Relations with its continental neighbors are destined to shape the U.K. for many years to come.

The memorial to the Gatow air disaster of 1948 is easy to overlook in a city with more than its fair share of 20th century ghosts. A simple plaque in Berlin’s Westend district commemorates the mid-air crash that claimed the lives of 15 people during the early days of the Cold War.

The stone inscription may be inconspicuous, but its location in St. George’s Anglican Church reflects a long-standing British presence in the German capital, and the events it marks are a window onto the U.K.’s pivotal role in shaping the postwar European order.

With Brexit now real, the U.K. may discover that it’s not so simple to shed a European identity so anchored in history and geography. Indeed, that reality—and a political culture perennially dogged by questions over the relationship with its European neighbors—seem destined to bind Britain to the continent for years to come, for all the government’s efforts to rebrand the nation as the globe-trotting champion of international free trade.

After striking a trade deal with the European Union on Christmas Eve, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it was time to move on. The U.K. must leave “old, desiccated, tired, super-masticated arguments behind” and “keep Brexit done,” he told the House of Commons on Dec. 30 as he rushed the accord into law.

Given Britain’s postwar history, that finality may be wishful thinking. Indeed, the pro-Brexit camp has been guilty of playing down the European dimension of the country’s past, according to Helene von Bismarck, a historian of Britain’s role in 20th century international relations.

It presents “a highly selective view of British history,” she said. “This whole idea that now we’re free to return to who we really are—history really doesn’t substantiate that.”

Britain’s role in postwar Germany affords a sense of the extent of those continental ties. Berlin in 1948 was a city on edge when, in April, a Vickers aircraft from London via Hamburg was involved in a collision with a Soviet Yak fighter on its approach to the British airfield at RAF Gatow, killing all 14 passengers and crew as well as the Soviet pilot. Each side blamed the other for an international incident that contributed to the rapid deterioration of east-west relations.

Within two months, London was the setting for a declaration of allied plans to create a West German state, enraging Soviet leader Josef Stalin, who ordered Berlin be cut off from the rest of Germany. It was Britain’s foreign minister, Ernest Bevin, who convinced the Americans to take the lead in airlifting in supplies and breaking the blockade, historian Tony Judt wrote in his 2005 book, “Postwar.” The continent would be divided until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Washington and Moscow may have been the key Cold War actors, but Britain was at the heart of the events that forged the new European reality—even if it wouldn’t be until the 1970s that the U.K. hitched its fate to that of the continent by joining the forerunner of the region’s defining political project, the EU.

In February last year, days after the U.K. made good on the 2016 referendum result and officially left the EU, Johnson used a speech on Britain’s post-Brexit future to say that the U.K. was “re-emerging after decades of hibernation” and ready to resume its historic role as the world’s leading advocate of free trade.

Recent research by the European Council on Foreign Relations suggests the U.K. won’t be able to airbrush Europe out so easily. A majority of U.K. policy experts from government, think tanks, academia and the private sector see the country’s future role in global politics as one of close association with the EU, a study by the think tank found. Leading a “resurgent Commonwealth” of nations was seen as the least realistic outcome, favored by less than 2% of those polled.

While the Brexit deal sealed on Dec. 24 delineates the extent of future ties, the study shows there’s scope for a return to closer collaboration—especially in fields including climate change, EU-U.K. migration and foreign policy—if London chooses.

Both sides had better not leave it too late. A parallel study found Ireland to be the only one of the EU’s 27 members that saw U.K. relations as a top priority. Overall, the U.K. ranked less of a priority for the bloc’s members than China, Russia, the U.S.—or even the western Balkans.

“There is a certain fatigue and I think that has an effect on the readiness to engage,” said Jana Puglierin, head of the ECFR’s Berlin office and director of the research project. “Those states that have been traditionally close to the U.K. have moved on.”

That’s unlikely to be a luxury afforded the U.K., which has been traumatized by questions of European integration since the war. As far back as 1950, when plans for the European Coal and Steel Community were floated, Britain refused to take part due to suspicion of continental influence in its affairs.

It was also an economic decision: In 1947, the British economy looked in far better health than those of its neighbors, helped by trade with the empire. But by the end of 1951, West German exports were fueling a “European economic renaissance,” historian Judt wrote.

By 1955, Britain had signed an association agreement, and in 1961 it applied to become a full member of what was then the European Economic Community—its application famously vetoed by French President Charles de Gaulle.

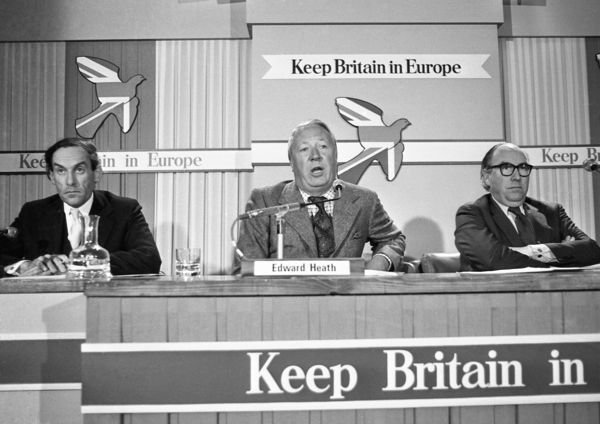

The U.K. under the Conservative government of Edward Heath was finally admitted to the EEC on Jan. 1, 1973. But what followed was 47 years of on-off wrangling that ultimately led to the U.K.’s EU exit on Jan. 31.

Accession was quickly followed by a referendum on membership called by a Labour government dogged by party infighting over Europe. In the 1980s, the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher turned increasingly euroskeptic and Europe played a major role in her downfall in 1990. Her successor, John Major, struggled for control of his cabinet on the issue throughout his time at No. 10 Downing Street.

Prime Minister David Cameron sought to lance the boil by granting another referendum on EU membership. The vote to leave cost him his job and that of his successor, Theresa May.

All that controversy is “receding in the past behind us,” Johnson said in February. “We have the opportunity, we have the newly recaptured powers, we know where we want to go, and that is out into the world,” he said. His aim is to a forge a “Global Britain.”

The U.K.’s dilemma is that it risks being on the wrong side of history by going it alone at a time of great power rivalry between the U.S. and China that is unlikely to change under a Joe Biden administration.

Turning its back on a half-century economic and political alliance with Europe looks increasingly risky, especially as Brexit-supporting President Donald Trump exits the White House and Commonwealth countries Australia and India are banding together with Japan to better fend off the challenge from China.

The EU, meanwhile, has its own challenges around leadership, according to Matthew Goodwin, professor of politics and international relations at the University of Kent in England. With the U.K. prerogative now to forge trade agreements with non-EU partners, the two sides “will move increasingly in different directions,” he told Bloomberg Television.

History suggests those paths are destined to converge again, however. Even Johnson acknowledges that the U.K. is a European power “by irrevocable facts of history and geography and language and culture and instinct and sentiment,” just not “by treaty or law.”

Back in 1948, Prime Minister Clement Attlee’s Labour government faced a historic decision over the country’s future ties with the continent, and opted to break with previous British thinking in favor of allying with Europe.

Again it was Bevin, his foreign minister, who committed the country to “engagement with her continental neighbors in a common defense strategy, a ‘Western European Union,’ on the grounds that British security needs were no longer separable from those of the continent,” Judt wrote.

That union became the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, signed into being in April 1949 by the U.S., Canada and 10 European nations, and still the bedrock of transatlantic relations today.

The following year, the foundation stone for St. George’s Church was laid in the British sector of Berlin, replacing an older English chapel that was destroyed in a wartime bombing raid. The plaque for the victims of Gatow was added later.

For Puglierin at the European Council on Foreign Relations, policy areas of mutual interest hold out the promise of future U.K.-EU cooperation, despite the current British government’s desire to cut loose. “Not everything is lost,” she said.