per cent. That compares with 55 per cent and 33.7 per cent respectively for the Hong Kong population as a whole.

Further analysis of labour participation rates between male new migrants and locals of the same sex showed that in 2001, the rate for the migrants was 11.9 percentage points lower. It narrowed to zero in 2016.

In 2014, some 28,000 new migrant families were living under the poverty line, accounting for about five per cent of the city’s total households living under the poverty line. The figure fell to 24,000 in 2019, or 3.7 per cent of the total.

This was despite a rise in the number of Hong Kong households living below the breadline, from 555,000 to 649,000.

The researchers also looked at families receiving comprehensive social security assistance in 2019 and found that only around 3.4 per cent involved new migrants from the mainland, down from 4.1 per cent in 2014.

Professor Cheng led the study on mainland residents moving to Hong Kong.

Professor Cheng led the study on mainland residents moving to Hong Kong.

Professor Cheng said the findings debunked many misconceptions about mainland migrants.

“The fact is there have been significant changes in the characteristics of mainland migrants in recent years, where both their incomes and education attainments have substantially increased,” Cheng said.

But his research showed many of the educated migrants did not stay in Hong Kong for very long.

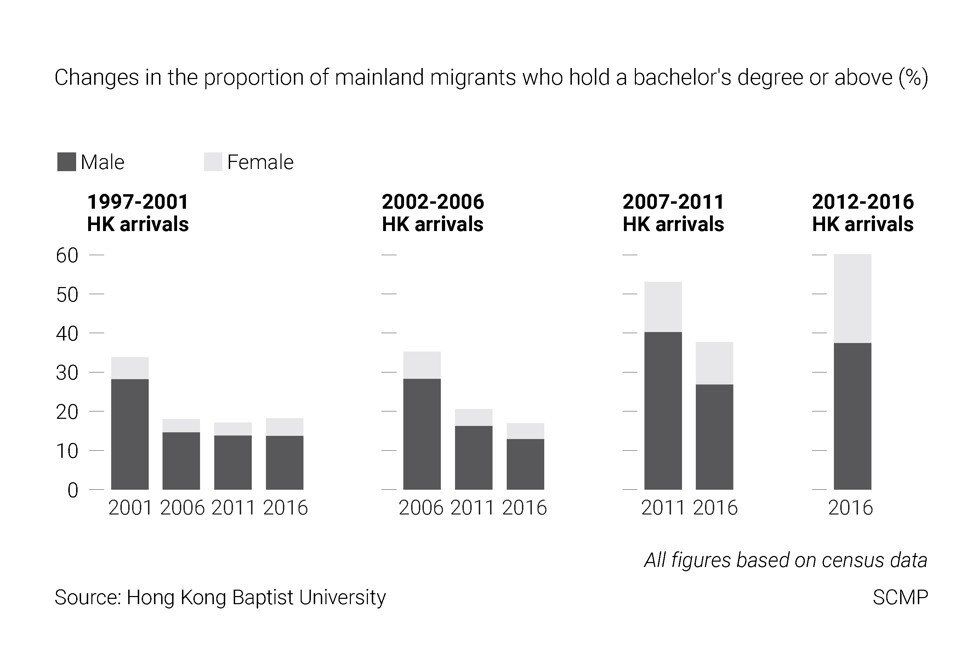

Among those male migrants who arrived from 1997 to 2001, 28.2 per cent held a bachelor’s or more advanced degree in 2001. This percentage almost halved, to 14.6 per cent in five years, and continued to fall in later years. “Immigrants from other periods show similar trends,” the report said.

“The government should come up with a strategy to retain such talent as these people can contribute greatly to the Hong Kong economy,” Cheng added.

Sze Lai-shan, deputy director of the society, said she hoped people’s misperceptions about mainland migrants would change.

“Some people still consider immigrants as a burden on society ... ‘they came here for welfare and they are poorly educated’,” she said. “But according to the survey, we find that actually is not true.”

Sze added many new migrants, educated or not, faced discrimination in Hong Kong.

“It is hard even for some educated immigrants to find jobs in Hong Kong that suit their level of qualifications because their English is not as good or up to par. So, when they’re rejected, many return to China to find jobs that suit them.

“When mainland immigrants fail to assimilate, it is a lose-lose situation,” she said, “The immigrants are unhappy, Hongkongers are unhappy.”

“Unlike some overseas countries, when mainland immigrants arrive, there is no course they can take or anything to tell them what they should do to assimilate with the community, so the government should consider taking up such programmes,” Sze said.

Migrants with lower levels of education also reported being subjected to forms of discrimination, despite their contributions to Hong Kong.

School janitor Mandy Dai, 56, worked as a street cleaner when she came to the city from Guangdong province in 2010.

“Once they hear your accent they’d yell at you to go back to mainland China, such as when we’re just shopping at the wet market,” she said. “There’s a lot of psychological pressure.”

Another migrant Cheung Ling, 55, has worked mainly as a domestic helper since coming to Hong Kong in 2003. But she is juggling two part-time jobs at the moment after losing a full-time one during the pandemic.

“I think I have already done my best and played my part in contributing to Hong Kong,” she said.

Most mainlanders arrive in Hong Kong under the “one-way permit” scheme. Created in the 1980s to enable orderly family reunification, the programme allows up to 150 mainland residents each day to move to Hong Kong. But mainland authorities administer the scheme and Hong Kong has no say in who is admitted.

In 1997, some 50,300 mainlanders moved to Hong Kong via the scheme. The figure peaked at 57,500 in 2000 and then steadily fell, to 42,600 in 2010 and then to 39,100 in 2019.

Debate regarding new migrants and the pressure on the city’s public services heated up in 2019 after some local doctors said a large portion of their patients were new arrivals, who they pointed to as the source of overcrowding problems in hospitals.