Tong Ying-kit is accused of riding a motorcycle into police officers during a July 1 protest last year, but legal experts say he faces uphill battle in light of Court of Final Appeal’s ruling in Jimmy Lai case.

The first person charged under Hong Kong’s national security law may challenge prosecutors’ decision to remove jurors from his trial, but is expected to face an uphill battle following the top court’s latest ruling on its jurisdiction.

Tong Ying-kit, who is accused of riding a motorcycle into police officers during a July 1 protest last year, is exploring the possibility of challenging the decision for him to be tried by three High Court judges designated by the city’s leader under the Beijing-imposed legislation, according to a legal source.

The lawyer also confirmed that Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah’s decision was tied to concerns about the safety of jurors and their family, as well as the real risk the administration of justice might be impaired.

Officials, citing ongoing proceedings, have sidestepped questions about the reasons for invoking the legislation’s provision to hold a trial by judges, instead of in front of a jury, in the present case over charges of inciting secession and terrorism.

The jury-free arrangement was among the legislation’s provisions attracting a cascade of criticism from legal experts when the law came into force last June – and some believe it can be challenged through a judicial review.

But the Post has been told any potential applications would not be lodged soon, in light of further developments at the Court of Final Appeal, which on Tuesday answered a key question on the extent of the city courts’ powers of constitutional review in connection with the new law.

The top court, in setting aside media tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying’s bail, said the legislative acts of the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee leading to the promulgation of the national security law were in line with the provisions of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

“We have decided that there is no power to hold any provision of the [national security law] to be unconstitutional or invalid as incompatible with the Basic Law and Bill of Rights,” the court said.

Professor Simon Young Ngai-man, associate law dean of the University of Hong Kong (HKU), who believed it was possible to judicially review Cheng’s decision, said the ruling meant it cannot be argued that Article 46 was incompatible with the Basic Law.

Article 46 is the security law provision that stipulates the secretary for justice has the power to issue a certificate directing the replacement of a jury with a three-judge panel.

“It can be argued that the decision was unlawful on traditional public law grounds,” Young said, referring to principles of illegality, irrationality and procedural unfairness.

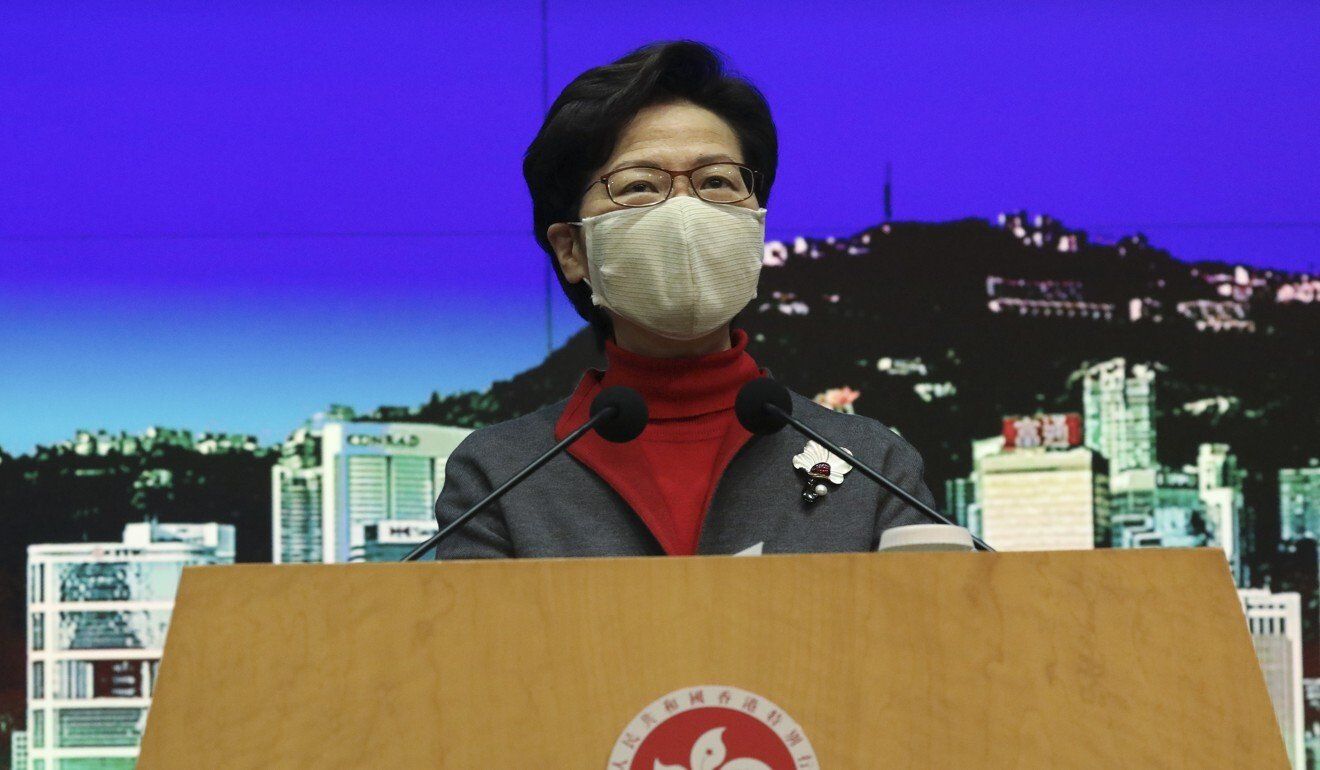

Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam did not comment directly on the case.

Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam did not comment directly on the case.

Young observed there was “probably a reasonable basis” for the decision, as there would be many important legal questions that needed to be resolved and “it is best to do that with three judges rather than with a single judge and a jury”.

But the professor added: “I fear this decision may be setting the bar too low and will serve as a precedent to remove the jury in all serious national security law cases.”

Veteran criminal lawyer Stephen Hung Wan-shun said it was within the prosecution’s prerogative to make the decision – such as deciding a defendant’s venue of trial – given that discretion was expressly stipulated in the legislation.

Hung also noted the same provision did not expressly state that the secretary’s decision would be final and could not be challenged, which, in theory, meant it could be subject to judicial review.

But he believed applicants would face many hurdles in an “uphill battle” because of that prerogative, and the need to explain why prosecutors’ concerns were entirely unreasonable.

Former top prosecutor Grenville Cross similarly observed that it would be necessary for applicants to show there was no proper basis for the decision.

“Since this decision is one which [Cheng] can lawfully make, an aggrieved party would have to point to perversity on her part,” he said.

On the other hand, if the decision was made in accordance with risk assessment conducted by police, the prospect of success would be minimal as Cheng had a duty to protect jurors.

“Had she not acted as she did, and people were subsequently harmed, the repercussions would have been considerable,” Cross said.

Eric Cheung Tat-ming, another legal scholar from HKU, said Cheng’s decision was expected as soon as the provision was included in the new law, but questioned her reasons, when there was no evidence of any potential threat to jurors.

“Why is it that they can ensure the judges’ safety but not the jurors’?” he said.

The principal lecturer said the jury system was introduced as a safeguard to check against bad law, and Cheng’s decision to “circumvent and damage the system” had resulted in the natural consequence of giving the impression the government did not trust juries.

When asked to address this impression, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor declined to comment on individual cases, citing the ongoing judicial process.

But she added: “This is a piece of national legislation and Hong Kong is the primary authority for implementing [it].

“That is already a very strong indication of trust – trust in ‘one country, two systems’, trust in the Hong Kong systems, whether it is executive or judicial.”

The department has similarly declined to comment.