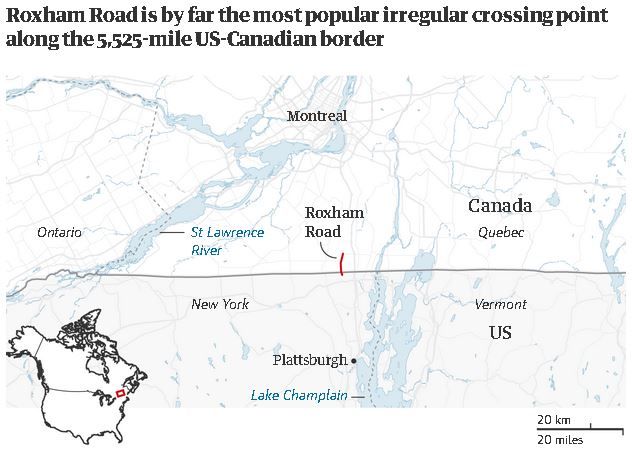

Roxham Road, linking New York state and Quebec, is by far the busiest crossing for asylum seekers, thanks to a legal ‘loophole’

Mohammed Al-Hashemi had been in the United States for two months when his phone rang. There was no caller ID. “I can take you straight to Canada,” said the man, before warning: “It may cost you a lot of money.”

“I told him, ‘OK.’ I was ready to go, ready to move to the next step,” said Al-Hashemi, who had been a lawyer in Yemen before he was forced to flee.

He was driven the next day to Roxham Road, which runs between Quebec and Plattsburgh, New York. After walking across the border, Al-Hashemi made his way to Montreal, where he stayed at a refugee shelter until his asylum claim was accepted.

Since 2017, more than 60,000 asylum seekers have entered Canada through such irregular routes from the US, due to what some have called a “loophole” in a treaty between the two countries. The Safe Third Country Agreement, which has been in effect since 2004, stipulates that asylum seekers in either country must seek refugee protection in whichever country they first arrive and will be turned away from ports of entry to the other nation.

But this agreement doesn’t apply to irregular crossings. And along the 5,525-mile border, Roxham Road is by far the most popular irregular crossing point. In the first three months of 2022, Royal Canadian Mounted Police intercepted more than 7,000 asylum seekers crossing into Quebec, primarily at Roxham Road.

This influx is causing growing friction between provincial and federal authorities, prompting Quebec’s premier, François Legault, this month to ask Canada’s government to shut down Roxham Road, arguing that the province doesn’t have the funds or housing to handle the number of asylum seekers seen in recent months.

Refugee advocates disagree with those claims. “The refugee organizations in Montreal have said very clearly that they do have capacity,” said Wendy Ayotte, founder of the Quebec-based group Bridges Not Borders, who argued that without the reliable route of Roxham Road, asylum seekers would resort to more dangerous options. “A definitive closure will be a major driver for smuggling,” said Ayotte.

Asylum seekers cross into Canada from the US border near a checkpoint on Roxham Road near Hemmingford, Quebec, last month.

Asylum seekers cross into Canada from the US border near a checkpoint on Roxham Road near Hemmingford, Quebec, last month.

Although it is not an official port of entry, the crossing at Roxham Road is overseen by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and adheres to a clearly established system.

Day and night, taxis drop off asylum seekers. Some have just arrived in the United States on a visitor visa, others have been living there for years. Cab drivers yell out “French!” or “English!” to police waiting on the Quebec side. As people approach the border, they are arrested, read their rights and taken to shelters in Montreal.

Closing Roxham Road would exacerbate smuggling that already occurs along the border, said Craig Damian Smith, a senior research associate at Toronto Metropolitan University. He added that most asylum seekers using smugglers have already had an asylum claim rejected in the US – or are undocumented.

Ali, who requested his real name not be used, is a small business owner who fled from Yemen to escape the lawlessness and violence of the country’s brutal civil war. For the past seven years, he has lived in Buffalo, New York, waiting for the resolution of his asylum claim, but his patience is running out. “If nothing is new for me in a couple of months, I’m going to try to go [to Canada],” he said.

Smugglers in Buffalo offer transportation to Roxham Road for $1,000-$2,000 per person. To avoid raising police suspicion, they pose as Uber or Lyft drivers by placing company stickers on their windshields. Ali initially contemplated hiring a smuggler before realizing he could just take a bus to Plattsburgh.

The existence of smugglers is common knowledge among Roxham Road’s taxi drivers working Plattsburgh’s bus stop. Cab drivers also meet with “runners”, who charge refugees large sums to be driven to Plattsburgh from all over the country, said local cab driver Wayne, who asked that his full name not be used.

While most irregular crossings occur at Roxham Road, some asylum seekers take more dangerous routes. Seidu Mohammed feared persecution in his native Ghana for being bisexual., and in December 2016, he traveled to Manitoba on a journey that almost cost him his life.

Mohammed and a companion found a driver in Minnesota willing to take them to the border for $200 each. After crossing into Manitoba, they walked for hours in the snow before flagging down a truck. Both men lost their fingers to frostbite.

Mohammed’s asylum claim was accepted, and he has since founded a soccer program for underprivileged families and new refugees in Canada.

At the time of his crossing, he was unaware that Roxham Road existed. “If I’d known, I would’ve gone there instead.”

While Quebec is concerned with the closure of Roxham Road, the legal framework of migration may soon be changing. Justin Trudeau has repeatedly said that Canada is negotiating a new version of the Safe Third Country Agreement with the United States. La Presse reported in December that these negotiations will close the “loophole” and halt irregular migration across the border.

Police in Quebec intercepted more than 7,000 asylum seekers in the first three months of 2022, most of them on Roxham Road.

Police in Quebec intercepted more than 7,000 asylum seekers in the first three months of 2022, most of them on Roxham Road.

How and when any amendments will take shape remains unclear. However, like the closure of Roxham Road, it’s speculated that an expanded agreement would affect smuggling.

“With an expansion of that sort, the smuggling would be even more intense and dangerous and costly,” said Janet Dench, executive director of the Canadian Council for Refugees.

Neela Hassan, 29, left Afghanistan in 2019, after her research on female education led to threats from the Taliban. Hassan took immigration classes, spoke with lawyers, and memorized her rights as an asylum seeker. Then, she flew to Plattsburgh and took a cab up to Roxham Road.

If the crossing hadn’t been accepting asylum seekers at the time, Hassan believes she would have resorted to using a smuggler.

“It’s hard to understand why someone would take a dangerous step like that. But sometimes you’re in a very desperate situation where you’re like, do it or die,” said Hassan.

“You take the risk because your life is at risk.”