Daughter of a man executed for murder is found liable by a Chinese court for his debts, and when the nine-year-old cannot pay, she is sanctioned under social credit system. After an outcry, the court reverses its decision.

A Chinese court’s decision to punish a nine-year-old girl for failing to repay her dead father’s debts has triggered heated debate about the growing reach and power of the country’s judicial system.

The punishment also prompted concerns about the country’s burgeoning social credit system.

The social credit system is similar to a credit-scoring system. It punishes individuals and businesses that fail to follow rules and regulations and rewards those who perform actions deemed beneficial to society, based on a wide range of data it collects.

In 2019, a court in China’s Henan province ruled the young girl, Chen Man, was liable for her father’s debts. The debt centred around a financial dispute with a man named Wang who had bought a flat from the girl’s father for about US$84,000.

Wang never received the legal rights to the flat before Man’s father was sentenced death in 2013 for killing the girl’s mother and grandmother the previous year.

Wang sued the girl to get his money back because the father was dead. The court ruled in Wang’s favour and demanded that Man pay off her father’s debt. Man was unable to repay the debt. She had been unaware of the lawsuit because her grandfather dealt with the case.

In November, after failing to comply, the court put her on a restricted spending list, prohibiting her from “high-level consumption” activities that include flying, travelling by high-speed train and checking into hotels. A ban such as this is often used in China to force a debtor to pay up.

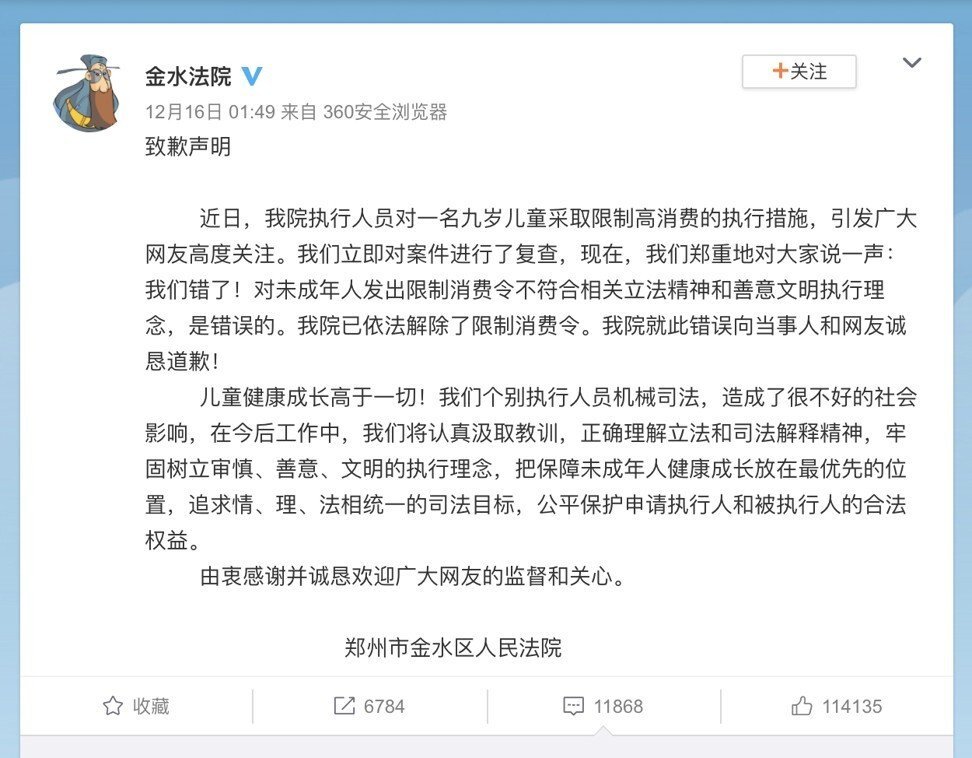

However, an investigation by the Chinese newspaper Southern Weekend highlighted the young girl’s plight and led to the court revoking its decision. Two days after publication, the court apologised online, saying: “We are sorry! Putting children on spending restriction orders goes against the spirit of the related legislature.”

The publicity about the case led to widespread criticism of the court’s decision and provoked heated debate across the country.

“Thanks to media exposure, the court reversed its decision,” said David Zhou, a criminal defence lawyer based in Beijing. The report coupled with the girl’s tragic family history had put immense pressure on the Henan court, he added.

As China speeds up the building of a comprehensive social credit system, which can punish citizens deemed “untrustworthy” by a court, Man’s case reflects the power the courts have over Chinese people.

“The change of the ruling showed that the judges didn’t look thoroughly into [Man’s] case and her ability to pay back debt before punishing her,” said Zhou.

“A Chinese court can decide by itself, without the presence of the defendant or their lawyer, whether to issue a spending restriction order. This puts the defendant in a vulnerable place,” he added.

According to the law, judges need to consider factors including the defendant’s attitude to paying off the debt, their financial situation and past financial records before issuing a spending restriction order.

Once someone is handed a spending restriction order they are barred from six main activities, including booking a flight or a high-speed train ticket, enrolling offspring in private schools and renovating homes. The order is one of the punitive measures introduced by China’s social credit system.

While checking a person’s credit rating for the issuing of bank loans is not new in the West, China’s state-controlled social credit system is unique in its wide reach.

Apart from a person’s financial behaviour, the system also judges people’s social behaviour, such as whether they jaywalk, drink-drive or dodge subway fares.

Good social credit scores bring people rewards, such as the waiving of deposits for public housing rentals, while negative scores lead to punishment such as that faced by Man.

Then Chinese premier Wen Jiabao formally introduced the idea of building a national social credit system in October 2011. The system is still in the early stages of implementation.

At its core, China’s social credit system is a set of databases managed by China’s economic planner, the National Development and Reform Commission, and by the People’s Bank of China, and supported by the country’s court system.

The system gives a score for both individuals and companies after collecting, aggregating and analysing data from different sources, which include financial, criminal and governmental records, online credit platforms and video surveillance data.

The combination of surveillance technology and expansive governmental powers under the social credit system gives China the ability to correct a citizen’s behaviour almost instantly, once it is deemed incompatible with the social credit system, Zhou said.

“Everyone is like a rat in a cage in such a society. Many aspects of the rat’s nature can be altered by monitoring and simultaneously correcting them,” Zhou added, referring to one of the possible effects on residents of living in a tightly monitored society.