There would have been little point in a Surrealist exhibition with all the sexual references removed. There is, thankfully, no fig leaf at the Hong Kong Museum of Art. Yet, there are some stunning omissions.

The Surrealism exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art has long queues, and rightly so. “Mythologies: Surrealism and Beyond” has over a hundred pieces of art and archive material on loan from the Centre Pompidou in Paris, including major paintings and sculptures by Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Joan Miró and Alberto Giacometti.

The curators have traced the fascinating developments of Surrealism since André Breton’s 1924 founding manifesto to convincingly demonstrate that after the first world war, there appeared an urgent and radical impulse to subvert existing cultural hierarchies, to unearth the root of desires and beliefs, and expose the lie of a rational, orderly world.

Hence the title of the exhibition. That diverse cohort of artists from nearly a century ago are celebrated for having the intellectual mettle to reconfigure and deface old myths, to make the familiar intensely disturbing.

A lot of the visual imagery here is sexual. These artists were active during the immediate decades after Sigmund Freud published his Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and proposed the idea of the Oedipus complex. Dalí’s William Tell (1930) is laden with castration anxiety: the Swiss folk hero is looking at his fleeing, fig-leaved son menacingly, scissors in hand and his manhood on proud display.

The classical myth of Minotaur became, for the Surrealists, a symbol of irrational urges driven by passion and emotion, and the monstrous bovine makes numerous appearances in the works included in that section of the exhibition, such as an abstract childlike doodle with sharp teeth and pronounced sexual organs in Miró’s The Bull Fight (1945).

Another segment is titled Acephale, a headless figure symbolising a Surrealist myth fabricated by the French philosopher George Bataille. All body and no brain, this complex symbol is shown to have inspired Giacometti’s sculpture of a crushed praying mantis, shockingly titled Woman with Her Throat Cut (1932/1940). Nearby, Magritte’s nightmarish The Rape (1945) is a portrait of a blonde woman, her facial features replaced by a naked female torso.

There would have been little point in a Surrealist exhibition with all the sexual references removed. There is, thankfully, no fig leaf here. And that should not be taken for granted today. The museum has been known to prevent younger people from seeing works with less explicit sexual imagery.

And earlier this year, pro-establishment critics of M+ wanted “immoral” and “vulgar” artworks removed from the museum collection, along with Ai Weiwei’s works or anything deemed anti-China.

In the West, curators are under more pressure not to offend. Rather than instigate intelligent debate on gender and sexuality with Giacometti’s splayed insect and Magritte’s objectified female, curators could have simply not shown them for fear of being on the wrong side of public opinion.

Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture of a crushed praying mantis, titled

“Woman with Her Throat Cut” (1932/1940), is one of the Surrealist pieces

on show at Hong Kong Museum of Art.

Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture of a crushed praying mantis, titled

“Woman with Her Throat Cut” (1932/1940), is one of the Surrealist pieces

on show at Hong Kong Museum of Art.

But a refusal to compromise does not have to be the same as being tone-deaf. And the exhibition is much diminished for some stunning omissions.

Just as Hong Kong is actively being “decolonised”, with remnants of Western imperialist superiority considered the height of political incorrectness, if not actually illegal, there is a cabinet of four sculptures made in present-day Gabon and Ivory Coast in the early 20th century. There is zero explanation given as to why they are here.

They are perhaps “surreal” in the general sense of the word: a ceremonial spoon from the Dan Yacouba tribe has two human legs. An ox mask by the Baoulé people is perhaps reminiscent of the Surrealists’ favourite half-man, half-cow being. But most of all, what comes across is the “primitiveness” of these anonymous African pieces.

About a century ago, Western artists such as Pablo Picasso first saw objects like these, often looted by colonisers, in their own museums and were so thrilled by these strange, exotic creations that they copied them in their own art. That was celebrated as pure genius for a long time but in recent decades, “primitivism” in Western art is also seen more critically, through the lens of cultural appropriation.

The concept of the primitive has been a major field of cultural studies for years, and it seems strange that an exhibition being brought from Paris to Hong Kong today would not be aware of a need to address this topic.

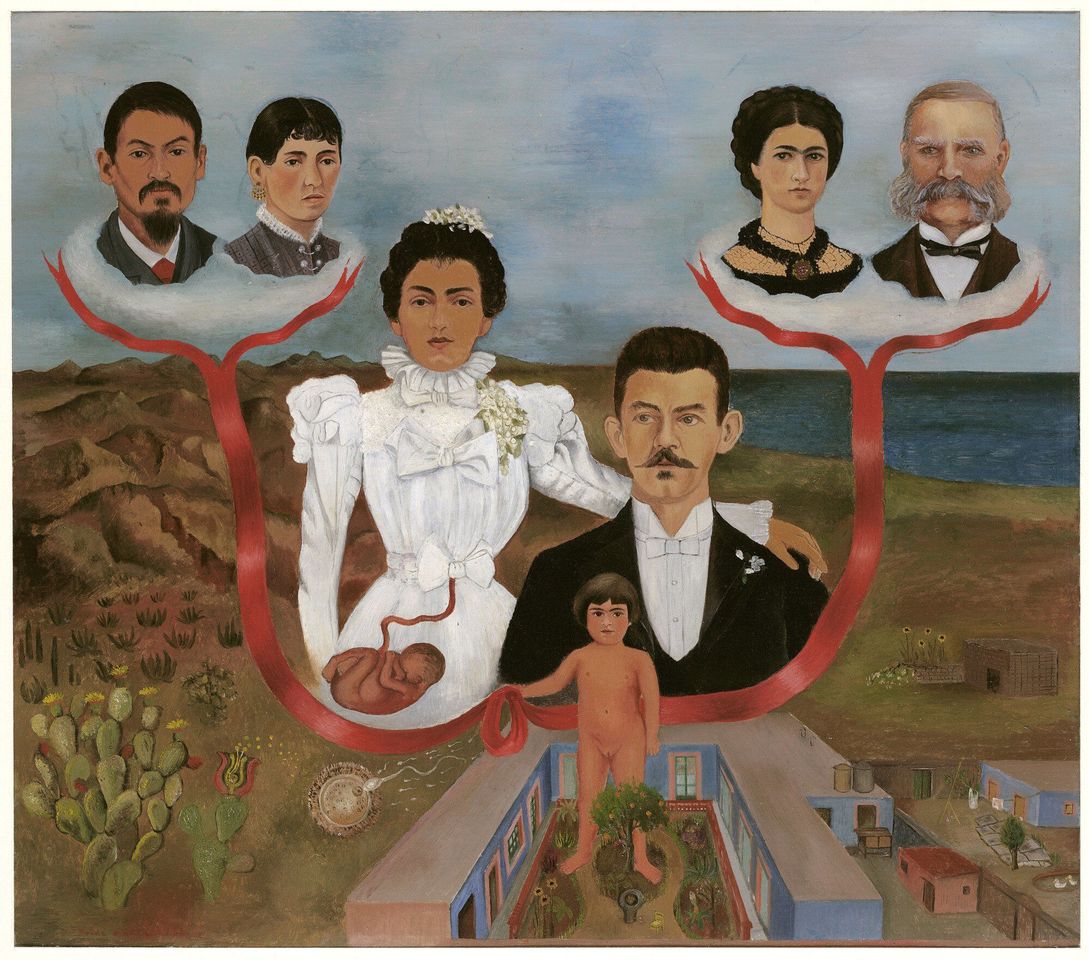

“My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree)”, 1936, by Frida

Kahlo. The prominent female artist could have been included in the

Surrealism exhibition.

“My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree)”, 1936, by Frida

Kahlo. The prominent female artist could have been included in the

Surrealism exhibition.

Also, there is no counterpoint to the heavily penile sensitivities here, an exhibition dominated as it is by the male artist’s use of the female body to portray his fears and desires. There are supposed to be three works (out of a hundred) by women in the main exhibition, but I did not come across them.

That is appalling. Some of the best-known female artists from the early 20th century could have been included: Frida Kahlo, Dorothea Tanning, Leonora Carrington. If I had not known better, I would have walked out of the museum thinking all successful Surrealists were men.

The exhibition is structured on “new myths” created by a generation of artists and thinkers. Strange, then, that it would perpetuate so many old myths that this generation now knows to be untrue.