RTHK’s ‘worrying’ move to follow Beijing’s lead in banning BBC programmes threatens the ‘free flow of information’ on which Hong Kong has thrived, one advocate says.

A move by Hong Kong’s public broadcaster to pull the plug on programming from Britain’s BBC following a ban by Chinese regulators has sparked alarm in the city as analysts warned of a shrinking space for press freedom.

The decision by RTHK to stop broadcasting BBC’s World Service and News Weekly starting from 11pm Friday night also prompted concerns that private TV operators could be pressured to follow suit. At least one network, however, told the Post it would continue to offer BBC programming for now.

In the early hours of Friday, RTHK announced it would no longer relay the BBC programmes, shortly after China’s National Radio and Television Administration banned the British public broadcaster “within Chinese territory”, citing its failure to meet broadcasting requirements.

The BBC had recently broadcast stories critical of Beijing on the coronavirus pandemic and internment camps for ethnic Uygurs and other Muslims in its far western Xinjiang region. China had rejected those claims and described the facilities as “vocational training centres” helping to stamp out extremism and give people new skills.

Beijing said BBC reports had damaged China’s interests and ethnic unity. But the ban came after Britain revoked the broadcasting licence of China Global Television Network (CGTN) last week, after it said the state-owned Chinese channel was ultimately controlled by the Chinese Communist Party and therefore violated British laws.

RTHK had previously aired BBC World Service daily from 11pm until 7am, and the Cantonese-language radio show BBC News Weekly every Sunday at 7am.

“When the central government takes a stand, and the Hong Kong government follows suit, RTHK [as a public broadcaster] would not be able to escape from that,” said Grace Leung Lai-kuen, a lecturer at Chinese University’s school of journalism and communication.

Leung also believed the local government had been tightening its grip on the public broadcaster in recent months, citing incidents of authorities slamming its performance over seven substantiated complaints in two years.

BBC reports on Chinese internment camps in the western region of Xinjiang had drawn Beijing’s ire.

BBC reports on Chinese internment camps in the western region of Xinjiang had drawn Beijing’s ire.

The public broadcaster has been put under close scrutiny by officials and pro-establishment figures, especially after the 2019 social unrest, as it had been accused of siding with protesters against the government and the police force.

“Without many other choices, RTHK has to move as a team with the government, and keep up with the pace,” Leung said.

Bruce Lui Ping-kuen, a senior lecturer at Baptist University’s journalism department, said he was not particularly surprised by RTHK’s unprecedented move, but added that it reflected shrinking freedoms in Hong Kong over mainland China’s decisions.

Bruce Lui (yellow vest) observes a public gathering in Causeway Bay last year.

Bruce Lui (yellow vest) observes a public gathering in Causeway Bay last year.

“This incident has reflected that – in terms of issues related to the media sector – there is no longer much space for ‘two systems’ to exist, rather just ‘one country’,” he said, referring to the one country, two systems governing arrangement under which China rules Hong Kong.

“[Compared with] before, even when Beijing targeted certain individuals or media organisations, there was still space [for them] in the city. Hong Kong can no longer be a ‘safe haven’ and be granted exemptions under the ‘one country’ umbrella.”

Lui added that he believed other private TV operators in Hong Kong relaying BBC World Service might be scrambling to find out whether they would legally need to follow RTHK’s move, given that Beijing’s ban was imposed “within Chinese territory”.

On Friday, the BBC said it condemned a decision by the Chinese authorities to take its World Service off air in Hong Kong, adding access to accurate and impartial news was a fundamental human right.

The broadcaster said it would make every effort to continue making its news available to people.

“We stand by our journalism and totally reject accusations of inaccuracy and ideological bias,” it said in a statement. “Our journalists have reported stories in mainland China and Hong Kong truthfully and fairly, as they do everywhere in the world.”

Hong Kong Journalists Association chairman Chris Yeung Kin-hing called RTHK’s decision “disturbing and worrying”.

“BBC World Service was banned on the mainland because of alleged content violations. RTHK and the relevant policy bureau should explain whether their ban was made on the same ground. And if yes, will the same rule be applied to all other foreign media?” Yeung asked.

“Hong Kong thrives on diversity and openness and free flow of information … The RTHK ban has given rise to concerns that foreign media programmes currently broadcast by privately run broadcasters may face a similar ban in the future.”

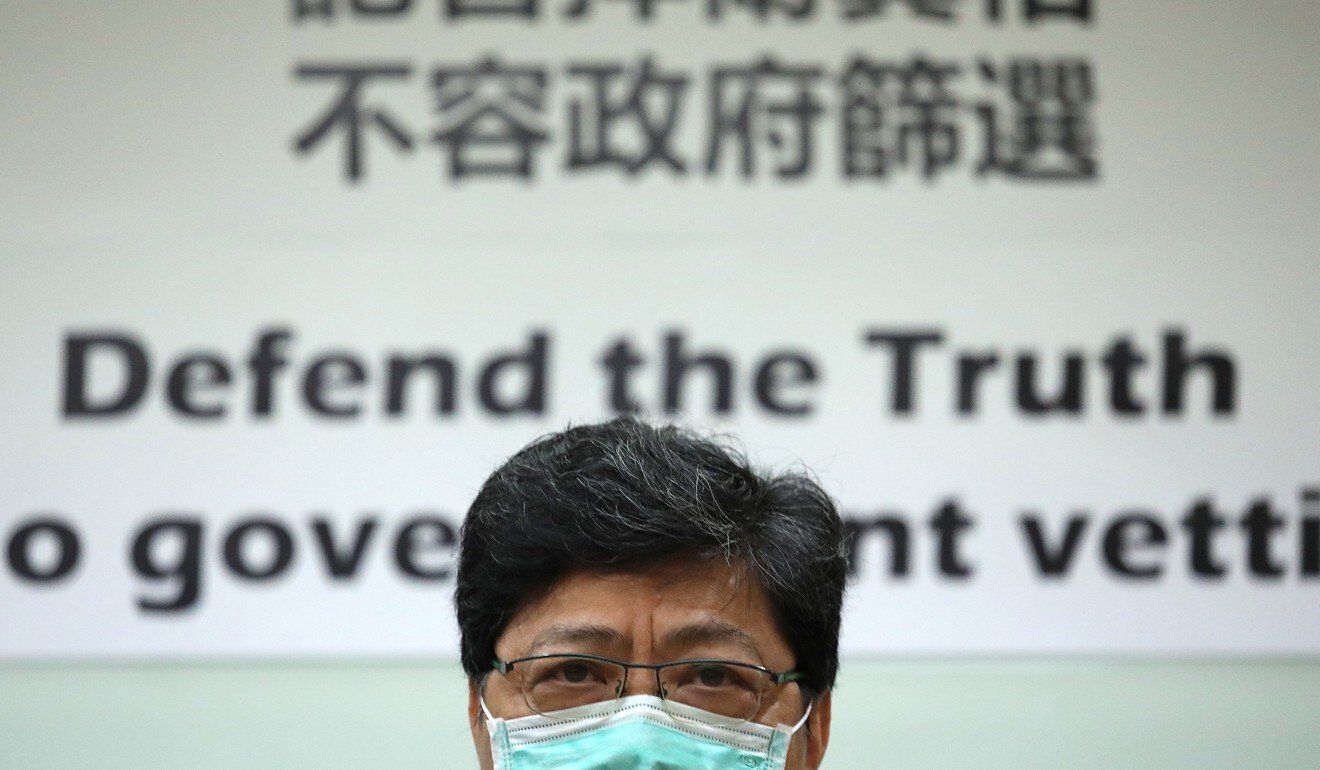

Chris Yeung, chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association.

Chris Yeung, chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association.

In a written statement, RTHK cited Beijing’s decision as the reason for its move, while a spokeswoman told the Post the decision was made within the broadcaster’s management.

“The decision was made among RTHK management, and concerned heads of sections were informed this morning,” said Echo Wai Pui-man, head of corporate communications and standards at RTHK.

Starting from Friday, RTHK Radio 3 and 4 will air the same as-yet unspecified programme from 11pm to 7am to replace the World Service. RTHK Radio 1 and 2, meanwhile, will both also broadcast the same unspecified programming between 7 and 8am on Sundays to replace News Weekly. New programmes will be launched on Radio 1 and 4 at a later date, the spokeswoman added.

RTHK Programme Staff Union chairwoman Gladys Chiu Sin-yan said the move was “very regrettable”, and questioned if the ban ran contrary to the broadcaster’s mission of providing diverse and popular programmes.

“Under ‘one country, two systems’, it is unprecedented for a decision by China’s National Radio and Television Administration to affect Hong Kong media,” she said.

“If RTHK and the government believe BBC World Service’s reports are unfounded from a professional viewpoint, then they need to give a clear explanation with evidence that supports those claims.”

The EU also weighed in the matter on Friday, calling in a statement for China’s ban on the BBC to be reversed, and blaming RTHK’s decision to follow suit for “further adding to the erosion of the rights and freedoms that is ongoing in the territory, following the imposition of the National Security Law in June 2020”.

“This also illustrates the reduction of Hong Kong’s autonomy within the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ principle,” the statement adds.

But lawmaker Ben Chan Han-pan, a member of the pro-establishment Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, as well as the legislature’s IT and broadcasting panel, said he believed RTHK’s decision had little to do with one country, two systems.

“I support RTHK if they want to set things straight. I respect their decision to do the right thing,” he said. “Plus, BBC’s productions are also available online … If people want to listen to [or watch] BBC, they can do that on the internet.”

“BBC’s programmes are, after all, reflecting Britain’s perspectives,” he added. “After so many years following Hong Kong’s return to [China], why must [RTHK relay] programmes from BBC?”

The Commerce and Economic Development Bureau, which oversees the public broadcaster, said it respected RTHK’s decision to pull the plug on BBC broadcasts. But the bureau did not respond to questions on whether the government planned to ban BBC programmes from airing or block its website in Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, without naming the BBC, a spokeswoman from the Office of the Communications Authority added that it was up to RTHK, or any other local operator, whether to relay programmes from “a particular foreign channel”. The authority, she added, “did not set any boundaries”.

A check by the Post found the city’s private broadcasters, Television Broadcasts (TVB), Cable TV and Now TV, provide paid relaying for the BBC World Service. The channel was also still listed on Hong Kong’s Communications Authority’s list of licensed broadcasting services as of Friday under “domestic pay TV programme services”.

Other BBC programming, such as BBC Earth and BBC Lifestyle, is also available through local broadcasters’ services.

Now TV said on Friday that it would still offer BBC content as usual, and would notify customers as soon as possible if there were any changes. A TVB spokeswoman said they were observing the latest developments, while a Cable TV spokeswoman declined to comment on the matter.