The changes will align Hong Kong laws with those in Australia, Britain, Canada and Singapore, experts say.

Last year, office worker Bobo* was on the escalator at an MTR station after work, when she suddenly felt her dress move. She was shocked to find a man behind her was taking a photo of under her dress. She felt angry but was also afraid he might harm her if she said anything.

Bobo, who is in her 20s, decided to confront him. Noticing the commotion, people nearby came to her aid, stopped the man from fleeing and called police.

“I was confused and afraid, but I also wanted to do something … because if I just stood there and did nothing, I would be so angry with myself,” she says.

Police were on the scene in 15 minutes and the man was arrested. He was eventually charged with outraging public decency, because Hong Kong currently has no specific law against taking pictures up women’s skirts, known as upskirting.

That is set to change with the introduction of a proposed amendment to the Crimes Ordinance, aimed at preventing six new offences in the city. They include: voyeurism, defined as observing or recording the intimate acts of others; non-consensual recording of the intimate parts of a person for a sexual purpose or dishonest gain, which includes upskirting and taking photographs down a person’s top; non-consensual publication of intimate images; as well as the threat to publish intimate images or videos without consent. They each will carry maximum jail terms of five years.

The amendment is expected to cover offences committed in both public and private spaces. Offenders convicted of the first two offences would go on the sex offenders’ register.

On Thursday, the government introduced the Crimes (Amendment) Bill 2021 into the Legislative Council for the first and second reading.

Advocates, lawmakers and legal experts welcomed the move, saying it was an essential step to plug a gap in the law. They added the addition of the offences would align Hong Kong laws with those in countries such as Australia, Britain, Canada and Singapore.

However, they said the proposed bill did not go far enough and was missing key parts, such as covering altered images, or “deep fakes”, where artificial intelligence is used to make images appear pornographic. With the rise in technology, experts said, this would become more of a problem in future.

“If it is written in black and white that it is illegal for someone to take or be caught taking intimate photos of your body parts, it sends a clear message to the victims that what they are experiencing is a criminal act and they have the possibility to ask for the judicial system to intervene when such abuse takes place,” says Jacey Kan, an advocacy officer for the Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women.

In the past, culprits accused of committing the above offences were prosecuted for “loitering”, “disorder in public places”, “outraging public decency” and “access to a computer with criminal or dishonest intent”.

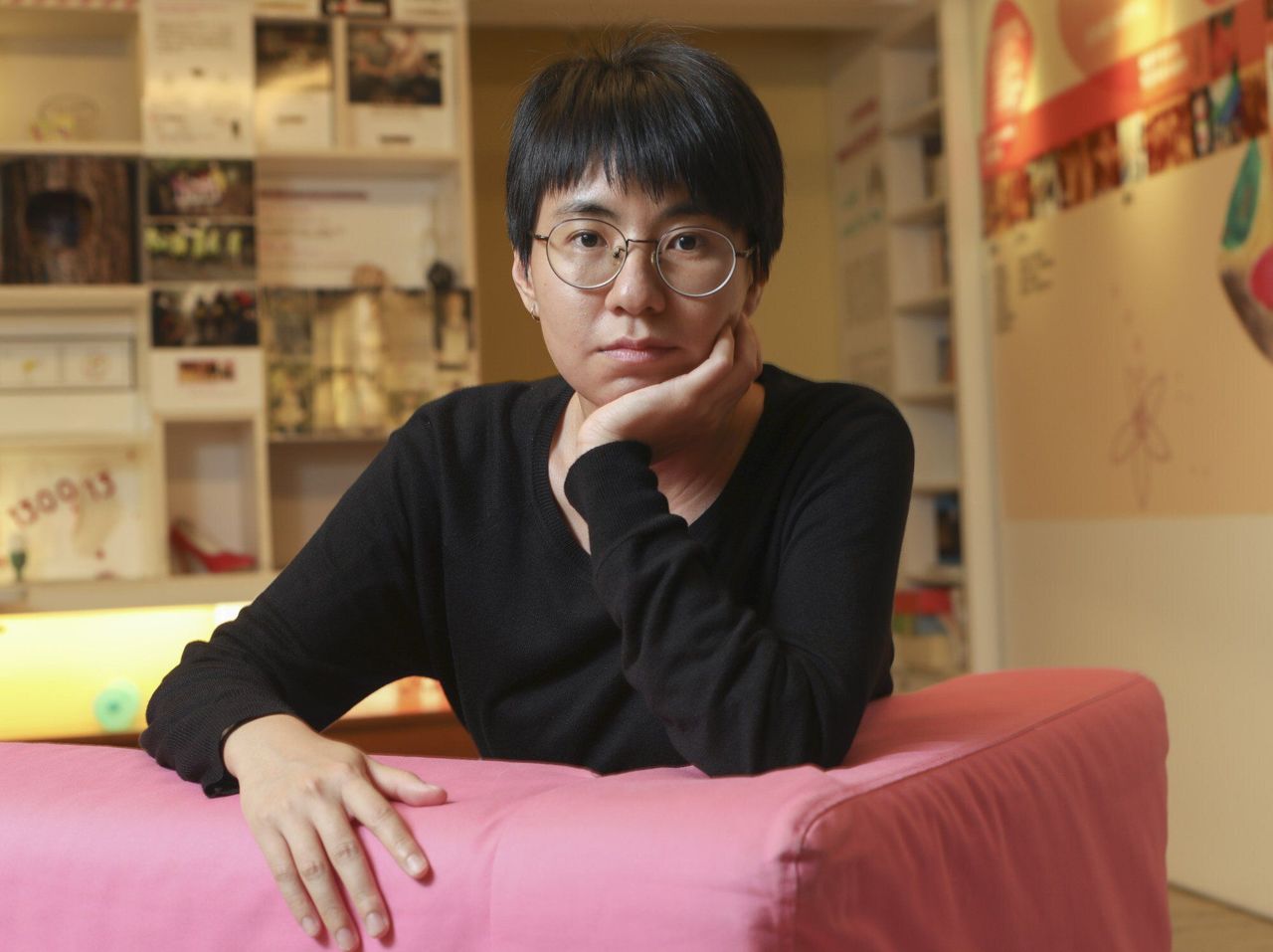

Jacey Kan, advocacy officer for the Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women.

Jacey Kan, advocacy officer for the Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women.

Former director of public prosecutions Grenville Cross SC says the offences only cover acts in a public place, and not those having occurred in a private setting.

The Court of Final Appeal ruled in April 2019 that the offence of “access to a computer for criminal or dishonest gain” does not apply when a person only uses their own device, rather than one belonging to someone else, restricting how prosecutors use the charge.

“The weaknesses in the criminal law have created problems for law enforcers for many years,” Cross says, adding the reforms are “long overdue”.

Bobo’s case went to trial. With no witnesses or surveillance camera footage of the incident, and police unable to unlock the man’s phone so the photo could be used as evidence, her oral testimony was the sole evidence.

The man was found not guilty, due to insufficient evidence.

It took Bobo a month to accept the verdict. She hopes the new law will improve the situation for other victims.

Last year, out of 363 reported cases involving clandestine taking of indecent photos in public places, 281 arrests were made over offences including loitering, disorder in a public place and outraging public decency. In 2019, there were 263 arrests out of 321 cases.

However, legal reform advocates believe upskirting happens much more frequently than reported, partly because victims are often not aware they have been photographed. They say the local rail network is the most common place for such incidents to take place.

Plugging the loopholes

The existing laws often fail to protect victims of revenge porn, or image-based sexual abuse, most of whom are women in their early 20s, according to the Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women, which says the crimes also affect members of the LGBT community.

The association has noticed an increase in image-based sexual abuse, receiving 133 cases in 2020, compared to 44 in 2019.

A five-month relationship wrought lasting damage to 25-year-old retail worker Claudia*. She says her boyfriend at the time took photos of her in her undergarments, as well as of her genitals, when she was sleeping, without her knowledge or consent.

After the couple broke up, the photos were uploaded to an anonymous social media account on Instagram and Facebook. The photos were also sent to her family, friends and colleagues, along with messages saying she was a sex worker. He would also turn up outside her office.

Claudia was devastated. At work, she says, her colleagues discussed the photos.

Facebook and Instagram have rules against nudity and the posts were removed, but Claudia says new accounts appeared, with some using names similar to hers. She believes people took screenshots of the images, and has no idea how many photos still exist.

Claudia says her ex-boyfriend denied he was behind all this. She approached the sexual violence crisis centre Rainlily and reported the incident to police two years ago. But no charges have yet been brought against her former partner.

She developed suicidal thoughts. She spent a lot of time at home and was afraid to meet new people, worrying they might have seen the images. She says the trauma of having such intimate photos exposed to the world continues to affect her life.

“The photos are out there and I don’t know how many people have seen them,” she says. “I was so stressed and crying all the time, because I was feeling so helpless. The situation was out of my control.”

Image-based sexual abuse refers to all forms of non-consensual taking and sharing of intimate images, including altered images, and the threats to share images, according to Clare McGlynn QC, a law professor at Durham University in Britain, who coined the term in 2016.

According to a survey released by the Association Concerning Sexual Violence Against Women last year, 73 per cent of participants said they had been photographed or filmed nude or in a sexually revealing way without their consent, with more than half revealing the perpetrators were people they knew.

The concern group received 206 responses to a multiple-choice questionnaire posted online that listed different types of image-based abuse, with 90 per cent of the participants being women. Respondents were aged 11 to 54.

The Equal Opportunities Commission says image-based sexual abuse causes humiliation, intimidation and distress to a victim, and often adversely affects their mental and physical health.

“In my experience of image-based violence, victims often blame themselves, because they have chosen to believe the persons and sometimes even sent out some of their naked pictures or agreed to take some of the pictures or films,” case counsellor Rebecca Lam says.

The proposed new offences include the threat to publish intimate images, where consent might initially be given for the taking of such images, but not for their publication.

Peter Reading, a senior legal counsel at the Equal Opportunities Commission.

Peter Reading, a senior legal counsel at the Equal Opportunities Commission.

Experts say the expansion of electronic communications has made it easier to take photos clandestinely and distribute images anonymously.

“Many people are using chat groups and social media to distribute these sorts of images for various reasons, whether it’s for profit or sexual purposes. These days, people can often post things anonymously, which is another reason why this seems to be increasing,” says Peter Reading, a senior legal counsel at the Equal Opportunities Commission.

Experts say some victims could be left out, as the law on the distribution of intimate images will only apply in a case where the intent is to cause humiliation, alarm or distress, and the law on upskirting will only apply if the perpetrator has a sexual motivation or does it for financial gain.

An expert on laws relating to online abuse and pornography, McGlynn says the law fails to cover all possible causes behind abuse, noting that the motivations behind taking and sharing intimate images are varied.

Referring to the system in England and Wales, which require proof of particular motives from perpetrators, she says the law is difficult to enforce.

Pro-establishment legislator Elizabeth Quat agrees: “It is not rare for distributors to share images with others because they merely want to flaunt. If that is the case, the government cannot prosecute those people.”

Still, Quat says the amendments are necessary to close the “legal vacuum” and there is an urgency to get the bill out to better protect victims such as Bobo.

It took Bobo more than six months to return to the MTR station where the upskirting incident occurred, as she did not want to be reminded of what happened to her. She never wore the dress again. Now, she wears long dresses and trousers.

“I am angry to be honest because maybe he does not remember my face, but what he did at that moment really affected my life,” she says.

“And it has changed how I dress.”