Minister says inciting voters to leave ballot papers blank could violate Basic Law, but analysts warn banning the practice could hamper turnout, raise legitimacy questions.

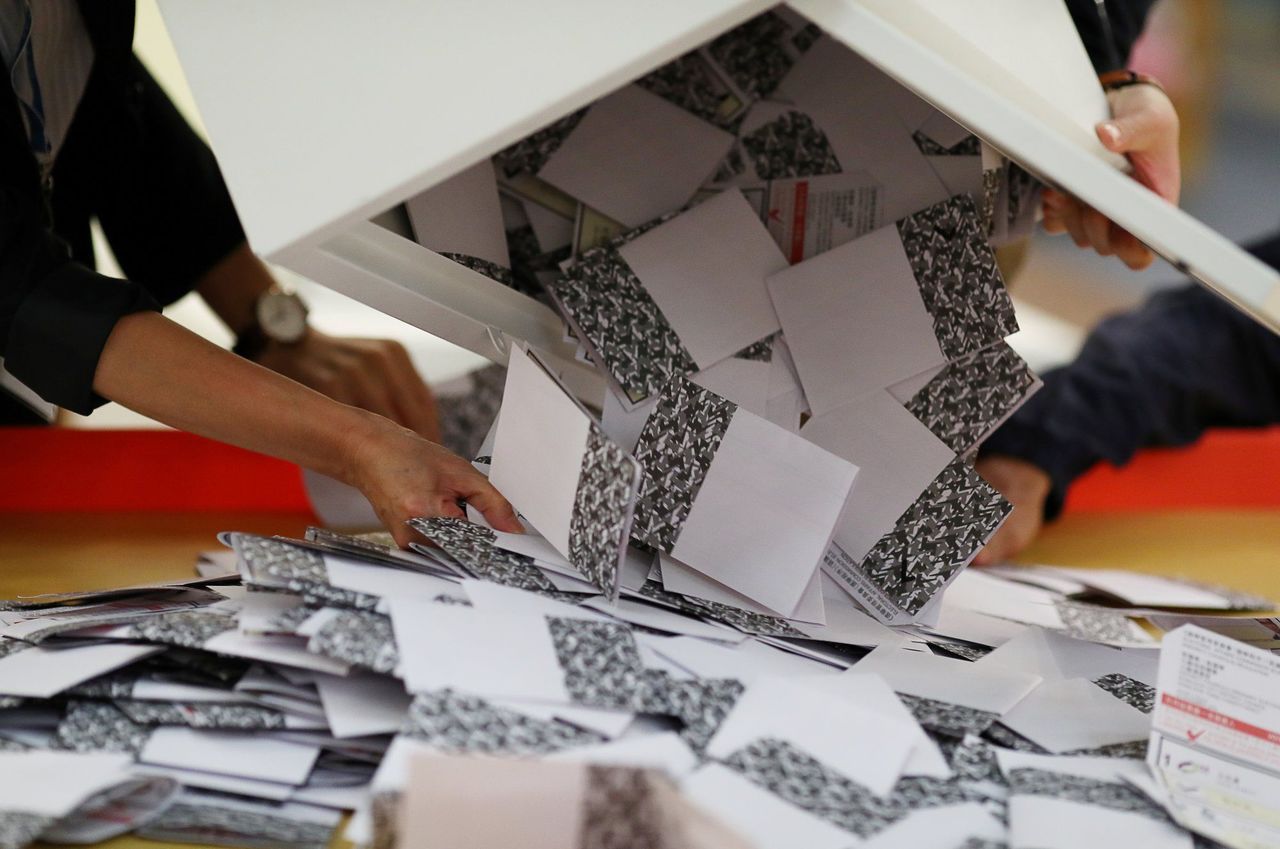

Three elections coming up in Hong Kong will play out in a dramatically reshaped political landscape following Beijing’s sweeping overhaul of the city’s electoral system, and there have already been calls for voters to protest by casting blank ballots.

So much will be different, from an expanded Legislative Council to an enlarged Election Committee with wider powers, as well as the potential disqualification of opposition candidates deemed not patriotic enough to run.

Top officials hit a raw nerve with observers and the opposition by warning that the authorities could outlaw attempts to encourage protest votes in the coming elections.

Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Erick Tsang Kwok-wai declared last week that “encouraging, organising or inciting” others to cast blank votes could be seen as manipulating elections, a possible violation of Annex I of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

Analysts warned that imposing a ban could prove embarrassing to the government, as it could result in a lower voter turnout and put the legitimacy of local elections in further doubt.

Pro-establishment heavyweights such as constitutional law expert and former Basic Law Committee member Albert Chen Hung-yee believe it is in Hong Kong’s best interests to refrain from criminalising calls for blank votes.

Emily Lau Wai-hing, former chairwoman of the opposition Democratic Party, said if a ban came to pass, voters would just resort to other “creative ways” to protest against Beijing’s overhaul of the electoral system.

“The authorities should look for remedies to encourage voting, instead of intimidating people to cast ballots,” she said.

Top officials hit a raw nerve with observers and the opposition by

warning that the authorities could outlaw attempts to encourage protest

votes in the coming elections.

Top officials hit a raw nerve with observers and the opposition by

warning that the authorities could outlaw attempts to encourage protest

votes in the coming elections.

A government source said the feasibility of imposing a ban would need to be studied, as it did not exist in most places in the world.

“What’s certain now is that it’s nearly impossible to outlaw blank ballots, because voters’ choices have to remain secret,” the source said.

‘Best to maintain the status quo’

Invalid votes are known in elections everywhere, either as a result of voters deliberately leaving their ballots blank or spoiling them as a sign of protest, or when they make mistakes while marking them.

In Hong Kong, campaigns to cast blank votes have not been uncommon in the relatively brief history of direct elections since 1991, before the British returned the colony to China in 1997.

Figures from the city’s electoral office show that invalid votes in Legco elections since the handover ranged from 0.57 to 1.52 per cent of total votes cast. These included ballots which were left blank or where the voters chose more than one candidate.

The authorities have never distinguished between ballots spoiled deliberately and those where the voters made a mistake. Overall, the proportion of invalid votes has been insignificant compared with many other places.

According to data compiled by Sweden’s International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, or International IDEA, invalid votes in the most recent parliamentary elections in Indonesia, the Philippines and Iraq made up more than 13 per cent of total votes cast.

The 2017 French presidential election won by Emmanuel Macron saw the highest level of protest votes in half a century, with four million voters – 11.5 per cent of the total – casting blank or spoiled ballots to indicate they wanted neither centrist nor far-right candidates.

Hong Kong voters do not have the option of indicating “none of the above”, a practice prevalent in some countries including India.

In 2012, more than 60,000 voters, or 3.59 per cent of the total, opted to leave their ballots blank and chose none of the candidates in the new five Legco “super seats” created as a result of negotiations between some in the pan-democratic camp and Beijing. The boycott came as a result of a two-week campaign led by People Power, a radical party of the pan-democratic camp, to protest against what it criticised as secret negotiations with Beijing.

The same year, the Civic Party urged members of the Election Committee to cast blank votes in protest against the “small circle” choosing the city’s leader. Invalid votes accounted for 7 per cent of the total that year, significantly higher than the 2 per cent in the previous election in 2007.

In 2014, pro-establishment heavyweight Albert Chen proposed adding “none of the above” on ballots for choosing the chief executive. He suggested that an election would be ruled invalid if more than half the votes chose none of the candidates.

The idea was rejected by city officials who were concerned it would give rise to legal controversies.

Chen, a law professor at the University of Hong Kong, told the Post it would be in Hong Kong’s best interests not to criminalise calls for voters to cast blank votes.

“Under the existing law, it is not unlawful not to vote or to cast a blank vote, and advocating such behaviour is not a criminal offence,” he said. “I think this legal position should be maintained.”

But he noted that with current moves to ensure that Hong Kong public office holders swear allegiance to the city and the Basic Law, it might be possible that anyone who advocates spoiling votes could be considered disloyal, leading to disqualifications.

Turnout an indicator of voters’ mood

Voters also show how they feel about elections by showing up in large numbers to vote or staying home, and this is reflected in the overall turnout.

Former transport and housing minister Anthony Cheung Bing-leung said outlawing campaigns for blank votes would do nothing to boost the turnout for the Legco elections in December because it would be difficult to implement the law.

Legco has been expanded from 70 to 90 seats and under recent changes, the number of directly elected seats has been reduced from 35 to 20.

The Legco polls will be the first since November 2019, when opposition

candidates scored a landslide victory in district council elections.

The Legco polls will be the first since November 2019, when opposition

candidates scored a landslide victory in district council elections.

The year-end polls will be the first since November 2019, when opposition candidates scored a landslide victory in district council elections held in the midst of anti-government protests. The turnout was a record 71 per cent of the electorate.

Cheung, a political scientist, said it was too early to forecast the turnout for this year’s Legco polls, but the agendas put forward by candidates would be a determining factor in mobilising voters.

“If some voters believe their votes cannot make a difference, their incentive to go to the polling stations will be dampened,” he said. “The Hong Kong government and Beijing will be embarrassed if the turnout for the coming Legco elections is significantly lower than in 2016.”

The 2016 Legco elections saw a turnout of 58 per cent. The 2.2 million people who voted marked the highest turnout for Legco elections. That year’s election was also the first after the pro-democracy Occupy protests of 2014.

Cheung said the turnout in Hong Kong elections tended to be influenced by prevailing social sentiment.

He said the turnout for the first post-handover Legco elections in 1998 surged to 53.29 per cent because the tenure of the controversial provisional legislature set up before the handover had ended, while pan-democrats who boycotted what they called an undemocratic body staged a comeback.

The turnout for the 2000 Legco election dropped to 43.57 per cent, before rising sharply to 55.64 per cent in 2004 – a year after 500,000 Hongkongers took to the streets to protest against a national security bill that was ultimately shelved.

Ivan Choy Chi-keung, a political scientist at Chinese University, noted that the record turnout for the 2016 Legco elections was boosted by first-time voters aged 18 to 20 who came out in large numbers following the Occupy protests that shut down parts of the city for 79 days.

He expects the turnout of young voters to drop significantly in December, given the dampening effect of Beijing’s overhaul of the electoral system.

Choy, who has been studying voting behaviour in Hong Kong since the 1990s, said a crucial sign was whether this year’s turnout would sink as low as the 35.79 per cent recorded in the 1995 Legco elections.

“The Hong Kong government will be very embarrassed if the December election scores that record low turnout,” he said. “But it won’t cause too much damage to the government, as it seems it no longer cares about public opinion.”