Contributor Choy Yuk-ling, who helped produce episode of Hong Kong Connection on last year’s July 21 incident, arrested on suspicion of violating the Road Traffic Ordinance.

Police set off a storm among media organisations on Tuesday by arresting a reporter with Hong Kong’s public broadcaster over a programme about a mob attack at Yuen Long railway station, one of the most controversial and divisive chapters in last year’s anti-government protests.

RTHK contributor Bao Choy Yuk-ling, who co-produced an episode of the television show Hong Kong Connection on the July 21 incident, was arrested on suspicion of making a false declaration when searching for personal details of car owners in the government database.

She was accused of violating the Road Traffic Ordinance by using the information she obtained for a purpose other than what she had stated when applying for access.

A police source said the investigation was prompted by a complaint from a member of the public and a referral from the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data.

Choy was released on bail in the evening after being charged with two counts of making false statements under the Road Traffic Ordinance.

Her case will be mentioned at Fanling Court next Tuesday.

Choy’s arrest triggered immediate alarm and condemnation among journalist groups, scholars and opposition politicians, who accused police of using the law to suppress regular reporting activities and creating a chilling effect on investigative journalism.

“Choy conducted searches in the interests of the public. The high-profile arrest is a clear warning from the government that journalists should stop doing something similar,” said Professor Clement So York-kee, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s journalism school.

As the head of RTHK, director of broadcasting Leung Ka-wing said: “We are afraid, we are worried, whether we can continue producing accurate news the way we did before.”

After her release, Choy said her arrest would affect how journalists gathered news in the future.

“Unfortunately, with police using the July 21 report as a reason or backdrop to arrest a journalist, I fear it has already created worry among the public who may suspect police are using this to suppress freedom of the press or even cause a chilling effect,” she said.

“I hope news workers in Hong Kong can continue to uphold their values, be unflinching, fearless and impartial.”

Choy was arrested during a raid on her Kwai Chung home by officers from the New Territories North regional crime unit on Tuesday afternoon.

She had sought to access what is officially known as the Certificate of Particulars of Motor Vehicle through the Transport Department website in May and June, which would allow her to obtain personal details of related car owners such as their names, addresses and identity card numbers.

Under the Road Traffic Ordinance, a person is liable to a fine of HK$5,000 (US$641) and six months’ imprisonment if he or she knowingly makes a false statement when requesting such information.

Anyone who breaches the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance by causing “psychological harm” to someone from the disclosure of personal data without consent is also subject to a fine of HK$1 million and five years’ imprisonment.

While the privacy law exempts news coverage from criminal liability in such circumstances, the transport law provides no similar protection for journalists.

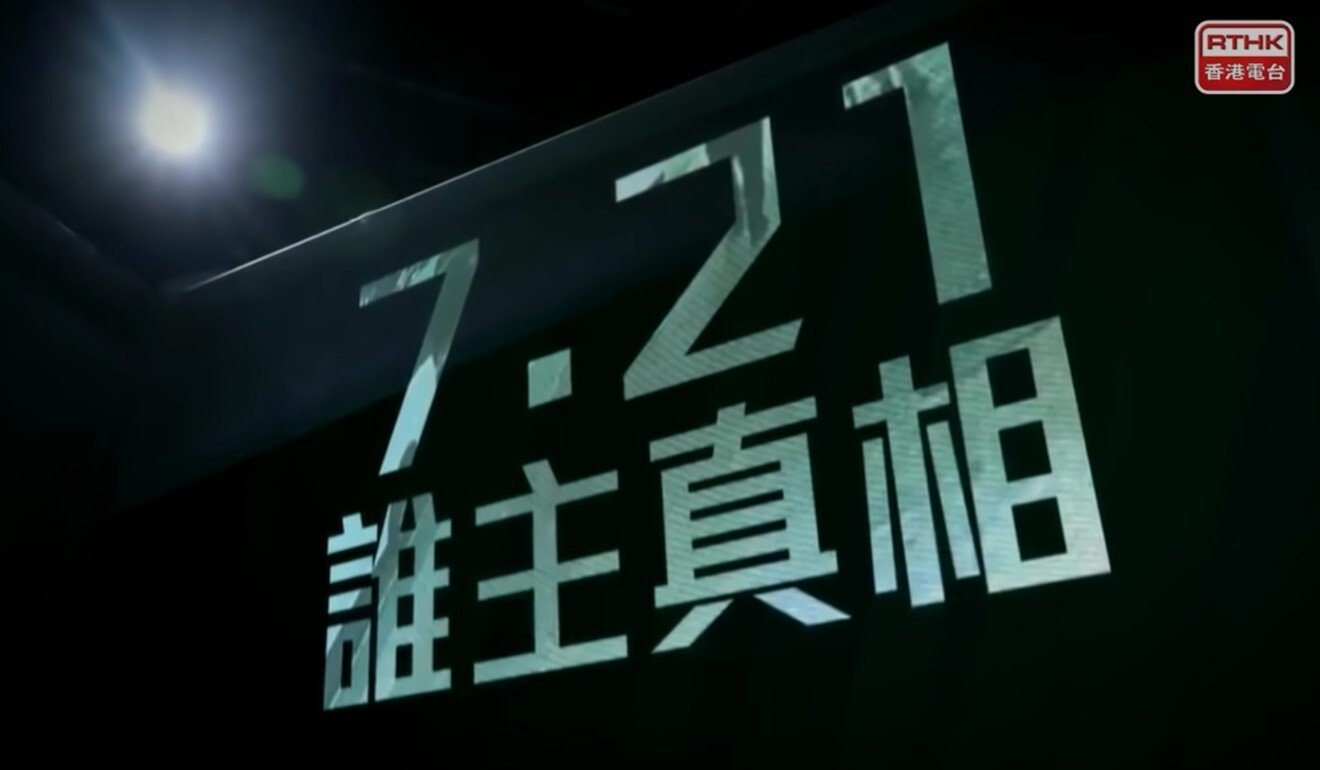

Choy, 37, was one of three producers of the show that was broadcast on July 13 this year titled 7.21: Who owns the truth to mark the first anniversary of the Yuen Long attack.

In what was widely seen as a turning point in last year’s social turmoil, a group of white-clad men indiscriminately attacked passengers and protesters returning from a mass rally.

The slow police response that night sparked a public outcry, with officers accused of colluding with the assailants – an allegation police have repeatedly denied.

The 30-minute programme sought to identify those wearing white by reviewing CCTV footage obtained from nearby shops and videos posted online.

Searches were also conducted through the government website to identify the owners of cars in the vicinity captured on video, which were said to have picked up some of the attackers that night.

The RTHK report claimed that some of the car owners were village heads from the neighbourhood, but most of the motorists it identified could not be reached for comment on the show.

It has been a common practice for the city’s journalists to search for information on vehicle, land and company ownership through the government’s online platforms for investigative reporting.

In an older version of the Transport Department’s application form still available in December, a space was provided for members of the public to state their exact purpose for requesting car owners’ personal data. But that option was removed in the updated version now available online, which only provides for applicants to check boxes citing “legal proceedings”, “sale and purchase of vehicles” and “other traffic and transport related matters” as the purpose.

The new version also requires applicants to declare that they will only use the personal data collected “for activities relating to traffic and transport matters”.

Chinese University academic So said the “unreasonable modification” had exposed journalists to legal risks.

A quarter of vehicle licence plate searches made in 2010 were by media organisations.

From 2016, the Companies Registry – another investigative tool commonly used by journalists – also started to require users seeking particulars of registered companies or their directors to declare a reason for doing so, but without providing “news reporting” as an option. The arrangement sparked concerns at the time about curbing corporate transparency, and the registry later clarified that one of the options could cover the collection of information for the purpose of news reporting activities.

Every government department allows members of the public to seek information relating to its policies and services through an access-to-information code, but that does not include confidential personal data.

Barrister Duncan Ho Dik-hong noted that the Road Traffic Ordinance did not provide a defence for journalists making false declarations. If the information obtained was knowingly used for reporting – a purpose not stated among the three options available in the declaration form – he or she could be held liable.

Professor Simon Young Ngai-man, a legal scholar from the University of Hong Kong, said the application form itself was at fault if it did not fairly allow Choy to indicate her true purpose or the public interest involved.

“It may be doubtful whether her ticking of one of the limited number of boxes was dishonest or misleading,” he said.

To seek redress, Ho said, journalists would have to appeal to the transport commissioner. Failing that, they could mount a legal challenge, which would be a convoluted process with no guarantee of winning.

In a joint statement led by the Hong Kong Journalists Association, eight media groups and unions demanded Choy’s immediate and unconditional release, and an explanation from police to justify their action.

“The police’s abuse of the Road Traffic Ordinance has suppressed normal reporting activities and is bound to erode freedom of the press,” it read.

The Hong Kong News Executives’ Association expressed strong concerns over the arrest, urging police to respect press freedom and the public’s right to information.

RTHK, the producer of many in-depth documentaries and political satire shows critical of the government, has been the target of the authorities and pro-establishment groups who accused its journalists of being biased in support of last year’s protest movement.

Earlier this year, an episode of the now-suspended political satire show Headliner, which had mocked the city’s police force, prompted the Commerce and Economic Development Bureau to order RTHK to take disciplinary action against staff responsible.

The privacy commissioner’s office refused to comment.