The termination of the agreement to build Melaka Gateway could mean the end for the US$10.5 billion development.

The government of the Malaysian state of Melaka has terminated an agreement with the main developer of a Belt and Road Initiative

infrastructure project after years of delays, raising questions about its future and the Malaysian government’s commitment to other projects under the strategy.

The Melaka Chief Minister’s Office said in a statement that the agreement with KAJ Development on the Melaka Gateway mixed development had been ended after the developer failed to complete the 246.45-hectare maritime initiative, which it signed on to in October 2017 and was meant to include port facilities, economic parks and tourist attractions on three artificially constructed islands.

“The company is also required to return the project site, effective upon the termination notice issued by the state government,” said the statement on the 43 billion ringgit (US$10.5 billion) project, which saw KAJ Development working with three Chinese companies, including state-owned Chinese energy firm PowerChina – the main financial backer.

Originally proposed in 2014, the project had long been seen as a white elephant, particularly because it included the building of yet another port in a nation already well served by existing facilities. There was little sign that any work on the project had been completed, amid rumours that the Chinese investors had pulled out.

Even now, say observers, it remains unclear if the project can or will continue.

“The project was very ambitious and not very well grounded in an economic or political sense,” said Francis Hutchinson, senior fellow and coordinator of the Regional Economic Studies Programme at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

“Economically, due to its location and the current overcapacity in the port sector, it was not very feasible. Politically, it did not check the boxes as it would have competed with existing facilities owned and run by corporations, and it did not have buy-in from large conglomerates or government-linked companies.”

“The main local player pushing the project was KAJ Development, which is not an established name at the national level. It had some buy-in from the Melaka state government through one of its subsidiaries, but this is not enough in the Malaysian context to get things going.”

Melaka Gateway was marketed with a strong historical dimension because of the state’s legacy as an important sea route. It was also launched at the same time the belt and road strategy was kicking off, which made the project appealing for Chinese state-owned enterprises seeking potentially profitable investments.

“However, after a time, it became clear that did not make economic or political sense,” said Hutchinson, adding that with the proposed benefits of the project mostly going to the state, federal support was unlikely.

“The Najib Razak administration classified it as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, but never included it in planning documents such as the 11th Malaysia Plan or National Physical Plan,” he said, referring to the former prime minister who was in power from 2009 to 2018. “It also never invested any resources in the initiative.”

Hutchinson added that the government that followed Najib’s – Mahathir Mohamad’s Pakatan Harapan coalition – “was openly against the initiative”, with Mahathir stating that “it was not necessary”.

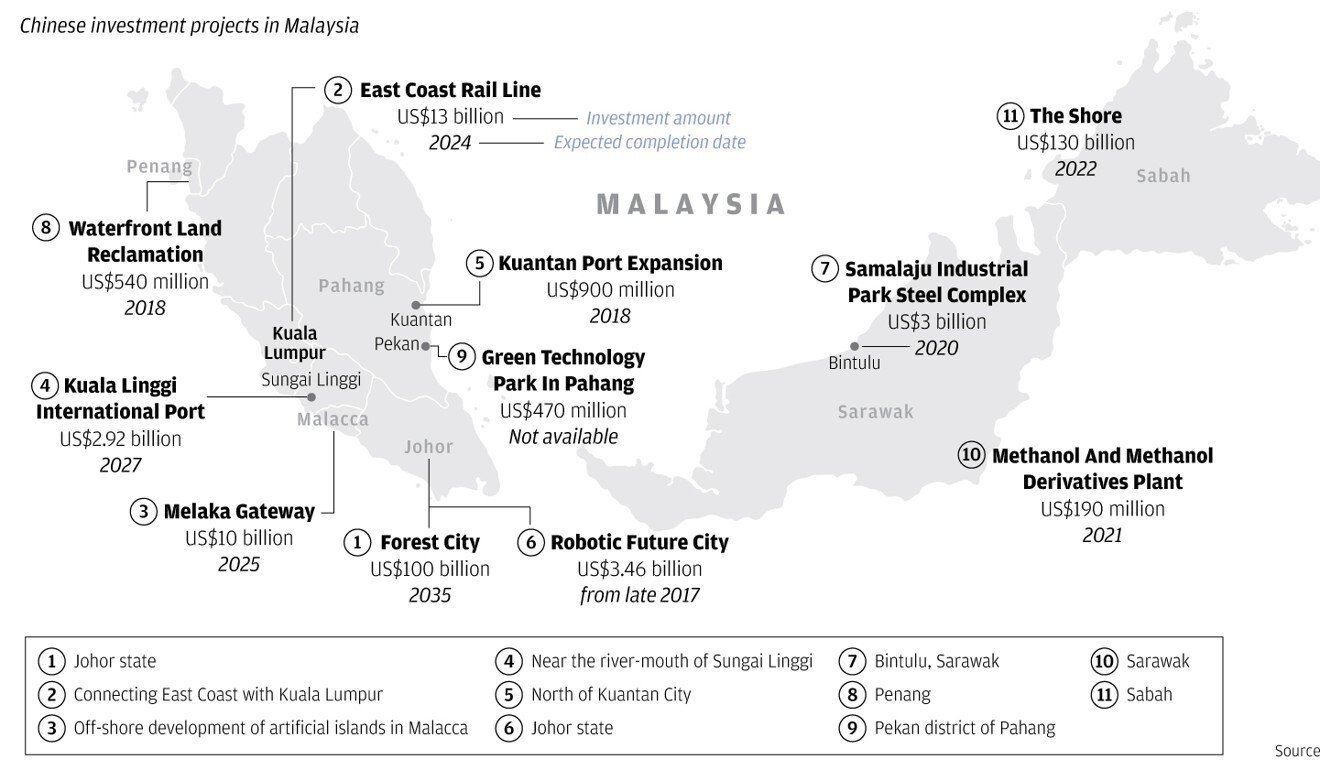

Malaysia has positioned itself as a key nation in China’s Belt and Road Intiative, and was the first to confirm attendance at China’s second belt and road summit last year. It has a host of projects under way, including the widely anticipated East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), a multibillion-ringgit China-backed railway project that will connect rural states along the east coast of the nation’s peninsula.

Recent political movements in Malaysia have made the future of the Gateway even messier, said political economist Terence Gomez.

“The current administration is focused on political survival and battling the coronavirus pandemic. When Pakatan Harapan fell and was replaced by Perikatan Nasional, the project returned to limbo because nobody was paying much attention,” Gomez said.

“The latest news indicates that the project is brought to a close, which is interesting as now we need [foreign direct investment], the Chinese economy has revived and is registering growth. Given this, why are they not choosing to move ahead with the project?”

The Melaka Gatewayis not the first belt and road project to be delayed or cancelled. In 2018, when the Pakatan Harapan coalition came to power, it set about cancelling two natural gas pipeline projects worth US$2.3 billion, citing high costs. It also delayed other projects, including the ECRL.

The Pakatan Harapan administration, which fell in March 2020 in a political coup, had renegotiated several China-backed projects to adjust costs, citing empty government coffers drained by the administration of Najib, who was recently found guilty of several charges of corruption and abuse of power.

“The project has been in trouble for a while already but I doubt it will have significant impact in the sense of belt and road cooperation,” said China expert Ngeow Chow Bing of the University of Malaya, adding that projects like the ECRL were still more important to China-Malaysia cooperation.

“I think the problems related to this project is well understood by both sides to be unrelated to Malaysia’s foreign policy stand. It is just a failed project,” Ngeow said. “I think the domestic perception perhaps will be affected, but only in a limited way. From the very beginning the project was too ambitious and unrealistic. Unfortunately it could not deliver.”